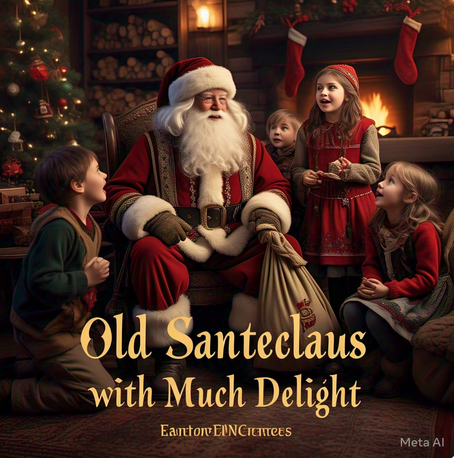

Introduction: “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

“Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich first appeared in the late 19th century, likely in a collection of his poems celebrating holiday themes and childhood innocence. The poem captures the whimsical spirit of Christmas through the character of Kriss Kringle, a traditional representation of Santa Claus. Aldrich paints a vivid and charming scene where Kriss Kringle, having filled children’s stockings with gifts, notices an empty oriole’s nest high in a tree. With playful humor, he likens it to a stocking and, in a lighthearted gesture, drops a handful of snowflakes into it. This blend of warmth, imagination, and humor contributes to the poem’s enduring popularity, as it highlights the joy and generosity associated with Christmas while also embodying Aldrich’s signature wit. The poem’s appeal lies in its simple yet evocative imagery and its ability to capture the magic of childhood wonder, making it a beloved holiday verse.

Text: “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

Just as the moon was fading

Amid her misty rings,

And every stocking was stuffed

With childhood’s precious things,

Old Kriss Kringle looked around,

And saw on the elm-tree bough,

High hung, an oriole’s nest,

Lonely and empty now.

“Quite a stocking,” he laughed,

“Hung up there on a tree!

I didn’t suppose the birds

Expected a present from me!”

Then old Kriss Kringle, who loves

A joke as well as the best,

Dropped a handful of snowflakes

Into the oriole’s empty nest.

Annotations: “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

| Line from Poem | Simple Explanation | Literary Devices |

| Just as the moon was fading | The moon was disappearing in the sky. | Imagery (visual), Personification (moon “fading”) |

| Amid her misty rings, | The moon was surrounded by misty clouds. | Personification (moon described as “her”), Imagery |

| And every stocking was stuffed | Every Christmas stocking was filled with gifts. | Imagery (tactile – “stuffed stockings”) |

| With childhood’s precious things, | The gifts were special to children. | Emotive Language (evokes nostalgia and innocence) |

| Old Kriss Kringle looked around, | Santa Claus (Kriss Kringle) looked around. | Characterization (Kriss Kringle as a joyful figure) |

| And saw on the elm-tree bough, | He noticed something on the branch of an elm tree. | Imagery (visual), Symbolism (tree as nature’s stocking) |

| High hung, an oriole’s nest, | He saw a bird’s nest high up in the tree. | Symbolism (nest as a stocking) |

| Lonely and empty now. | The nest was empty because the birds had left. | Personification (“lonely”), Imagery (emptiness) |

| “Quite a stocking,” he laughed, | He joked that the nest looked like a Christmas stocking. | Metaphor (nest compared to stocking), Humor |

| “Hung up there on a tree! | The nest was positioned high up like a stocking hanging. | Visual Imagery |

| I didn’t suppose the birds | He jokingly suggests birds wouldn’t expect gifts. | Anthropomorphism (giving birds human expectations) |

| Expected a present from me!” | He jokes that birds don’t wait for gifts like children do. | Irony (unexpected comparison of birds to children) |

| Then old Kriss Kringle, who loves | Kriss Kringle is known for his playful and kind nature. | Characterization |

| A joke as well as the best, | He enjoys humor just like anyone else. | Simile (“as well as the best”) |

| Dropped a handful of snowflakes | He playfully put snowflakes in the nest as a “gift.” | Imagery (tactile – “handful of snowflakes”) |

| Into the oriole’s empty nest. | The nest, instead of holding eggs, now held snowflakes. | Symbolism (snowflakes as a lighthearted gift) |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

| Literary Device | Example from Poem | Explanation |

| Allusion | “Kriss Kringle” | Refers to Santa Claus, a well-known Christmas figure. |

| Anthropomorphism | “I didn’t suppose the birds expected a present from me!” | The birds are given human-like expectations, as if they are children waiting for gifts. |

| Assonance | “old Kriss Kringle looked around” | The repetition of the “o” sound enhances the lyrical quality. |

| Characterization | “Then old Kriss Kringle, who loves a joke as well as the best” | Depicts Kriss Kringle as humorous and kind-hearted. |

| Contrast | “Every stocking was stuffed / Lonely and empty now.” | The fullness of the stockings contrasts with the emptiness of the nest. |

| Emotive Language | “childhood’s precious things” | Evokes nostalgia and warmth associated with childhood and Christmas. |

| Humor | “I didn’t suppose the birds expected a present from me!” | A playful remark, as birds don’t expect Christmas gifts. |

| Hyperbole | “Quite a stocking, he laughed, hung up there on a tree!” | Exaggeration of the nest as if it were a real Christmas stocking. |

| Imagery (Visual) | “Just as the moon was fading amid her misty rings” | Creates a vivid picture of the night sky. |

| Imagery (Tactile) | “Dropped a handful of snowflakes” | Describes the feeling of cold snowflakes in one’s hand. |

| Irony | “I didn’t suppose the birds expected a present from me!” | It’s ironic because birds don’t receive Christmas gifts like children do. |

| Metaphor | “Quite a stocking” | The nest is metaphorically compared to a Christmas stocking. |

| Mood | “childhood’s precious things” | The mood is warm, nostalgic, and festive. |

| Onomatopoeia | “laughed” | The word imitates the sound of laughter, adding to the joyful tone. |

| Personification | “Just as the moon was fading amid her misty rings” | The moon is given human-like qualities as if it is “fading” intentionally. |

| Play on Words (Pun) | “Quite a stocking” | A humorous pun, as a bird’s nest is compared to a Christmas stocking. |

| Repetition | “Old Kriss Kringle looked around” | The phrase “Kriss Kringle” is repeated to emphasize his presence. |

| Simile | “A joke as well as the best” | A comparison using “as” to show that Kriss Kringle enjoys jokes just like anyone else. |

| Symbolism | “oriole’s empty nest” | The empty nest symbolizes abandonment or the passing of seasons, contrasting with the fullness of children’s stockings. |

Themes: “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

- Nostalgia and Childhood Innocence

- Thomas Bailey Aldrich beautifully captures the nostalgia and innocence of childhood Christmas memories in “Kriss Kringle.” The poem’s opening lines—“Just as the moon was fading / Amid her misty rings”—create a peaceful and reflective mood, evoking the quiet magic of Christmas Eve. The mention of stockings being “stuffed / With childhood’s precious things” emphasizes the joy and excitement that children feel during the holiday season. Aldrich, writing in the late 19th century, portrays Christmas as a time of warmth, tradition, and pure happiness, highlighting how childhood is filled with simple yet meaningful pleasures. By focusing on youthful wonder and holiday excitement, the poem taps into universal nostalgia, making it a timeless celebration of the Christmas spirit.

- Humor and Playfulness

- Aldrich infuses “Kriss Kringle” with lighthearted humor, portraying Santa Claus as a mischievous and jovial figure. Kriss Kringle notices an oriole’s empty nest high in a tree and playfully compares it to a Christmas stocking, remarking, “Quite a stocking,” he laughed, “Hung up there on a tree!” His humorous observation—“I didn’t suppose the birds / Expected a present from me!”—adds an amusing twist, as if nature, like children, also anticipates gifts. This joke, along with his playful act of dropping snowflakes into the nest, showcases Santa’s good-natured humor and whimsical spirit. Aldrich’s use of comedy and wordplay reflects the fun and joy that come with Christmas, making the poem both entertaining and heartwarming for readers of all ages.

- Nature and the Intersection of Human Festivity

- In “Kriss Kringle,” Thomas Bailey Aldrich intertwines the themes of nature and holiday festivity, using the oriole’s nest as a symbol of change and contrast. The poem presents a world where human traditions and nature coexist, with the moon’s fading light and the wintery atmosphere setting a seasonal backdrop for Kriss Kringle’s visit. The empty oriole’s nest, described as “Lonely and empty now,” contrasts with the full and joyous stockings of children, symbolizing the passage of time and the cyclical nature of life. By comparing the nest to a stocking, Aldrich humorously suggests that even the natural world might partake in the holiday spirit. This interplay between festivity and nature highlights how Christmas magic is not limited to homes and stockings but extends into the world around us, making the poem both whimsical and reflective.

- The Spirit of Generosity and Unexpected Delight

- A central theme in “Kriss Kringle” is the joy of giving, illustrated by Kriss Kringle’s act of filling the empty nest with snowflakes. Even after ensuring that every stocking is filled, he extends his generosity beyond human traditions, noticing the nest and whimsically offering it a “gift” of snowfall. Though this is not a traditional present, it symbolizes the simple yet meaningful nature of giving, showing that generosity does not always have to be extravagant. Aldrich, writing in the late 19th century, reflects on the idea that Christmas spirit is found in small, thoughtful gestures, and joy can come from unexpected moments of kindness and humor. The poem suggests that even nature, in its quiet and unassuming way, can be part of the season’s giving and receiving, reinforcing the timeless message that kindness, no matter how small, is always a gift worth sharing.

Literary Theories and “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

| Literary Theory | Application to “Kriss Kringle” | References from the Poem |

| Formalism (Close Reading) | Focuses on the poem’s structure, style, and literary devices. Analyzes imagery, metaphor, and personification used to create a vivid Christmas scene. | – The metaphor comparing the oriole’s nest to a stocking (“Quite a stocking,” he laughed, “Hung up there on a tree!”) emphasizes the playful mood. – Personification of the moon (“Just as the moon was fading / Amid her misty rings”) gives a dreamy, magical quality to the setting. |

| Reader-Response Theory | Examines how different readers might interpret the poem based on their experiences, emotions, and cultural background. A child may see it as a fun holiday story, while an adult might view it as nostalgic. | – A child may enjoy Kriss Kringle’s humor (“I didn’t suppose the birds / Expected a present from me!”) as a fun joke. – An older reader might connect with the nostalgic tone of “childhood’s precious things,” evoking memories of their own Christmas experiences. |

| New Historicism | Explores how the poem reflects the 19th-century American Christmas traditions and social values. During Aldrich’s time, Christmas was becoming more commercialized but still retained a strong emphasis on family, innocence, and nature. | – The poem presents a romanticized version of Santa Claus, aligning with the 19th-century ideal of Christmas as a time of joy and giving. – The reference to stockings and Kriss Kringle mirrors Victorian-era Christmas customs, where stockings were filled with small gifts for children. |

| Ecocriticism | Focuses on the relationship between nature and human culture, analyzing how nature is represented in literature. The poem portrays nature as both part of and separate from human traditions. | – The oriole’s empty nest symbolizes the natural cycle of life and seasonal changes (“Lonely and empty now.”). – Kriss Kringle interacts with nature in a playful way, dropping snowflakes into the nest, suggesting a lighthearted harmony between humanity and the natural world. |

Critical Questions about “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

- How does “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich use humor to convey the spirit of Christmas?

- “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich employs lighthearted humor to reinforce the joyful and playful nature of Christmas. The poem presents Santa Claus not just as a giver of gifts but also as someone who enjoys a joke. This is evident in Kriss Kringle’s reaction to the oriole’s nest, which he humorously compares to a Christmas stocking, exclaiming, “Quite a stocking,” he laughed, “Hung up there on a tree!” His amusing remark about birds expecting gifts—“I didn’t suppose the birds / Expected a present from me!”—adds a playful contrast between human traditions and nature’s indifference to holiday customs. This comedic perspective makes Kriss Kringle feel more relatable and emphasizes the lighthearted essence of Christmas celebrations. Aldrich, writing in the late 19th century, captured the growing sentimental and festive view of Santa Claus, which became increasingly prominent in American holiday traditions. The humor in the poem contributes to the warmth and delight associated with Christmas, making it a charming and enduring holiday piece.

- What role does nature play in “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich, and how does it interact with the holiday theme?

- Nature plays a symbolic and contrasting role in “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich, highlighting the difference between human festivity and the natural world’s seasonal cycles. While the poem begins by describing a traditional Christmas Eve scene, filled with stockings and childhood joy, it soon shifts to Kriss Kringle’s discovery of an oriole’s empty nest high in an elm tree. The nest, described as “Lonely and empty now,” contrasts sharply with the full stockings indoors, symbolizing the passage of time and the changing seasons. Unlike human traditions, which repeat year after year, nature follows its own course, with birds migrating and their nests left behind. Yet, Kriss Kringle acknowledges nature with a playful gift of snowflakes, demonstrating that the magic of Christmas can extend beyond human spaces. Written in the late 19th century, when literature often romanticized nature, Aldrich’s poem reflects a gentle harmony between the natural world and festive traditions, showing how the spirit of Christmas can exist in unexpected places.

- How does “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich reflect 19th-century Christmas traditions and values?

- “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich reflects 19th-century Christmas traditions through its depiction of Santa Claus, gift-giving, and the importance of joy and generosity. The poem begins with the familiar image of stockings “stuffed / With childhood’s precious things,” emphasizing how Christmas was a time centered on children’s happiness and wonder. During the Victorian era, Christmas traditions, including stockings, decorated trees, and Santa Claus (also known as Kriss Kringle), were becoming more widespread, popularized by writers such as Clement Clarke Moore and Charles Dickens. Aldrich’s poem mirrors this evolving cultural depiction of Christmas, portraying Santa as a kind and humorous figure rather than a solemn or mystical one. Additionally, the idea of giving even the smallest gifts, like snowflakes to an empty nest, reflects the 19th-century emphasis on generosity and goodwill. At a time when Christmas was transitioning into a more family-centered, joyful celebration, “Kriss Kringle” serves as a reflection of those evolving values.

- What is the significance of Kriss Kringle’s act of dropping snowflakes into the oriole’s nest in “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich?

- The act of dropping snowflakes into the oriole’s nest in “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich is both symbolic and humorous, reinforcing the poem’s themes of generosity, playfulness, and seasonal change. While Kriss Kringle is known for delivering meaningful presents to children, his action here is purely whimsical and unexpected. The nest, described as “Lonely and empty now,” symbolizes absence, migration, or the passage of time, while the snowflakes serve as a lighthearted “gift” that fills the emptiness in a fleeting but charming way. This moment captures the idea that giving does not always have to be extravagant—sometimes, even the smallest gestures carry meaning. The scene also highlights Kriss Kringle’s playful nature, as he enjoys the irony of treating the nest like a stocking. Given that Aldrich wrote during the late 19th century, a period when literature often emphasized nostalgia and sentimental themes, the action reflects both a celebration of the season’s joy and a humorous acknowledgment of nature’s indifference to human traditions. Ultimately, the snowflakes serve as a reminder that generosity and holiday spirit can take many forms, even in unexpected places.

Literary Works Similar to “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

- “A Visit from St. Nicholas“ (commonly known as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”) by Clement Clarke Moore – Similar in theme and tone, this poem also depicts Santa Claus (St. Nicholas) in a joyful and magical Christmas setting, emphasizing childhood wonder and tradition.

- “The Christmas Holly” by Eliza Cook – This poem shares a festive and nature-infused theme, celebrating the spirit of Christmas through vivid imagery of holly and winter landscapes, much like Aldrich’s use of nature in his poem.

- “Christmas Bells” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow – Though slightly more solemn in tone, this poem explores Christmas joy and tradition, mirroring the themes of seasonal change, holiday spirit, and reflection found in “Kriss Kringle.”

- “A Christmas Carol” by James Russell Lowell – This poem, like Aldrich’s, embraces the joy, generosity, and charm of Christmas, blending a warmhearted tone with seasonal imagery and a focus on kindness.

Representative Quotations of “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “Just as the moon was fading / Amid her misty rings,” | Describes the peaceful Christmas Eve setting, creating a dreamy and magical atmosphere. | Formalism – Focuses on imagery and poetic structure to evoke a sense of wonder and tranquility. |

| “And every stocking was stuffed / With childhood’s precious things,” | Highlights the tradition of filling stockings with gifts, symbolizing childhood joy. | Reader-Response Theory – Evokes nostalgia and personal connections to holiday traditions. |

| “Old Kriss Kringle looked around, / And saw on the elm-tree bough,” | Introduces Santa Claus as an observant and playful character who notices the world around him. | New Historicism – Reflects 19th-century depictions of Santa Claus and the rise of Christmas traditions. |

| “High hung, an oriole’s nest, / Lonely and empty now.” | The empty bird’s nest contrasts with the full stockings, symbolizing seasonal change and the passage of time. | Ecocriticism – Explores the relationship between nature and human celebration. |

| “Quite a stocking,” he laughed, / “Hung up there on a tree!” | Kriss Kringle humorously compares the bird’s nest to a Christmas stocking, showing his playful nature. | Structuralism – Examines symbolic associations between objects (nest as a stocking) and their meanings. |

| “I didn’t suppose the birds / Expected a present from me!” | Kriss Kringle’s joke highlights the contrast between human traditions and nature’s indifference to Christmas customs. | Reader-Response Theory – Allows readers to interpret the humor based on their own perspectives on Christmas and nature. |

| “Then old Kriss Kringle, who loves / A joke as well as the best,” | Establishes Santa Claus as a lighthearted and cheerful figure, reinforcing the festive mood. | New Historicism – Reflects the evolving portrayal of Santa as a kind and humorous character in 19th-century literature. |

| “Dropped a handful of snowflakes / Into the oriole’s empty nest.” | A whimsical act where Kriss Kringle “fills” the empty nest, reinforcing the theme of generosity and playfulness. | Marxist Criticism – Suggests that giving does not have to be materialistic, as even small gestures can hold meaning. |

| “Lonely and empty now.” | Highlights the contrast between the joyful, filled stockings and the abandoned nest, symbolizing different experiences of the season. | Formalism – Uses contrast to emphasize themes of abundance versus emptiness. |

| “Who loves / A joke as well as the best,” | Reinforces Kriss Kringle’s playful and joyful personality, showing that humor is part of the Christmas spirit. | Psychoanalytic Criticism – Explores Santa Claus as a figure of childlike joy and humor, appealing to the subconscious desire for play and happiness. |

Suggested Readings: “Kriss Kringle” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

- Aldrich, Thomas Bailey. The Poems of Thomas Bailey Aldrich. Houghton, Mifflin, 1907.

- WATSON, KATHERINE W. “Christmas-Tide in Poetry.” The Elementary English Review, vol. 6, no. 10, 1929, pp. 264–68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41381283. Accessed 20 Mar. 2025.