Introduction: “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

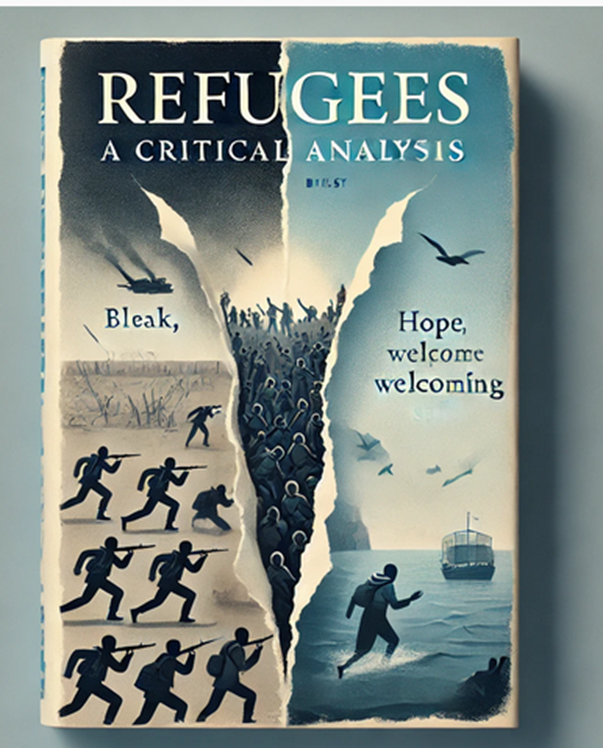

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston first appeared online on 23 March 2016, and was later included in his 2016 anthology You Took the Last Bus Home (published by Unbound), before being developed into an illustrated children’s picture-book edition. The poem’s core idea is that public speech about displaced people often swings between cruelty and compassion—and Bilston exposes that swing by making the same lines deliver two opposite arguments: read top-to-bottom, refugees are smeared as “Chancers and scroungers,” “Cut-throats and thieves,” who are “not / Welcome here,” and must “Go back to where they came from”; but the instruction “(now read from bottom to top)” flips the moral lens so the poem lands on shared humanity—“These haggard faces could belong to you or me”—and a call to solidarity (“Share our food / Share our homes / Share our countries”), rejecting the closed-border logic that “A place should only belong to those who are born there.” Its popularity comes from that instantly teachable “reverso” structure (a built-in twist that forces rereading), its blunt sampling of real-world xenophobic clichés, and its social-media friendliness—so a short poem becomes an argument you experience changing in your own mouth.

Text: “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

They have no need of our help

So do not tell me

These haggard faces could belong to you or me

Should life have dealt a different hand

We need to see them for who they really are

Chancers and scroungers

Layabouts and loungers

With bombs up their sleeves

Cut-throats and thieves

They are not

Welcome here

We should make them

Go back to where they came from

They cannot

Share our food

Share our homes

Share our countries

Instead let us

Build a wall to keep them out

It is not okay to say

These are people just like us

A place should only belong to those who are born there

Do not be so stupid to think that

The world can be looked at another way

(now read from bottom to top)

Annotations: “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

| Line | Text | Annotation | Devices |

| 1 | They have no need of our help | Opens with a blunt claim that denies responsibility and primes the reader for refusal. | 🟧 Loaded diction · 👥 Pronouns/ingroup-outgroup · 🟥 Irony (when reversed) |

| 2 | So do not tell me | A commanding interruption—shuts down empathy before it begins. | 📢 Imperative · 🎭 Direct address · 🟦 Enjambment |

| 3 | These haggard faces could belong to you or me | Brief flare of empathy: admits refugees are like us (this becomes central when reversed). | 🤝 Appeal to empathy · 🟪 Imagery (“haggard”) · 🟥 Irony/turning point (in reverse) |

| 4 | Should life have dealt a different hand | Uses fate/fortune to suggest anyone could be displaced. | 🎴 Metaphor/idiom (“dealt a hand”) · 🤝 Universalizing · 🟦 Enjambment |

| 5 | We need to see them for who they really are | Signals a coming “truth” but actually prepares prejudice and dehumanization. | 👥 “We” rhetoric · 🟧 Framing/loaded setup · 🟥 Irony (exposed in reverse) |

| 6 | Chancers and scroungers | Begins a list of insults to stigmatize and reduce complex lives to slurs. | 🟧 Loaded diction/slur · 🧱 Dehumanization · 🟨 Listing |

| 7 | Layabouts and loungers | Keeps the insult-list going; also musical sound-play to make hate memorable. | 🟨 Listing · 🟣 Alliteration (“l… l…”) · 🟧 Loaded diction |

| 8 | With bombs up their sleeves | Introduces fear: associates refugees with terrorism via a vivid (and unfair) image. | 💣 Violent imagery · 🟧 Stereotype/scapegoating · 🟥 Hyperbole |

| 9 | Cut-throats and thieves | Escalates to criminal labels; a moral panic move. | 🟧 Loaded diction · 🧱 Dehumanization · 🟨 Listing |

| 10 | They are not | A hard pivot; sets up exclusion (“not welcome”), but in reverse it becomes the start of a correction. | ⚖️ Antithesis setup · 🟦 Enjambment · 🔁 Reversal-function |

| 11 | Welcome here | The exclusion lands: “not welcome.” In reverse, “Welcome here” becomes the ethical headline. | 🚪 Exclusion/inclusion motif · ⚖️ Antithesis · 🔁 Reversal |

| 12 | We should make them | The phrase “make them” implies force/coercion—authoritarian tone. | 📢 Imperative/modal “should” · 🧭 Ethical pressure · 🟥 Irony (reversed) |

| 13 | Go back to where they came from | Classic nativist slogan; denies causes of flight and ignores danger. | 🧱 Othering · 🟧 Slogan/stock phrase · ⚖️ Antithesis (home vs exile) |

| 14 | They cannot | Another hinge-line: blocks sharing; in reverse it becomes the start of permission/solidarity. | 🚫 Prohibition framing · 🟦 Enjambment · 🔁 Reversal hinge |

| 15 | Share our food | Presents generosity as threat; implies scarcity and invasion. | 🍞 Concrete detail/symbol · 👥 “our” possessive · 🟥 Irony (reversed) |

| 16 | Share our homes | Intensifies intimacy of “sharing” to provoke discomfort/fear. | 🏠 Symbolic space · 👥 Ingroup boundary · 🟦 Parallel build-up |

| 17 | Share our countries | Moves from private to national—turns compassion into a “border crisis.” | 🗺️ Political register shift · 👥 Nationalism · 🟦 Parallelism |

| 18 | Instead let us | Smooth pivot to “solution”; invites collective action (“us”)—even if harmful. | 👥 Collective voice · 📢 Persuasive pivot · 🟦 Enjambment |

| 19 | Build a wall to keep them out | “Wall” is literal and symbolic: separation, fear, refusal of moral duty. | 🧱 Metaphor/symbol (“wall”) · 🟥 Political allusion · ⚖️ Antithesis (in/out) |

| 20 | It is not okay to say | Polices speech: frames empathy as naïve or unacceptable. | 🚨 Censorship/voice control · 📢 Declarative authority · 🟥 Irony (reversed) |

| 21 | These are people just like us | Core humanizing statement—condemned in forward reading, celebrated in reverse. | 🤝 Humanization · 👥 Inclusive “us” · ⚖️ Antithesis (us/them) |

| 22 | A place should only belong to those who are born there | Blood-and-soil logic: defines belonging by birth, not rights or humanity. | 🟧 Ideological claim · 🧠 Absolutism (“only”) · ⚖️ Exclusion principle |

| 23 | Do not be so stupid to think that | Ad hominem attack: shames the reader into compliance. | 😠 Insult/ad hominem · 📢 Imperative · 🎭 Direct address |

| 24 | The world can be looked at another way | Final line (but first in reverse): announces perspective-shift—invites moral re-reading. | 🔁 Reverse-poem key · ✨ Epiphany/volta · ⚖️ Antithesis (one way/another way) |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

| # | Device | Example from the poem | What it does / explanation |

| 1 | 🔁 Reverse poem / structural reversal | “(now read from bottom to top)” | The poem’s entire meaning flips when read upward: xenophobic rhetoric becomes a compassionate defense of refugees. |

| 2 | 🟥 Irony (structural) | “They have no need of our help” (vs. reversed reading) | The opening claim is undercut by the reverse reading, exposing the speaker’s stance as morally wrong. |

| 3 | 🎭 Dramatic monologue / persona | “So do not tell me” | The poem uses a constructed speaker voicing prejudice; the poet critiques this voice through form. |

| 4 | 🎯 Direct address (apostrophe) | “do not tell me” | Addresses an implied listener/reader, creating confrontation and rhetorical pressure. |

| 5 | 📢 Imperative (command) | “Do not be so stupid to think that” | Commands/shames the audience—shows how hate-speech polices dissent and empathy. |

| 6 | 👥 Inclusive/exclusive pronouns (us vs them) | “you or me”; “We need…”; “Share our…” | Builds an ingroup (“we/our”) against an outgroup (“they/them”). |

| 7 | 🟧 Loaded diction / pejoratives | “Chancers and scroungers” | Uses emotionally charged insults to stigmatize refugees rather than argue logically. |

| 8 | 🧱 Othering | “keep them out” | Frames refugees as outsiders who don’t belong—central to the poem’s critique. |

| 9 | 🟨 Listing / cataloguing | “Chancers and scroungers / Layabouts and loungers…” | A rapid list mimics tabloid rhetoric—creates a pile-on effect of accusations. |

| 10 | 🟪 Imagery | “These haggard faces” | Visual detail makes suffering concrete; in reverse reading it becomes a direct call to empathy. |

| 11 | 💣 Violent imagery | “With bombs up their sleeves” | Injects fear by associating refugees with terrorism—shows how stereotypes are manufactured. |

| 12 | 🟥 Hyperbole / exaggeration | “bombs up their sleeves” | An extreme claim meant to alarm; highlights the irrationality of blanket suspicion. |

| 13 | 🟣 Alliteration | “Layabouts and loungers” | Repeated initial sounds make the insult catchy—revealing how prejudice can be made “memorable.” |

| 14 | 🎴 Metaphor / idiom | “life have dealt a different hand” | Life is framed as a card game; suggests displacement can be a matter of chance. |

| 15 | ⚖️ Antithesis (welcome vs reject) | “They are not / Welcome here” | Places opposing ideas in tension; reversed, it becomes a direct welcome. |

| 16 | 🚪 Motif of borders/containment | “Build a wall… keep them out” | Repeated “in/out” logic stresses exclusion; the wall becomes a symbol of moral division. |

| 17 | 🏠 Symbolism (food/home/country) | “Share our food / Share our homes / Share our countries” | These concrete nouns symbolize resources, safety, and belonging, reframed as threatened possessions. |

| 18 | ⛓️ Parallelism (repetition of structure) | “Share our… / Share our… / Share our…” | Repeating the same grammatical pattern intensifies the argument and builds rhythmic force. |

| 19 | 🟦 Enjambment (line breaks) | “They are not / Welcome here” | The break creates suspense and emphasis; also allows the upward reading to reframe meaning cleanly. |

| 20 | 🔄 Volta / perspective shift | “The world can be looked at another way” | A hinge line: signals the poem’s ethical turn—especially powerful as the first line in reverse. |

Themes: “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

- 🔁 Structural Reversal & Moral Reorientation

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston is ultimately a theme-poem about how meaning, and therefore morality, can be generated by structure, because the instruction to reread from bottom to top converts the same lines into a second, ethically opposed argument. When read downward, the voice sounds clipped and authoritative, so that exclusion feels like practicality; when read upward, however, the poem performs a correction in which welcome replaces rejection and empathy replaces suspicion, thereby exposing that the first “common-sense” stance was produced by sequencing rather than truth. This reversible design turns the reader into an active participant, since one must perform the poem’s transformation to understand it, and it dramatizes how easily language can be arranged to make cruelty appear reasonable. In this sense, the poem’s form becomes its moral lesson: it trains readers to distrust the first, easiest reading, to reconsider their interpretive habits, and to choose a perspective that can hold human dignity in view. - 🧨 Xenophobia, Stereotypes, and the Manufacture of Threat

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston foregrounds how xenophobia is built from rhetorical shortcuts, because the speaker replaces people with pejoratives—“chancers,” “scroungers,” “cut-throats,” “thieves”—and then treats those names as if they were evidence. The accumulation works like a verbal drumbeat, so that repetition supplies certainty where facts are missing, while the sudden escalation to terror imagery (“bombs up their sleeves”) manufactures fear through a vivid allegation that is designed to stick. As these claims intensify, the poem reveals the moral mechanics of stereotyping: once a group is framed as inherently parasitic or violent, compassion can be rebranded as foolishness, and harsh policies can be presented as self-defense. Yet the reverse reading functions as an exposure device, because it shows that the threatening portrait is a crafted performance rather than a stable reality, and it implies that such rhetoric survives less by accuracy than by its ability to sound decisive, to shame disagreement, and to discourage the imaginative identification that would puncture the myth. - 🧱 Belonging, Borders, and the Politics of Possession

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston treats belonging as an argument about possession, because the repeated emphasis on “our food,” “our homes,” and “our countries” turns community into property and turns sharing into a kind of loss. This possessive grammar creates an exclusionary logic in which birth becomes the primary credential for moral entitlement, so that the claim that a place “should only belong to those who are born there” operates as a gate that converts geography into destiny. The “wall” then becomes both policy and symbol, since it represents a desire to solve complex displacement with a simple barrier, and it externalizes an inner refusal to imagine mutual obligation across lines of nationality. By staging these phrases as a persuasive script, the poem suggests that borders are guarded not only by fences but by stories, because the narrative of scarcity and invasion makes refusal feel responsible, while the reverse reading reveals that another narrative—based on inclusion—can be assembled from the same language if we relinquish the impulse to treat belonging as private ownership. - 🤝 Shared Humanity, Contingency, and the Discipline of Empathy

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston frames empathy as an intellectual and ethical discipline rather than a soft emotion, because it insists that the distance between “us” and “them” is often a matter of contingency: “These haggard faces could belong to you or me,” if “life [had] dealt a different hand.” By grounding identification in chance, the poem dismantles the comforting idea that suffering happens only to others for reasons that must somehow be deserved, and it exposes how privilege can quietly masquerade as merit. At the same time, the poem demonstrates that sympathy can be socially policed, since the downward reading mocks alternative viewpoints as stupid, whereas the upward reading restores that alternative as lucid and humane. The final invitation—that “The world can be looked at another way”—becomes the thematic hinge, because it asks readers to practice a different kind of seeing in which refugees are not reduced to threats or burdens but recognized as people whose vulnerability mirrors our own, and whose welcome measures the moral maturity of the societies they approach.

Literary Theories and “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

| Theory ) | What it focuses on | References from the poem (with line nos.) | What it reveals in “Refugees” |

| 🔵 Reader-Response | Meaning is produced in the act of reading; rereading changes interpretation. | “(now read from bottom to top)” (l.25); “The world can be looked at another way” (l.24). | The poem forces the reader to “perform” empathy: the same text generates hostility top→bottom, then reverses into compassion bottom→top—showing how interpretation (and prejudice) can be structurally “learned” and unlearned. |

| 🟣 Deconstruction (Derridean) | Unstable meaning; binary oppositions (us/them) collapse under reversal/contradiction. | “They are not / Welcome here” (ll.10–11) vs “These are people just like us” (l.21); “Build a wall” (l.19) vs “Share our…homes…countries” (ll.15–17). | Bilston undoes the “us vs. them” binary: the poem’s structure demonstrates that the certainty behind exclusion (“Welcome here,” “Build a wall”) is textually reversible, exposing how fragile and constructed such “truths” are. |

| 🟢 Postcolonial Theory | Othering, borders, belonging, migration, and who gets to claim “home.” | “Go back to where they came from” (l.13); “A place should only belong to those who are born there” (l.22); “These haggard faces could belong to you or me” (l.3). | The poem stages the politics of belonging: nationalist purity claims (l.22) and expulsion rhetoric (l.13) are countered by shared human contingency (l.3), critiquing how migrants/refugees are “othered” and denied co-belonging. |

| 🔴 Marxist / Materialist Criticism | Scarcity narratives, resource anxiety, classed blame, and “deserving/undeserving” labels. | “Chancers and scroungers” (l.6); “They cannot / Share our food…homes…countries” (ll.14–17). | Xenophobia is shown as a scarcity story: refugees are framed as parasites (l.6) who threaten “our” resources (ll.14–17). The reversal exposes this as ideological—an attempt to protect perceived economic comfort by policing who counts as worthy. |

Critical Questions about “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

- 🔵 Critical Question 1: How does the poem’s reversible form change the reader’s ethical position toward refugees?

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston begins by drawing the reader into a fluent monologue of suspicion—“Chancers and scroungers,” “Cut-throats and thieves”—that hardens into exclusion (“They are not / Welcome here”) and culminates in the command to expel (“Go back to where they came from”), so that prejudice initially presents itself as ordinary “common sense.” Yet the instruction “(now read from bottom to top)” operates as a formal trigger for moral reorientation, because the same lines, reordered, turn into their own rebuttal, ending in the unsettling recognition that “These haggard faces could belong to you or me” and that “The world can be looked at another way.” Because this change depends on the reader’s active participation, the poem makes ethics experiential: you do not merely witness a shift in viewpoint; you perform it. In that performance, hostility is revealed as a product of framing and sequence, while empathy emerges as disciplined rereading, suggesting that moral perception is not fixed but continuously made and remade through language. - 🟣 Critical Question 2: What kind of speaking voice is performed, and how does satire avoid becoming endorsement?

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston ventriloquizes a recognizable public voice—defensive, impatient, and rhetorically certain—announced by the hectoring “So do not tell me,” which pre-empts dialogue by treating compassion as stupidity. This voice depends on ready-made stereotypes (“Layabouts and loungers”) and escalates them into securitized fantasy (“With bombs up their sleeves”), so fear can pass as realism; however, the poem refuses to let this performance settle into mere repetition. When reversed, the diction collapses into self-contradiction, revealing that the speaker’s certainty is a recycled script rather than an argument, driven by momentum more than evidence. Satire here works structurally: it allows the hostile rhetoric to display its persuasive rhythm, then forces a second reading in which that rhythm becomes an object of critique. The result is ethically uncomfortable but precise, because the reader is briefly enlisted by the fluency of the voice and then confronted with how easily such fluency manufactures consensus—until the frame is altered and the “obviousness” evaporates. - 🟢 Critical Question 3: How does the poem construct “us” and “them,” and what happens when that boundary collapses?

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston constructs the “us/them” divide through pronouns, ownership, and imperatives: “They” becomes an abstract mass, while “our food,” “our homes,” and “our countries” convert shared life into guarded property, and “We should make them” turns exclusion into collective duty. The boundary is then moralized by a chain of accusations—parasites (“scroungers”), idlers (“layabouts”), criminals (“thieves”)—which makes refusal of welcome seem prudent rather than cruel, climaxing in the spatial fantasy of control, “Build a wall to keep them out.” Yet the reverse reading dismantles this architecture, because the same lines rebuild an opposing ethic: “These are people just like us,” previously framed as unacceptable, becomes central, and “These haggard faces could belong to you or me” replaces entitlement with contingency—“Should life have dealt a different hand.” The poem therefore suggests that borders are first built in language, and that when language is rearranged, belonging can be reimagined without changing a single word, exposing exclusion as rhetorical construction before it becomes political practice. - 🔴 Critical Question 4: Why has the poem remained widely shared, and what does its popularity suggest about contemporary discourse on migration?

“Refugees” by Brian Bilston has remained widely shared because it is compact, teachable, and dramatically self-reversing: its short lines resemble slogans, yet its built-in instruction to reread transforms a xenophobic script into its own undoing, producing a moral turn that readers can feel immediately. The poem resonates because the hostile phrases—“Go back to where they came from,” the claim that refugees “cannot / Share our” resources, and the assertion that “A place should only belong to those who are born there”—sound painfully familiar in public speech, so the text functions like a mirror of everyday discourse rather than an abstract lecture. By compelling reversal, Bilston offers a practical intervention: a method for interrupting dehumanization by exposing how quickly language can make cruelty seem reasonable, and how quickly the same language can be reclaimed for solidarity. At the same time, the poem’s virality reflects a contemporary hunger for moral clarity that fits compressed attention economies, even if the structural causes of displacement remain largely offstage.

Literary Works Similar to “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

- 🧭 “Home” (Warsan Shire) — Like “Refugees,” it confronts anti-refugee sentiment by insisting that flight happens under coercion and terror, making empathy an ethical necessity rather than a sentimental choice.

- 🕯️ “Refugee Blues” (W. H. Auden) — Like “Refugees,” it exposes how societies normalize exclusion, using a tightly patterned voice to show refugees being refused safety, dignity, and belonging.

- 🗽 “The New Colossus” (Emma Lazarus) — Like “Refugees,” it counters nativist gatekeeping with an explicit moral vision of welcome, redefining the nation’s identity through hospitality to the displaced.

- 🧱 “The Hangman” (Maurice Ogden) — Like “Refugees,” it dramatizes how public language and passive complicity enable cruelty, showing how exclusionary rhetoric escalates into collective harm.

Representative Quotations of “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

| Quotation | Context in the poem | Theoretical perspective |

| 🔁 “The world can be looked at another way” | This closing line is the poem’s hinge; when the text is read bottom-to-top, it becomes the opening invitation to reinterpret refugees and the rhetoric around them. | Reader-Response Theory: the poem makes meaning depend on the reader’s active rereading, showing that interpretation is an ethical act rather than a passive reception. |

| 🎭📢 “Do not be so stupid to think that” | The speaker ridicules empathy and polices acceptable opinion; the insult functions as social pressure to conform to hostility. | Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA): this line demonstrates how power works through language by shaming dissent, discrediting counter-views, and manufacturing “common sense.” |

| 🧱🗺️ “A place should only belong to those who are born there” | A nativist principle is presented as a rule of belonging, turning birthplace into moral entitlement and outsiders into permanent intruders. | Nationalism / Nativism (Political Theory): it frames citizenship as inheritance, not rights, legitimizing exclusion through “natural” claims about land and identity. |

| 🤝👥 “These are people just like us” | A direct humanizing statement that is condemned in the forward reading, but becomes morally central and affirmed in the reverse reading. | Ethics of Care / Humanitarian Ethics: it foregrounds relational responsibility and shared vulnerability, arguing that moral recognition begins with likeness rather than difference. |

| 🧱🚧 “Build a wall to keep them out” | The poem condenses a whole policy posture into one image: separation as solution, fear as justification, and refusal as protection. | Border Theory / Spatial Politics: the “wall” symbolizes how states and communities convert anxiety into architecture—material boundaries that mirror ideological ones. |

| 👥🔒 “Share our food / Share our homes / Share our countries” | The repeated “our” constructs ownership, while “share” is framed as threat; the escalation from food→homes→countries widens the panic from private to national. | Social Identity Theory: pronouns (“our”) intensify ingroup cohesion and outgroup suspicion, making solidarity feel like loss and exclusion feel like self-defense. |

| 🚨🗣️ “It is not okay to say” | The speaker tries to ban certain moral language, treating empathy as taboo and restricting what can be voiced publicly. | Hegemony (Gramscian lens): it shows how dominant attitudes sustain themselves by controlling the boundaries of “sayable” discourse and delegitimizing humane frames. |

| 🧨🧱 “Go back to where they came from” | A stock xenophobic slogan that erases the reasons people flee and converts displacement into a punishable intrusion. | Postcolonial / Migration Studies lens: it exposes how “outsider” narratives simplify histories of conflict and mobility, using origin as a weapon to deny refuge and rights. |

| 💣🟥 “With bombs up their sleeves” | A fear-triggering accusation that jumps from refugeehood to terrorism, aiming to make suspicion feel prudent and urgent. | Securitization Theory (IR): it shifts refugees into the category of “security threat,” enabling exceptional, harsh responses by treating compassion as risk. |

| 🎴🟪 “These haggard faces could belong to you or me / Should life have dealt a different hand” | The poem briefly insists on contingency and identification: suffering is not a foreign trait but a possible human fate shaped by chance. | Moral Philosophy (Contingency & Cosmopolitanism): the “dealt a hand” metaphor universalizes vulnerability, supporting a cosmopolitan claim that obligations extend beyond borders. |

Suggested Readings: “Refugees” by Brian Bilston

Books

- Bilston, Brian. Refugees. Illustrated by José Sanabria, Palazzo Editions, 2019. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=pVjOvwEACAAJ. Accessed 1 Dec. 2025.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. Strangers at Our Door. Polity Press, 2016. Polity, https://www.politybooks.com/bookdetail/?isbn=9781509512164. Accessed 1 Dec. 2025.

Academic articles

- Weima, Yolanda. “‘Is it Commerce?’: Dehumanization in the Framing of Refugees as Resources.” Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, vol. 37, no. 2, 2021, pp. 20–28. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.40796. Accessed 1 Dec. 2025.

- Loupaki, Elpida. “EU Legal Language and Translation—Dehumanizing the Refugee Crisis.” International Journal of Language & Law, vol. 7, 2018, pp. 97–116. https://www.languageandlaw.eu/jll/article/download/53/36/177. Accessed 1 Dec. 2025.

Poem websites

- Bilston, Brian. “Refugees.” Brian Bilston, 23 Mar. 2016, https://brianbilston.com/2016/03/23/refugees/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2025.

- Bilston, Brian. “Refugees.” University of Portland (PDF), https://www.up.edu/garaventa/files/fildg%20files/refugees.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec. 2025.