Introduction: “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

“Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber first appeared in 2017 in contemporary online poetry circles and later circulated widely in collections of Arab-American diasporic writing, where it gained recognition for its innovative linguistic experimentation. The poem’s popularity stems from its deliberate distortion of English syntax to mimic the struggling, intimate, intergenerational voice of an Arabic speaker—most powerfully captured in lines such as “oh teita, the language the english no it understand tongue of you” and “i try and i fail to fit languages of us in each other.” Jaber’s central idea revolves around the impossibility of fully translating love, memory, and heritage across linguistic borders, a theme heightened by the poem’s recursive attempts to make English “fit” the emotional grammar of Arabic. The speaker’s yearning for ancestral continuity—reflected in images like “i split open face of me with spoon” and the haunting closure, “soil of the grave falls it without grace from lips of me”—resonated with readers navigating diasporic identity, linguistic loss, and familial longing. It is this fusion of experimental form, cultural memory, and emotional vulnerability that propelled the poem to its acclaimed status within modern Arab-American literature.

Text: “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

oh teita, the language the english no it understand tongue of you. and no can i

i feed you these the morsels from mouth of me. language of me the arabic half-

chewed. oh teita, let me i try and i fail to fit languages of us in each other.

seen i face of you split open by riot laughter. the spit it falls without grace from

lips of you thins. complexion of you light; skin of you wrinkled but healthy;

flecks olive they try to jump from folds of the corners of the eyes of you. can i

find in the mirror eyelids of you the heavy. eyelashes of you. the echo of the

nose of you. sometimes, i split open face of me with spoon, tool blunt &

wrong. i want from you for you to bleed from in me into the sink, so that can i i

ask these the questions sprinkled you in lungs of me. i cough out them, always

in the time the wrong. i laugh. soil of the grave falls it without grace from lips

of me.

Copyright © 2017 Noor Jaber. Used with permission of the author.

Annotations: “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

| Text (Line / Segment) | Annotation / Meaning | Devices Used |

| “oh teita, the language the english no it understand tongue of you. and no can i” | The speaker addresses her grandmother (“teita”), exposing the tension between Arabic and English. The broken grammar enacts linguistic struggle. | 💬 Apostrophe, 🌐 Hybrid Syntax, 🧩 Broken Grammar, ⚡ Internal Conflict, ➰ Enjambment |

| “i feed you these the morsels from mouth of me.” | Language as nourishment—communication imagined like feeding, implying tenderness mixed with difficulty. | 🔥 Metaphor, 🎨 Imagery, ✨ Symbolism, 🧩 Fragmentation |

| “language of me the arabic half-chewed.” | Suggests translation as something incomplete, partially digested, and not ready for full consumption. | 🔥 Metaphor, ✨ Symbolism, 🌐 Hybrid Syntax, 🧩 Broken Grammar |

| “oh teita, let me i try and i fail to fit languages of us in each other.” | A confession of failure in merging Arabic and English; highlights intergenerational linguistic distance. | 💬 Apostrophe, ⚡ Internal Conflict, 🧩 Fragmentation, 🌐 Hybrid Syntax, 🔁 Repetition (“I”) |

| “seen i face of you split open by riot laughter.” | Vivid and violent juxtaposition—joy described through imagery of splitting/opening. | 🎨 Imagery, 💥 Violence Imagery, ➰ Enjambment |

| “the spit it falls without grace from lips of you thins.” | Bodily detail emphasizes intimacy and decay; loss of “grace” suggests aging. | 🫁 Body Imagery, 🎨 Imagery, ✨ Symbolism, 🧩 Broken Grammar |

| “complexion of you light; skin of you wrinkled but healthy;” | Observing aging lovingly; the syntax mimics Arabic possessive structure. | 🎨 Imagery, 🌐 Hybrid Syntax, ✨ Symbolism |

| “flecks olive they try to jump from folds of the corners of the eyes of you.” | Eye color becomes animated—heritage trying to “jump out,” symbolizing ancestry. | 🎨 Imagery, ✨ Symbolism, 🔥 Metaphor |

| “can i find in the mirror eyelids of you the heavy. eyelashes of you. the echo of the nose of you.” | The speaker searches herself for her grandmother’s features—identity through inheritance. | 🎨 Imagery, 🫁 Body Imagery, ✨ Symbolism, 🧩 Fragmentation |

| “sometimes, i split open face of me with spoon, tool blunt & wrong.” | Self-harm metaphor for excavating identity; the spoon symbolizes inadequate tools of translation/culture. | 💥 Violence Imagery, 🔥 Metaphor, ✨ Symbolism, ⚡ Internal Conflict |

| “i want from you for you to bleed from in me into the sink,” | Desire for direct transfer of heritage—intense, visceral image. | 💥 Violence Imagery, 🫁 Body Imagery, 🎨 Imagery, 🔥 Metaphor |

| “so that can i i ask these the questions sprinkled you in lungs of me.” | Questions “sprinkled” in lungs symbolize inherited language/ancestry embedded in breathing. | 🫁 Body Imagery, ✨ Symbolism, 🔁 Repetition, 🧩 Hybrid Grammar |

| “i cough out them, always in the time the wrong.” | Coughing out questions = struggling to express oneself at the right moment. | 🔥 Metaphor, 🫁 Body Imagery, 🎭 Tone Shift, 🌐 Hybrid Syntax |

| “i laugh. soil of the grave falls it without grace from lips of me.” | Death and ancestry mingle with speech; “soil of the grave” symbolizes inherited trauma/history. | ✨ Symbolism, 🎨 Imagery, 💥 Violence Imagery, 🧩 Broken Grammar, ➰ Enjambment |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

| Device | Example from Poem | Explanation |

| Code-switching / Language Interference | “the language the english no it understand tongue of you” | English is shaped by Arabic syntax to show linguistic struggle and heritage. |

| Anaphora | Repetition of “of you” | Repeated structure emphasizes affection and longing for teita. |

| Syntax Disruption | “let me i try and i fail” | Verb–subject reversal imitates Arabic grammar, dramatizing translation difficulty. |

| Address (Apostrophe) | “oh teita” | Directly addressing grandmother creates intimacy and emotional immediacy. |

| Imagery | “spit it falls without grace from lips of you” | Vivid bodily imagery conveys aging, tenderness, and realism. |

| Repetition | “can i… can i” | Shows the speaker’s yearning and hesitation across generations. |

| Personification | “flecks olive they try to jump” | Human-like action deepens cultural symbolism of olive (heritage). |

| Metaphor | “split open face of me with spoon” | Expresses painful self-examination and identity excavation. |

| Symbolism | “soil of the grave” | Symbol of ancestry, mortality, and generational continuity. |

| Enjambment | Lines break mid-idea | Mimics breathlessness and linguistic fragmentation. |

| Internal Conflict | “i try and i fail to fit languages of us in each other” | Reveals emotional tension between belonging and linguistic impossibility. |

| Cultural Imagery | “olive… folds of the corners of the eyes of you” | Olive symbolizes Middle Eastern heritage and memory. |

| Tone Shifting | From tender → dark (“soil of the grave…”) | Moves from affection to mourning, reflecting diaspora trauma. |

| Alliteration | “face… split open… spoon” | Repeated ‘s’ sounds create softness yet pain. |

| Motif of the Body | “lips of you,” “eyelids of you,” “lungs of me” | The body becomes a site of memory and inherited identity. |

| Paradox | “laugh… falls it without grace” | Joy blends with loss, showing complex emotional states. |

| Juxtaposition | “riot laughter” vs. “soil of the grave” | Life and death placed together to show generational fragility. |

| Stream-of-Consciousness | Loose, flowing syntax | Captures emotional overflow and unfiltered thought. |

| Themes of Death & Legacy | “soil of the grave falls… from lips of me” | Death becomes part of identity formation and inheritance. |

| Emotional Imagery (Pathos) | “i cough out them… always in the time the wrong” | The guilt of imperfect communication evokes emotional resonance. |

Themes: “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

🔶 • Theme 1: Language as Inheritance and Burden

“Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber foregrounds language not merely as a communicative tool but as an inherited, almost bodily legacy that carries emotional, cultural, and intergenerational weight. The poem dramatizes the impossibility of fully transferring Arabic grammar and sensibilities into the structural constraints of English; consequently, the speaker’s fractured syntax becomes both a performative enactment of linguistic burden and a symbol of an identity caught between two grammars that refuse full reconciliation. Through images of “half-chewed Arabic,” “morsels,” and “lungs sprinkled with questions,” language becomes a substance consumed, breathed, and expelled, making it inseparable from bodily existence. Yet this inheritance is equally a burden—one that the speaker feels compelled to preserve, even as the task of translating it demands emotional labour, vulnerability, and an acknowledgment of persistent inadequacy embedded within diasporic linguistic experience.

🟣 • Theme 2: Intergenerational Memory and the Body

“Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber explores how memory is preserved and transmitted through the body, especially in the context of familial lineage. The speaker attempts to locate her grandmother not through stories alone but through features—eyelids, nose, olive flecks—embedded in her own reflection, as though memory has been literally inscribed on flesh. The poem’s bodily metaphors—spit, lungs, blood, face splitting—suggest that ancestry circulates internally like oxygen, making the past not abstract but physically inhabiting the present. Intergenerational memory becomes tactile and visceral, experienced through wrinkles, skin, and breath; thus, the body becomes an archive that resists erasure. The grandmother’s presence survives in textures, gestures, and the speaker’s corporeal attempts to excavate meaning, even when linguistic articulation fails. In this way, memory persists not through perfected grammar but through inherited bodily resonances that refuse to fade.

🟢 • Theme 3: Diasporic Fragmentation and the Struggle to Belong

“Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber powerfully dramatizes the fragmentation inherent in diasporic subjectivity, where belonging becomes unstable, partial, and fractured across two linguistic worlds. The poem’s broken syntax, shifting pronoun positions, and disrupted grammatical patterns embody the speaker’s divided sense of self, as though her identity must be assembled from incompatible linguistic parts. The repeated failures to “fit” Arabic into English expose a broader existential dilemma: the impossibility of complete assimilation without the loss of ancestral identity, and the parallel inability to return fully to origins once displacement has occurred. This fragmentation is not portrayed as mere deficiency but as a lived reality that shapes emotional expression, familial intimacy, and self-perception. Thus, diasporic belonging becomes a liminal space structured by discontinuity, where the speaker negotiates multiple cultural grammars that both sustain and destabilize her sense of home.

🔵 • Theme 4: Violence of Translation and the Desire for Fusion

“Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber employs the imagery of self-harm, bleeding, splitting, and blunt tools to articulate the violence inherent in the act of translation—an effort not simply to convert words but to merge identities, histories, and emotional registers across languages. The speaker’s attempt to “split open” her own face with a “blunt” spoon suggests that translation requires dissecting oneself with inadequate instruments, revealing a painful mismatch between what the body contains and what language permits. The desire for fusion—wanting the grandmother to “bleed into” her—reflects a yearning for an unbroken continuity of heritage that the linguistic gap brutally interrupts. In this sense, translation becomes a site of emotional strain and symbolic violence, where the impossibility of perfect transfer generates wounds rather than seamless cohesion, illuminating the painful limits of language in shaping diasporic identity.

Literary Theories and “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

| Theory | Reference from Poem | Explanation (Application of Theory) |

| 🌍 Postcolonial Theory | “oh teita, the language the english no it understand tongue of you.” | Postcolonial theory highlights linguistic hierarchy and the colonial legacy of English. The poem mimics Arabic syntax within English to resist linguistic domination. The speaker’s inability to “fit languages of us in each other” portrays the tension between colonially imposed language and ancestral identity. |

| 🧬 Diaspora & Identity Theory | “let me i try and i fail to fit languages of us in each other.” | Diaspora studies examine fractured identity, cultural displacement, and generational memory. The poem’s struggle between Arabic and English reflects hybrid identity formation. The speaker’s longing for teita (“i feed you these the morsels… language of me the arabic half-chewed”) symbolizes incomplete inheritance across migration. |

| 🪞 Psychoanalytic Theory | “i split open face of me with spoon… i want… you to bleed from in me.” | Psychoanalytic theory explores subconscious desire, internal conflict, and the formation of self through the Other. Here, the “face of me” and desire to let the grandmother “bleed… into me” reflect deep psychological yearning for unity, identity, and ancestral embedding. |

| 📜 Feminist Theory (Intergenerational Matrilineality) | “seen i face of you split open by riot laughter… eyelashes of you.” | Feminist literary theory emphasizes women’s lived experience, maternal memory, and generational inheritance. The poem centers teita—the grandmother—as the primary source of language, identity, and cultural continuity. Her body (“lips of you,” “eyelids of you”) becomes a repository of history, womanhood, and survival. |

Critical Questions about “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

🔵 Critical Question 1: How does “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber use distorted English syntax to express cultural and linguistic fragmentation?

The deliberate syntactic distortion in “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber becomes a structural embodiment of cultural dislocation, reflecting how hybrid identities often fail to inhabit a single linguistic frame. By producing phrases such as “the language the english no it understand tongue of you,” Jaber transforms English into a textured, resistant space where Arabic grammar intrudes, disrupts, and reshapes meaning. This hybridity mirrors the speaker’s internal fragmentation—the impossibility of fully expressing love, memory, and intergenerational belonging in a language that cannot carry ancestral emotional weight. The poem’s half-translated expressions, like “i try and i fail to fit languages of us in each other,” expose a psychological and cultural tension: English becomes both a tool and a barrier. The syntactic friction thus articulates the speaker’s liminality, reflecting how diasporic subjects live between grammars, histories, and emotional vocabularies.

🟣 Critical Question 2: In what ways does Noor Jaber use the figure of the grandmother to explore intergenerational inheritance and embodied memory in “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English”?

In “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber, the grandmother—teita—functions as both a living archive and a conduit of cultural transmission, her body holding the memories, syntax, and emotional codes that the speaker desperately wishes to preserve. The poem foregrounds her physicality (“eyelids of you,” “olive flecks,” “lips of you”) to emphasize how lineage is not abstract but corporeal, embedded in textures, wrinkles, and gestures. Yet the speaker’s attempt to internalize her grandmother—“i split open face of me with spoon… i want… you to bleed from in me”—reveals an almost desperate longing to inherit what threatens to disappear with generational distance. The grandmother symbolizes a fading linguistic and cultural root, and the speaker’s struggle to “fit languages of us in each other” reflects a profound fear of losing ancestral intimacy. Through her, the poem meditates on memory as both embodied and vulnerable.

🟢 Critical Question 3: How does the poem navigate themes of death, ancestry, and continuity, particularly in its final image of “soil of the grave”? (from “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber)

In “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber, the recurring imagery of the body culminates in the haunting final line: “soil of the grave falls it without grace from lips of me,” a moment that merges ancestry, loss, and linguistic inheritance. The grave soil becomes a metaphor for the weight of lineage the speaker carries, suggesting that the grandmother’s memory—her language, her laughter, her embodied history—has already begun to sediment within the speaker’s consciousness. This image also dramatizes the unavoidable erosion of cultural continuity: as the grandmother ages, the speaker inherits fragments rather than wholeness, symbolized by “the arabic half-chewed” and the cough of misplaced questions. Death thus becomes intertwined with transmission; what is inherited arrives broken, mistranslated, and unstable. The soil signifies both burial and planting, marking the simultaneous loss and preservation at the heart of diasporic identity formation.

🟠 Critical Question 4: How does the poem use bodily imagery to explore the psychological burden of translation and self-formation in “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber?

In “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber, bodily imagery serves as an extended metaphor for the psychological strain of navigating between languages and identities. The speaker’s desire to “split open face of me with spoon” expresses a violent introspection—an attempt to excavate a self that feels fragmented, mistranslated, and incomplete. The grandmother’s body likewise becomes a symbolic landscape: her “riot laughter,” “wrinkled but healthy” skin, and “olive flecks” evoke heritage, resilience, and the emotional weight of belonging. Yet the speaker’s inability to fully absorb her—mirrored in lines like “i feed you these the morsels… language of me the arabic half-chewed”—suggests that translation is not merely linguistic but bodily, enacted through breath, lungs, lips, and inheritance. The poem thus renders the body a site of cultural negotiation, revealing how diasporic subjects bear the weight of identity through flesh, memory, and unspoken emotional labor.

Literary Works Similar to “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

🟣 • “Arabic” by Naomi Shihab Nye

Similarity: Like Jaber’s poem, it explores the emotional weight of Arabic as an inherited language, showing how linguistic memory shapes identity across generations.

🟢 • “Refusing Eurydice” by Ladan Osman

Similarity: Osman, like Jaber, uses fragmented syntax and intimate familial imagery to show how immigrant identities fracture across English and ancestral languages.

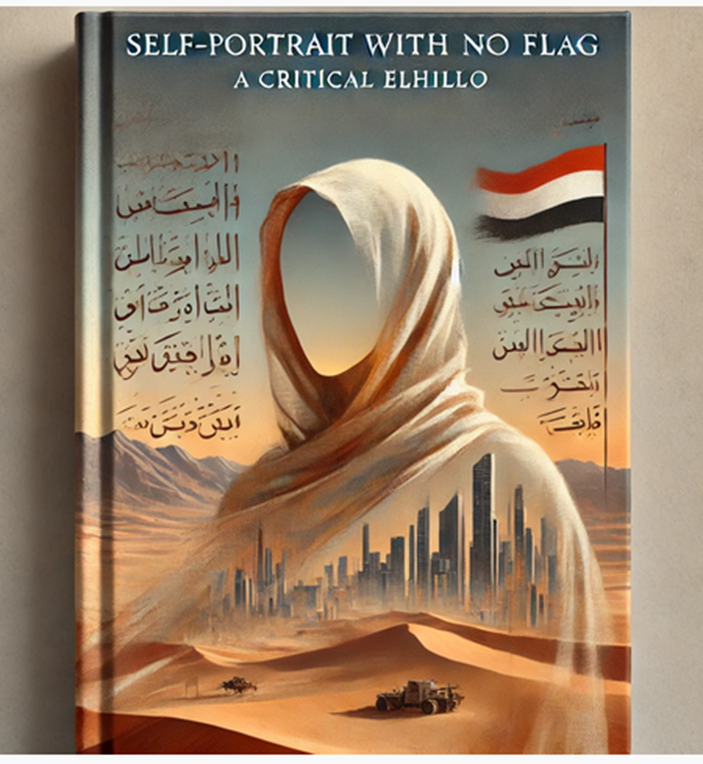

🟠 • “Self-Portrait with No Flag” by Safia Elhillo

Similarity: Elhillo’s poem, like Jaber’s, investigates diasporic identity through hybrid language forms, bodily metaphors, and the tension between inherited culture and adopted English.

Representative Quotations of “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| 🌕 “the language the english no it understand tongue of you” | The speaker mourns the inability of English to carry the emotional and cultural weight of the grandmother’s Arabic. | Postcolonial Theory: Highlights resistance to linguistic hierarchy created by colonial/Western norms; English becomes inadequate for ancestral intimacy. |

| 🔵 “i try and i fail to fit languages of us in each other” | This moment captures the speaker’s emotional frustration at the impossibility of merging linguistic worlds. | Diaspora Studies: Reflects hybrid identity, cultural displacement, and the fractured continuity between generations. |

| 🟣 “i feed you these the morsels… language of me the arabic half-chewed” | The speaker attempts to communicate love through imperfect, broken Arabic shaped by diaspora. | Linguistic Anthropology: Shows language as embodied heritage, transmitted incompletely in diasporic environments. |

| 🟢 “oh teita” | A direct and intimate address to the grandmother, blending tenderness and cultural memory. | Feminist/Matrilineal Theory: Centers women as carriers of cultural knowledge, memory, and emotional lineage. |

| 🔴 “seen i face of you split open by riot laughter” | The grandmother’s laughter becomes a symbol of vitality and cultural rootedness. | Affect Theory: Emotions shape cultural memory and intergenerational identity formation. |

| 🟡 “flecks olive they try to jump from folds of the corners of the eyes of you” | Olive imagery invokes heritage, homeland, and Mediterranean lineage. | Cultural Symbolism Theory: Olive becomes a symbol of origin, memory, and rootedness in diaspora. |

| 🟤 “i split open face of me with spoon, tool blunt & wrong” | The speaker engages in violent introspection to access inherited memory. | Psychoanalytic Theory: Reveals desire to excavate identity and merge self with ancestral lineage. |

| 🟠 “i want from you for you to bleed from in me” | The speaker yearns for the grandmother’s identity to flow into their own self. | Identity Formation Theory: Explores longing for internalized ancestry and psychological merging. |

| 🟣 “i cough out them, always in the time the wrong” | The speaker struggles to articulate questions of heritage at the right moment. | Memory Studies: Shows the fragility and mistiming of diasporic recollection processes. |

| ⚫ “soil of the grave falls it without grace from lips of me” | The ending fuses death, inheritance, and the sedimentation of ancestral memory. | Thanatology & Legacy Theory: Death becomes a medium through which identity and cultural memory are transmitted. |

Suggested Readings: “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English” by Noor Jaber

Books

- Dickins, James, Sándor Hervey, and Ian Higgins. English Poetry and Modern Arabic Verse: Translation and Modernity. Bloomsbury, 2021.

- Marchi, Lisa. The Funambulists: Women Poets of the Arab Diaspora. Syracuse University Press, 2022. Cambridge University Press review, 2025.

Academic Articles

- Fakhreddine, Huda J. “Arabic Poetry in the Twenty-First Century: Translation and Multilingualism.” Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 52, no. 2, 2021, pp. 147-169. https://doi.org/10.1163/1570064X-12341423

- “Functions of Code-Switching in Diasporic Arab Texts.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies (TPLS), vol. 13, no. 1, 2023, pp. ___ [insert pages]. https://tpls.academypublication.com/index.php/tpls/article/download/6767/5485/19745

Poem Websites

- Jaber, Noor (‘Ditee). “Tries the Grammar of the Arabic to Fit the Language the English.” Poets.org, The Academy of American Poets, 2017. https://poets.org/poem/tries-grammar-arabic-fit-language-english

- Jaber, Noor (‘Ditee). “questions arabic asked in english (colonial fit).” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/161048/questions-arabic-asked-in-english-colonial-fit