Introduction: “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

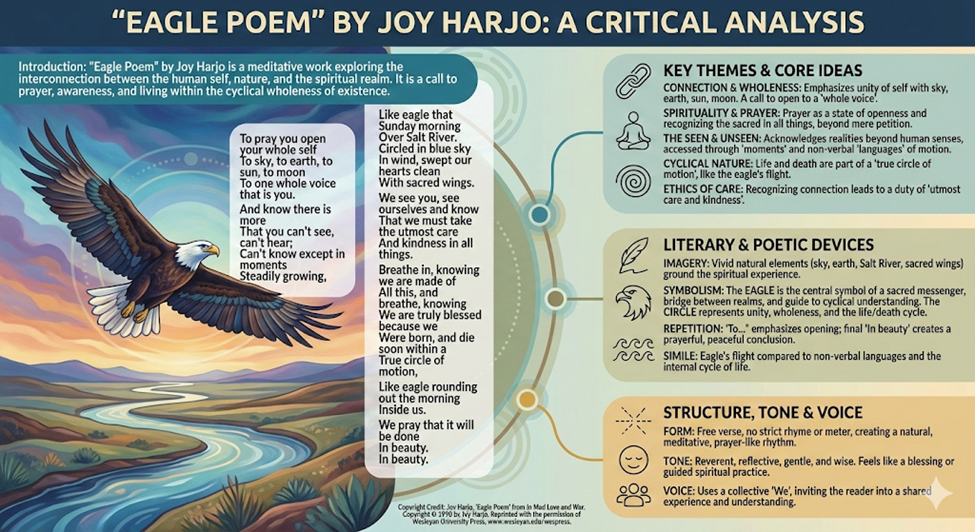

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo first appeared in 1990 in her poetry collection In Mad Love and War, and it articulates a spiritually grounded vision of interconnected existence rooted in Indigenous epistemology and cosmology. The poem’s central idea is prayer as an act of total openness and relational awareness, signaled at the outset—“To pray you open your whole self / To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon”—where the self is dissolved into a living continuum that includes the natural and the sacred. Harjo advances a non-verbal, experiential understanding of knowledge through “languages / That aren’t always sound but other / Circles of motion,” emphasizing cyclical time and holistic perception rather than linear rationality. The eagle functions as a sacred mediator between human and cosmic realms—“Like eagle that Sunday morning / Over Salt River”—whose circling flight “swept our hearts clean / With sacred wings,” enacting spiritual renewal and ethical responsibility. The poem’s enduring popularity derives from its lyrical simplicity, ceremonial cadence, and universal ethical appeal, culminating in the injunction to live with “the utmost care / And kindness in all things,” and its resonant closure—“In beauty. / In beauty.”—which echoes Indigenous prayer traditions while offering a contemplative, inclusive spirituality that speaks across cultures and generations.

Text: “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

To pray you open your whole self

To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon

To one whole voice that is you.

And know there is more

That you can’t see, can’t hear;

Can’t know except in moments

Steadily growing, and in languages

That aren’t always sound but other

Circles of motion.

Like eagle that Sunday morning

Over Salt River. Circled in blue sky

In wind, swept our hearts clean

With sacred wings.

We see you, see ourselves and know

That we must take the utmost care

And kindness in all things.

Breathe in, knowing we are made of

All this, and breathe, knowing

We are truly blessed because we

Were born, and die soon within a

True circle of motion,

Like eagle rounding out the morning

Inside us.

We pray that it will be done

In beauty.

In beauty.

Copyright Credit: Joy Harjo, “Eagle Poem” from In Mad Love and War. Copyright © 1990 by Joy Harjo. Reprinted with the permission of Wesleyan University Press,

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress.

Annotations: “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

| Stanza / Line(s) | Annotation (Meaning & Function) | Literary Devices |

| “To pray you open your whole self / To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon” | The poem opens by redefining prayer as total openness rather than verbal petition. The speaker urges surrender of the self to cosmic forces, presenting spirituality as relational and ecological. Prayer is framed as receptivity to the universe rather than appeal to a distant deity. | Anaphora 🔁, Cosmic Imagery 🌍, Invocation 🕯️, Parallelism 🔄 |

| “To one whole voice that is you.” | Prayer is internalized; the sacred voice is not external authority but the unified self in harmony with existence. Identity and spirituality merge, rejecting dualism between human and divine. | Metaphor 🪶, Introspection 🧠, Unity of Self & Nature 🌀 |

| “And know there is more / That you can’t see, can’t hear; / Can’t know except in moments” | Human perception is acknowledged as limited. True understanding arrives only fleetingly, emphasizing humility and reverence before mystery. Knowledge is experiential rather than rational or permanent. | Epistemic Humility 🔍, Parallelism 🔄, Minimalism 🌱 |

| “Steadily growing, and in languages / That aren’t always sound but other / Circles of motion.” | Meaning expands beyond spoken language into movement, rhythm, and pattern. Spiritual communication occurs through motion and silence, aligning knowledge with lived experience. | Motion Imagery 🌊, Circular Imagery 🔵, Metaphor 🪶 |

| “Like eagle that Sunday morning / Over Salt River.” | The simile introduces the eagle as a concrete spiritual emblem grounded in lived reality and specific geography, blending the sacred with the everyday. | Simile 🔗, Symbolism 🔍, Sacred Place 🌄 |

| “Circled in blue sky / In wind, swept our hearts clean / With sacred wings.” | The eagle’s flight becomes an act of spiritual purification. Nature is portrayed as an active moral force capable of cleansing human consciousness. | Personification 🕊️, Imagery 🌬️, Extended Metaphor 🦅, Alliteration 🔔 |

| “We see you, see ourselves and know” | Observation of the eagle leads to self-recognition. Knowledge arises through reflection, reinforcing Indigenous epistemology where learning is relational. | Introspection 🧠, Parallelism 🔄, Unity of Self & Nature 🌀 |

| “That we must take the utmost care / And kindness in all things.” | Ethical responsibility emerges organically from spiritual awareness. Morality is ecological and inclusive, extending care to all existence. | Didactic Tone 📜, Ethical Imperative ⚖️, Universalism 🌈 |

| “Breathe in, knowing we are made of / All this, and breathe, knowing” | Breath functions as a sacred connector between body, spirit, and cosmos. Humans are composed of the same elements they revere. | Breath Imagery 🌬️, Repetition 🔁, Native Cosmology 🌈 |

| “We are truly blessed because we / Were born, and die soon within a / True circle of motion,” | Mortality is framed as blessing, not tragedy. Life and death are equal movements within an eternal cycle, encouraging acceptance and humility. | Temporal Awareness ⏳, Circular Imagery 🔵, Philosophical Paradox ♾️ |

| “Like eagle rounding out the morning / Inside us.” | The eagle is internalized, signifying spiritual integration. Nature’s rhythm becomes part of human consciousness. | Extended Metaphor 🦅, Internalization 🧠, Symbolism 🔍 |

| “We pray that it will be done / In beauty. / In beauty.” | The poem ends with a ceremonial refrain. “Beauty” signifies harmony, balance, and ethical living rather than mere aesthetics, closing the prayer ritually. | Refrain 🌸, Minimalism 🌱, Prayer Form 🛐, Ritual Closure 🔔 |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

| Literary Device | Definition | Example from the Poem | Explanation |

| Alliteration 🔔 | Repetition of initial consonant sounds | “swept our hearts clean / sacred wings” | The soft s sound creates a hushed, cleansing, meditative effect. |

| Anaphora 🔁 | Repetition at the beginning of successive lines | “To pray you open… / To sky, to earth…” | Establishes ritual rhythm and ceremonial invocation. |

| Assonance 🎵 | Repetition of vowel sounds | “blue sky / true circle” | Produces musical calm and reinforces harmony. |

| Circular Imagery 🔵 | Recurrent images of cycles or circles | “circle of motion” | Reflects Indigenous belief in cyclical time and existence. |

| Cosmic Imagery 🌍 | Celestial or universal imagery | “sky… earth… sun… moon” | Places prayer within a vast, sacred cosmos. |

| Extended Metaphor 🕊️ | Sustained metaphor across lines | The eagle throughout the poem | The eagle embodies spiritual vision, balance, and transcendence. |

| Imagery 🌬️ | Sensory descriptive language | “wind, swept our hearts clean” | Makes spirituality tangible and experiential. |

| Introspection 🧠 | Reflection on inner self | “see ourselves and know” | Prayer becomes self-recognition and awareness. |

| Invocation 🕯️ | Calling upon a sacred presence | “To pray you open your whole self” | Frames the poem as a ceremonial address. |

| Metaphor 🪶 | Implied comparison | “swept our hearts clean” | Spiritual purification likened to a physical cleansing. |

| Minimalism 🌱 | Economy of language | “In beauty.” | Brevity heightens reverence and solemnity. |

| Motion Imagery 🌊 | Emphasis on movement | “circles of motion” | Suggests spiritual life as dynamic and ongoing. |

| Native Cosmology 🌈 | Indigenous worldview in imagery | “we are made of / all this” | Affirms interconnectedness of humans and nature. |

| Parallelism 🔄 | Similar grammatical structure | “can’t see, can’t hear; / can’t know” | Reinforces human limitation and humility. |

| Personification 🕊️ | Human traits given to non-human | “wind… swept our hearts clean” | Nature acts as a conscious, sacred agent. |

| Prayer Form 🛐 | Poem structured as prayer | Entire poem | Blends poetry with spiritual ritual. |

| Refrain 🌸 | Repeated concluding phrase | “In beauty.” | Provides ceremonial closure and affirmation. |

| Symbolism 🔍 | Concrete object representing abstract ideas | Eagle | Symbolizes sacred vision and moral responsibility. |

| Temporal Awareness ⏳ | Awareness of time and mortality | “born, and die soon” | Highlights life’s brevity within an eternal cycle. |

| Unity of Self & Nature 🌀 | Fusion of inner and outer worlds | “Inside us” | Spiritual realization occurs through oneness with nature. |

Themes: “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

- ◆ Sacred Interconnectedness of All Being

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo foregrounds a holistic worldview in which prayer is not a ritualized utterance but a complete opening of the self to existence itself, binding sky, earth, sun, and moon into a single continuum of being. The poem presents spirituality as an experiential awareness that exceeds sensory perception, emphasizing that deeper knowledge emerges only in fleeting, intuitive moments rather than through fixed doctrines. The eagle’s circling flight functions as a living symbol of unity, visually affirming an Indigenous cosmology in which humans are inseparable from the natural world. By aligning the human voice with cosmic forces, the poem dissolves divisions between self and environment, spirit and matter. Prayer thus becomes an act of recognition, asserting that human life is composed of the same elements it venerates, and that sacredness lies in relational existence rather than transcendental distance.

- ✦ Prayer as Embodied and Communal Practice

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo reconceptualizes prayer as an embodied and communal discipline rather than a private or purely verbal act. The call to “open your whole self” situates prayer in breath, perception, and bodily presence, suggesting that spirituality is lived through attentive participation in the world. Harjo’s repeated use of the collective “we” underscores that prayer is sustained through shared awareness and mutual responsibility. When the eagle “swept our hearts clean,” the cleansing described is emotional and communal, emphasizing restoration through collective experience. Prayer, therefore, becomes a way of inhabiting the world ethically, where awareness translates into care. The poem asserts that spirituality is not removed from daily life but enacted through how individuals breathe, observe, and remain accountable to one another.

- ✶ Cyclicality of Life, Death, and Renewal

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo articulates a cyclical vision of existence in which life and death are integrated within an ongoing rhythm rather than understood as absolute beginnings or endings. The recurring imagery of circles, especially in the eagle’s flight, symbolizes continuity and return, central to Indigenous understandings of time and being. Acknowledging that humans “die soon” does not diminish life’s value; instead, it intensifies reverence for existence by situating mortality within a larger, sustaining cycle. The eagle’s motion becomes internalized, suggesting that renewal occurs when individuals recognize their place within this eternal movement. By rejecting linear conceptions of time, the poem offers a philosophy in which meaning arises through participation in enduring natural patterns rather than through permanence or accumulation.

- ☼ Ethics of Care, Kindness, and Beauty

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo culminates in a moral vision that links spiritual awareness directly to ethical responsibility. Recognizing interconnectedness obliges humans to act with “utmost care and kindness,” transforming insight into conduct. The repeated invocation of “in beauty” frames ethical living as both a spiritual and aesthetic imperative, where harmony and compassion become measures of moral integrity. Beauty in the poem is not decorative but relational, emerging from balanced relationships with others and the natural world. Harjo thus aligns spirituality with an ethics of attentiveness, humility, and gratitude, insisting that reverence must manifest in everyday actions. The poem ultimately proposes that to live prayerfully is to live beautifully, sustaining life through mindful and compassionate engagement.

Literary Theories and “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

| Theory | Core Concept | Application to the Poem | Key Text Reference |

| 🌿 Ecocriticism (Literature & Environment) | Examines the relationship between humans and the natural world, often rejecting the idea that nature is just a “setting” for human drama. | Harjo dissolves the barrier between the human “self” and the environment. The poem argues that humans are biologically and spiritually continuous with the ecosystem. The eagle is not just a symbol, but an active participant that “sweeps” the human heart, suggesting nature has agency and power over people, not the reverse. | “To pray you open / your whole self / To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon” “We are made of / All this” |

| ✊ Postcolonialism (Indigenous Studies) | Focuses on literature by colonized peoples that reclaims cultural identity, resists dominant Western narratives, and validates indigenous knowledge. | The poem reclaims the concept of “prayer” from Western religious structures, reframing it through Indigenous epistemology (ways of knowing). The specific reference to “Salt River” and the concluding chant “In beauty” re-centers the geography and philosophy of the Pima, Maricopa, and Navajo peoples, asserting their survival and spiritual validity. | “In beauty. / In beauty.” (Allusion to the Navajo Night Chant) “Over Salt River.” (Reclaiming sacred geography) |

| 🧠 Psychoanalytic (Jungian Archetypes) | Analyzes texts through psychological symbols, particularly the “collective unconscious”—universal symbols shared across humanity. | The Eagle serves as a “Mana Personality” or archetype of the Higher Self/Spirit. The Circle functions as a “Mandala,” a symbol of the psyche seeking wholeness. The poem describes the Ego (the conscious self) realizing it is part of a larger, unconscious “circle of motion,” leading to psychological integration. | “Like eagle rounding out the morning / Inside us.” (Internalization of the archetype) “Know there is more / That you can’t see” (The Unconscious) |

| 🏗️ Structuralism (Patterns & Binaries) | Looks at the underlying structures (grammar, signs, binaries) that construct meaning, rather than just the content. | The poem is structured to collapse binary oppositions: Sound vs. Silence, Life vs. Death, Self vs. Nature. Harjo removes conjunctions (asyndeton) and punctuation to structurally mimic the “circle.” The text is a closed system where the beginning (prayer) and end (beauty) are structurally identical, reinforcing the theme of cyclical time. | “Born, and die soon” (Collapsing the binary of life/death) “Languages / That aren’t always sound” (Deconstructing the sign of language) |

Critical Questions about “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

🦅 Critical Question 1: How does the eagle function as a spiritual and ethical symbol in the poem?

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo presents the eagle as far more than a natural creature; it functions as a sacred mediator between the human and cosmic realms, embodying spiritual vision, ethical responsibility, and transcendence. The eagle’s circular flight symbolizes a worldview rooted in balance and continuity rather than dominance or linear progress. By observing the eagle “swept our hearts clean / With sacred wings,” the speaker suggests moral purification achieved not through doctrine but through attentive communion with nature. The eagle becomes an ethical mirror, compelling humans to recognize their obligation toward “the utmost care / And kindness in all things.” Importantly, the bird does not instruct verbally; instead, its silent motion models an alternative epistemology grounded in observation, humility, and reverence. Thus, the eagle functions simultaneously as symbol, guide, and conscience, reinforcing Indigenous values where ethical living emerges organically from harmony with the natural world rather than from imposed authority.

🌍 Critical Question 2: In what ways does the poem redefine prayer beyond conventional religious practice?

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo radically redefines prayer as an embodied, ecological, and inclusive act rather than a formalized religious ritual confined to words or institutions. Prayer, in the poem, begins with opening “your whole self” to the elements—sky, earth, sun, and moon—thereby dissolving the boundary between the sacred and the material. Harjo’s conception of prayer privileges attentiveness, breath, and presence over verbal articulation, emphasizing that some truths exist in “languages / That aren’t always sound.” This redefinition challenges Western theological frameworks that prioritize speech, creed, or hierarchy, replacing them with an Indigenous spiritual epistemology grounded in relational awareness. Prayer becomes a mode of ethical living and perceptual clarity, a continuous state of being rather than a discrete act. Through this expanded vision, Harjo positions prayer as a daily, reciprocal engagement with the living world, accessible to all who are willing to listen and observe with humility.

🌀 Critical Question 3: How does the motif of circular motion shape the poem’s philosophy of life and death?

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo employs circular motion as a central philosophical motif to articulate a worldview in which life and death are interconnected phases within an ongoing cosmic rhythm. The repeated references to “circles of motion” and the “true circle of motion” reject linear conceptions of time that frame birth and death as absolute beginnings and endings. Instead, Harjo presents existence as cyclical, regenerative, and continuous, aligning human mortality with natural processes such as flight, wind, and breath. The acknowledgment that humans are “born, and die soon” is not framed as tragic but as an integral component of a sacred order. This perspective fosters acceptance rather than fear, humility rather than conquest. By internalizing the circle—“inside us”—the poem suggests that spiritual maturity involves recognizing oneself as part of a larger, enduring pattern, where meaning arises not from permanence but from participation in the ongoing motion of the universe.

🌸 Critical Question 4: What is the significance of the poem’s ending refrain “In beauty”?

“Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo concludes with the repeated refrain “In beauty,” a phrase that functions as both a ceremonial closure and a profound ethical aspiration. Rather than serving as mere aesthetic appreciation, “beauty” here signifies balance, harmony, and right relationship with the world, echoing Indigenous philosophical traditions where beauty is inseparable from moral conduct. The repetition transforms the phrase into a blessing or prayer, reinforcing the poem’s ritualistic structure and inviting the reader to internalize its values. Ending the poem in this manner shifts emphasis from explanation to affirmation, suggesting that spiritual understanding culminates not in argument but in lived practice. The refrain also universalizes the poem’s message, offering beauty as a guiding principle for action, perception, and responsibility. By closing on these words, Harjo leaves the reader within a sacred cadence, reminding us that to live “in beauty” is both a spiritual goal and an ethical commitment.

Literary Works Similar to “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

- 🦅 “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

This poem parallels “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo in its meditative spirituality and its turn toward the natural world as a source of inner restoration, presenting nature as a living presence that heals anxiety and reconnects the self to a larger, sustaining order. - 🌕 “Prayer for the Earth” by Gary Snyder

Like “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo, this poem articulates an ecological spirituality grounded in Indigenous and Eastern philosophies, emphasizing reverence for the earth, ritualized awareness, and ethical responsibility toward all forms of life. - 🌿 “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” by Walt Whitman

This poem resembles “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo in its rejection of abstract, analytical knowledge in favor of direct, experiential communion with the natural world, privileging silent wonder and intuitive understanding over intellectual explanation.

Representative Quotations of “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

| Quotation | Context & Theoretical Perspective | Explanation |

| 🕯️ “To pray you open your whole self” | Context: Opening invocation · Theory: Indigenous Spirituality / Phenomenology | Prayer is defined as total openness of being rather than ritualized speech, foregrounding embodied awareness and lived spirituality. |

| 🌍 “To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon” | Context: Cosmic address · Theory: Ecocriticism / Native Cosmology | The sacred is distributed across natural elements, rejecting anthropocentric or hierarchical theology. |

| 🧠 “To one whole voice that is you.” | Context: Interiorization of prayer · Theory: Postcolonial Identity / Indigenous Epistemology | Spiritual authority is internal rather than institutional, affirming selfhood rooted in harmony rather than domination. |

| 🔍 “There is more / That you can’t see, can’t hear” | Context: Limits of perception · Theory: Epistemological Critique | Challenges rationalist knowledge systems by privileging mystery and experiential knowing. |

| 🌀 “Languages / That aren’t always sound but other / Circles of motion.” | Context: Non-verbal knowledge · Theory: Semiotics / Indigenous Knowledge Systems | Meaning exists in movement and rhythm, expanding language beyond speech and text. |

| 🦅 “Like eagle that Sunday morning” | Context: Introduction of central symbol · Theory: Symbolism / Sacred Ecology | The eagle becomes a mediator between human consciousness and the cosmic order. |

| 🌬️ “Swept our hearts clean / With sacred wings.” | Context: Spiritual purification · Theory: Ecocriticism / Ritual Theory | Nature performs ethical cleansing, reversing human claims of mastery over the natural world. |

| ⚖️ “We must take the utmost care / And kindness in all things.” | Context: Ethical conclusion · Theory: Environmental Ethics | Moral responsibility emerges organically from spiritual awareness rather than law or command. |

| ⏳ “We were born, and die soon within a / True circle of motion,” | Context: Reflection on mortality · Theory: Cyclical Time Theory / Indigenous Philosophy | Life and death are framed as complementary movements within an eternal cycle, not opposites. |

| 🌸 “In beauty. / In beauty.” | Context: Ritual closure · Theory: Aesthetic Ethics / Indigenous Philosophy | “Beauty” signifies harmony, balance, and right living, concluding the poem as a blessing rather than an argument. |

Suggested Readings: “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

Books

- Harjo, Joy. She Had Some Horses. Wesleyan University Press, 1983.

- Harjo, Joy. In Mad Love and War. Wesleyan University Press, 1990.

Academic Articles

- Fleih Hassan, Mohamad. “Ecocritical Reading of Joy Harjo’s ‘Eagle Poem’ & ‘Remember’.” Journal of AlMaarif University College, vol. 35, no. 4, 2024, pp. 288–301.

- Hussain, Azfar. “Joy Harjo and Her Poetics as Praxis: A ‘Postcolonial’ Political Economy of the Body, Land, Labor, and Language.” Wíčazo Ša Review, vol. 15, no. 2, 2000, pp. 27–61. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1409462.

Poem Websites

- “Eagle Poem.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46545/eagle-poem.

- “Eagle Poem by Joy Harjo.” PoemAnalysis.com, https://poemanalysis.com/joy-harjo/eagle-poem/.