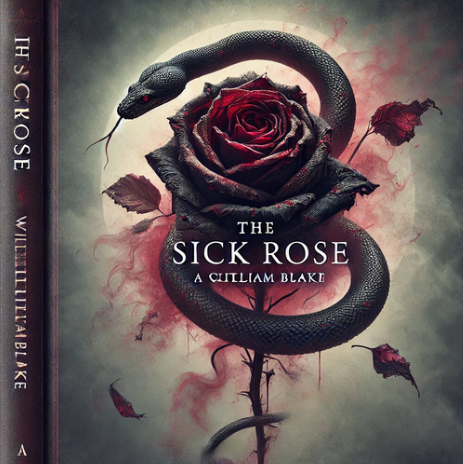

Introduction: “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

“The Sick Rose” by William Blake, first appeared in 1794 as part of his collection Songs of Experience, explores the themes of corruption, fragility, and the destructive forces of secrecy and decay. Through the metaphor of a rose and an invisible worm, Blake explores the interplay between innocence and experience, love and destruction. The poem’s enduring popularity as a textbook piece stems from its rich symbolism, brevity, and layered interpretations, making it an excellent subject for literary analysis. Its ambiguity and universal themes allow readers to engage with questions of morality, human nature, and emotional vulnerability across various contexts.

Text: “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

O Rose thou art sick.

The invisible worm,

That flies in the night

In the howling storm:

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy:

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

Annotations: “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

| Line | Annotation |

| O Rose thou art sick. | The “Rose” symbolizes purity, love, or beauty, while “sick” introduces the theme of corruption or vulnerability. The exclamation reflects urgency and despair. |

| The invisible worm, | The “worm” represents a hidden, destructive force such as deceit, guilt, or a corrupting influence. Its invisibility emphasizes its stealthy and insidious nature. |

| That flies in the night | The worm operates in secrecy (“night”), alluding to clandestine actions, the unconscious mind, or hidden emotions. “Flies” suggests swiftness and elusiveness. |

| In the howling storm: | The “storm” evokes chaos and turmoil, amplifying the destructive environment in which the worm thrives. It could symbolize emotional or societal unrest. |

| Has found out thy bed | The “bed” is a metaphor for intimacy, vulnerability, or the sanctity of life and love. The worm’s intrusion represents a breach of purity or trust. |

| Of crimson joy: | “Crimson joy” juxtaposes passion and vitality (crimson) with corruption and loss, hinting at the duality of love’s pleasures and potential destructiveness. |

| And his dark secret love | The “dark secret love” implies hidden desires or forbidden love that corrupts and destroys. The darkness contrasts with the rose’s vibrant innocence. |

| Does thy life destroy. | The culmination of destruction; the worm’s actions symbolize how hidden evils, secrecy, or corruption can lead to the demise of beauty, love, or innocence. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

| Literary Device | Example | Explanation |

| Ambiguity | “Dark secret love” | The phrase allows multiple interpretations, such as forbidden love, hidden desires, or malevolent intentions. |

| Apostrophe | “O Rose thou art sick.” | The speaker directly addresses the Rose, personifying it and creating a dramatic tone. |

| Connotation | “Crimson joy” | The phrase suggests both the passion of love and the perilous, corrupting aspects of desire. |

| Contrast | “Crimson joy” vs. “Dark secret love” | Juxtaposition of positive (joy) and negative (dark, secret) elements highlights the duality of emotions. |

| Enjambment | Lines 1–2 (O Rose…worm) | The sentence flows beyond the line break, creating a sense of continuity and urgency. |

| Imagery | “Howling storm” | Evokes a vivid sense of chaos, suggesting a turbulent emotional or physical state. |

| Irony | “Crimson joy…life destroy” | The destructive nature of love or passion is ironic, as love is typically associated with life and vitality. |

| Metaphor | “The invisible worm” | The worm represents corruption, deceit, or hidden forces that harm the rose. |

| Meter | Iambic dimeter | The poem primarily uses a two-beat rhythm, which creates a sing-song quality and enhances its simplicity. |

| Mood | Throughout the poem | The mood is ominous and melancholic, reflecting themes of decay and destruction. |

| Personification | “O Rose thou art sick” | The rose is given human qualities, such as the ability to be “sick,” emphasizing its symbolic role. |

| Repetition | “Dark secret love” | The emphasis on “dark” underscores the harmful nature of the love described. |

| Rhyme Scheme | “Worm” / “storm” | The poem follows an ABAB rhyme scheme, lending it a rhythmic and lyrical quality. |

| Symbolism | “Rose” | The rose symbolizes love, beauty, or innocence, while its sickness suggests corruption or decay. |

| Synecdoche | “Bed of crimson joy” | The “bed” represents the entirety of love, intimacy, and vulnerability, focusing on one aspect to symbolize the whole. |

| Theme | Corruption of innocence | The central theme explores how hidden forces or secrecy can destroy purity and beauty. |

| Tone | Ominous and foreboding | The tone is created through the use of dark imagery and diction, such as “invisible worm” and “howling storm.” |

| Visual Imagery | “Crimson joy” | Evokes a vivid picture of passionate love, contrasting with the destructive consequences implied. |

| Wordplay | “Invisible worm” | The phrase plays on the idea of invisibility, suggesting both a literal unseen force and metaphorical hidden corruption. |

Themes: “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

1. The Corruption of Innocence: In “The Sick Rose,” Blake explores the theme of innocence being corrupted by hidden or external forces. The rose, a symbol of purity and love, is afflicted by the “invisible worm,” which represents deceit, guilt, or a destructive influence. The phrase “dark secret love” implies a hidden or forbidden force that undermines the rose’s vitality, transforming its joy into sickness and decay. This theme reflects Blake’s broader critique of the loss of innocence, often associated with the transition from a state of natural purity to one marred by societal or emotional corruption. The rose’s “sickness” is not overt but rather insidious, suggesting that innocence is often eroded in ways that are difficult to detect until the damage is irreparable.

2. The Duality of Love and Destruction: Blake highlights the paradoxical nature of love, portraying it as both a source of joy and a force capable of destruction. The “crimson joy” of the rose’s bed suggests passion and vitality, but this very joy becomes the site of its demise. The “dark secret love” of the worm is destructive, emphasizing how love, when tainted by secrecy or possessiveness, can lead to harm rather than fulfillment. The worm’s actions in the “howling storm” underline the tumultuous and chaotic aspects of love, illustrating how it can destabilize and erode even the most beautiful and vibrant elements of life.

3. The Inevitability of Decay: The theme of decay pervades the poem, with the rose’s sickness serving as a metaphor for the inevitable decline of beauty, love, or innocence. The “invisible worm” is a persistent force that operates unseen, symbolizing the natural or existential factors that lead to deterioration over time. Blake’s use of imagery like the “howling storm” reinforces the relentless, uncontrollable nature of these forces. This theme suggests that decay is not always caused by external, visible events but often by internal, hidden factors that undermine strength and vitality gradually.

4. The Danger of Secrecy and Concealment: Blake critiques the destructive power of secrecy in relationships or human interactions. The “invisible worm” thrives in darkness, hidden from view, and its “dark secret love” destroys the rose’s life. This secrecy, whether representing hidden desires, deceit, or suppressed emotions, becomes the catalyst for the rose’s downfall. By emphasizing the clandestine nature of the worm’s actions, Blake warns against the dangers of concealing truth or emotions, which can fester and lead to irreversible harm. This theme reflects a broader moral lesson about the importance of transparency and honesty in maintaining health—whether in love, life, or society.

Literary Theories and “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

| Literary Theory | Application to “The Sick Rose” | References from the Poem |

| Psychoanalytic Theory | Explores the unconscious desires and fears symbolized in the poem. The “invisible worm” can represent repressed guilt, lust, or a hidden destructive force in the psyche. | The “dark secret love” reflects hidden desires, and the “invisible worm” symbolizes unconscious forces at work. |

| Feminist Theory | Examines the role of the rose as a feminine symbol and the worm as a patriarchal or invasive force. This reading critiques the dynamic of domination and vulnerability. | The rose’s “bed of crimson joy” is intruded upon and destroyed by the worm, suggesting exploitation or violation. |

| Ecocriticism | Analyzes the poem as an allegory of nature’s vulnerability to external destruction. The rose symbolizes the natural world, and the worm represents ecological degradation. | The imagery of the “sick” rose and the destructive “invisible worm” illustrates nature being corrupted by human actions or external forces. |

| Deconstruction | Highlights the inherent contradictions and ambiguities in the poem, such as the juxtaposition of “crimson joy” and “dark secret love.” This theory explores how language destabilizes meaning. | The rose is both beautiful and sick, joy is intertwined with destruction, and love is both passionate and harmful. |

Critical Questions about “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

1. How does Blake use symbolism to convey the central themes of the poem?

Blake employs powerful symbols to articulate the themes of corruption, decay, and love’s duality. The rose, traditionally a symbol of beauty and love, is described as “sick,” representing the fragility of innocence and purity when exposed to hidden or destructive forces. The “invisible worm” acts as a metaphor for secretive and corrupting influences, such as deceit, guilt, or forbidden desires. Its actions—finding the rose’s “bed of crimson joy”—depict the intrusion of destructive forces into intimate, sacred spaces. This juxtaposition of the rose’s beauty and the worm’s destructive nature underscores the paradoxical coexistence of love and harm, a recurring theme in Blake’s work.

2. What is the significance of the “dark secret love” in the poem?

The phrase “dark secret love” encapsulates the destructive power of hidden or repressed emotions. This “love” is not nurturing or life-affirming but harmful and clandestine, suggesting a force that operates in secrecy and thrives on concealment. The “dark” nature of this love contrasts sharply with the rose’s vibrant and open beauty, symbolizing how hidden desires or forbidden actions can corrupt what is pure. This idea reflects broader existential concerns about how secrecy and dishonesty can erode trust and integrity, leading to inevitable decay or destruction.

3. How does the imagery in the poem enhance its tone and mood?

Blake’s use of imagery creates a tone of foreboding and a mood of melancholy. Phrases like “howling storm” and “invisible worm” evoke an ominous and chaotic atmosphere, suggesting forces of destruction that are both powerful and elusive. The vivid imagery of the “bed of crimson joy” contrasts with the darker elements, highlighting the fragility and transience of beauty and happiness. These contrasts between light and dark, joy and destruction, enhance the emotional depth of the poem, making its warnings about corruption and decay resonate more strongly.

4. In what ways does the poem reflect Blake’s broader critique of societal or moral decay?

“The Sick Rose” can be interpreted as a microcosm of Blake’s larger critique of societal or moral decay. The rose’s sickness symbolizes the corruption of innocence and beauty, which Blake often associates with industrialization, rigid societal norms, and moral hypocrisy. The “invisible worm” might represent the hidden forces of exploitation or repression that undermine the natural order. By portraying this decay as secretive and insidious, Blake critiques not only overt acts of harm but also the subtle, systemic forces that corrupt society and the individual. The poem’s stark simplicity allows these themes to resonate universally.

Literary Works Similar to “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

- “Ode to a Nightingale” by John Keats

This poem explores the interplay between beauty and mortality, reflecting on the transient nature of joy and life, themes that parallel Blake’s portrayal of the rose’s sickness and decay. - “To the Daffodils” by Robert Herrick

Herrick’s poem focuses on the fleeting nature of beauty and existence, echoing Blake’s use of the rose as a symbol of innocence and vitality that is inevitably lost. - “A Poison Tree” by William Blake

Another poem by Blake, it similarly examines the destructive potential of suppressed emotions, such as anger, which parallels the “dark secret love” that destroys the rose in The Sick Rose. - “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson

This poem delves into themes of mortality and the unseen forces that govern the end of life, akin to the invisible worm in Blake’s work that symbolizes hidden destruction. - “The Darkling Thrush” by Thomas Hardy

Hardy’s poem aligns with The Sick Rose through its melancholic tone and the symbolic use of nature to explore themes of despair, decay, and the passage of time.

Representative Quotations of “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “O Rose thou art sick.” | Introduces the central metaphor of the rose as a symbol of love, beauty, or innocence that is corrupted. | Psychoanalytic Theory: The sickness represents unconscious fears, desires, or hidden trauma. |

| “The invisible worm,” | Refers to a destructive, unseen force that harms the rose. | Ecocriticism: The worm symbolizes hidden ecological threats or human interference with nature. |

| “That flies in the night” | Highlights the stealthy, secretive nature of the worm’s actions. | Deconstruction: Suggests the ambiguity and instability of meaning—night as a metaphor for secrecy or ignorance. |

| “In the howling storm:” | Evokes chaos and violence, emphasizing the destructive environment. | Feminist Theory: Could symbolize external forces of patriarchy or oppression disrupting natural harmony. |

| “Has found out thy bed” | Suggests intrusion into an intimate or sacred space. | Psychoanalytic Theory: The bed symbolizes vulnerability, intimacy, or the subconscious. |

| “Of crimson joy:” | Refers to passion or vitality, which is juxtaposed with corruption and decay. | Marxist Theory: May symbolize the exploitation of pure joy or love for selfish gains, reflecting societal imbalances. |

| “And his dark secret love” | Indicates hidden or forbidden desires that are harmful. | Psychoanalytic Theory: Represents repressed or taboo emotions that lead to internal conflict. |

| “Does thy life destroy.” | Concludes with the total corruption and destruction of innocence. | Moral Criticism: Reflects on the consequences of hidden immorality or unchecked desires. |

| “Rose” | Symbolizes purity, beauty, or feminine qualities, often in contrast with its sickness. | Feminist Theory: Interpreted as the feminine subject, victimized by external forces. |

| “Invisible worm” | Acts as a metaphor for secrecy, guilt, or corruption that operates unseen. | Ecocriticism: Highlights human neglect of hidden forces impacting the natural world, or Deconstruction: Challenges the binary of visibility and invisibility in symbolism. |

Suggested Readings: “The Sick Rose” by William Blake

- McQuail, Josephine A. “Passion and Mysticism in William Blake.” Modern Language Studies, vol. 30, no. 1, 2000, pp. 121–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3195433. Accessed 3 Jan. 2025.

- Gleckner, Robert F. “William Blake and the Human Abstract.” PMLA, vol. 76, no. 4, 1961, pp. 373–79. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/460620. Accessed 3 Jan. 2025.

- BERWICK, J. F. “THE SICK ROSE: A SECOND OPINION.” Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, no. 47, 1976, pp. 77–81. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41801610. Accessed 3 Jan. 2025.

- Brown, Cory. “The Sick Rose: Some Problems with the Self.” Writing on the Edge, vol. 28, no. 2, 2018, pp. 41–52. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26808983. Accessed 3 Jan. 2025.