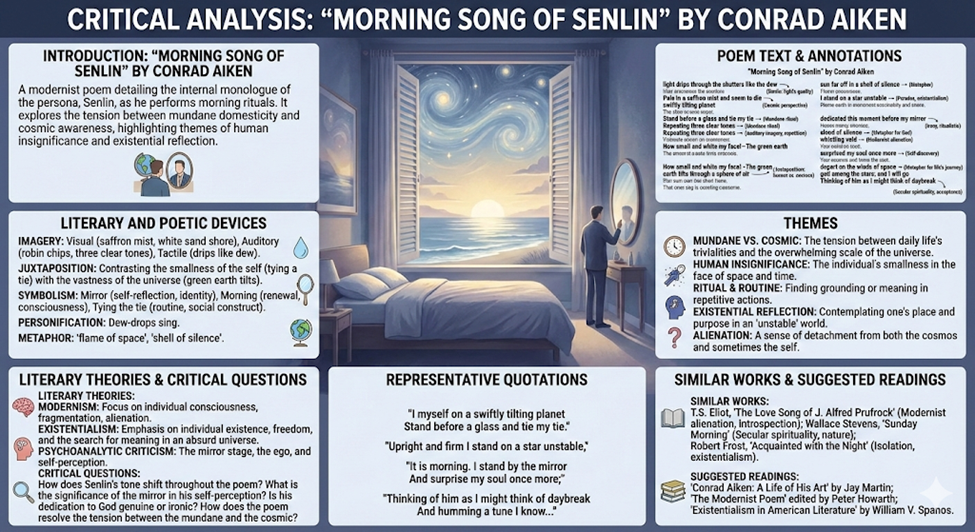

Introduction: “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken first appeared in 1916 and was published in his poetry collection Turns and Movies, marking an early and influential moment in Anglo-American Modernism. The poem presents Senlin as a reflective modern individual caught between cosmic awareness and mundane routine, a tension articulated through recurring acts such as “I stand before a glass and tie my tie,” which juxtapose the trivialities of daily life with vast metaphysical reflection. Aiken blends domestic imagery—“Vine leaves tap my window,” “Dew-drops sing to the garden stones”—with a destabilizing cosmic vision—“Upright and firm I stand on a star unstable”—to dramatize modern man’s search for meaning in a scientifically disenchanted universe. The poem’s popularity lies in this accessible yet philosophically rich structure: it renders existential anxiety and spiritual yearning through familiar rituals, culminating in Senlin’s quiet, tentative faith—“Should I not pause in the light to remember God?”—that neither resolves doubt nor abandons wonder. Its musical repetitions, free-verse cadence, and symbolic fusion of the personal and the planetary have ensured its enduring appeal as a quintessential Modernist meditation on identity, consciousness, and the fragile dignity of ordinary life.

Text: “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

It is morning, Senlin says, and in the morning

When the light drips through the shutters like the dew,

I arise, I face the sunrise,

And do the things my fathers learned to do.

Stars in the purple dusk above the rooftops

Pale in a saffron mist and seem to die,

And I myself on a swiftly tilting planet

Stand before a glass and tie my tie.

Vine leaves tap my window,

Dew-drops sing to the garden stones,

The robin chips in the chinaberry tree

Repeating three clear tones.

It is morning. I stand by the mirror

And tie my tie once more.

While waves far off in a pale rose twilight

Crash on a white sand shore.

I stand by a mirror and comb my hair:

How small and white my face!—

The green earth tilts through a sphere of air

And bathes in a flame of space.

There are houses hanging above the stars

And stars hung under a sea. . .

And a sun far off in a shell of silence

Dapples my walls for me. . .

It is morning, Senlin says, and in the morning

Should I not pause in the light to remember God?

Upright and firm I stand on a star unstable,

He is immense and lonely as a cloud.

I will dedicate this moment before my mirror

To him alone, and for him I will comb my hair.

Accept these humble offerings, cloud of silence!

I will think of you as I descend the stair.

Vine leaves tap my window,

The snail-track shines on the stones,

Dew-drops flash from the chinaberry tree

Repeating two clear tones.

It is morning, I awake from a bed of silence,

Shining I rise from the starless waters of sleep.

The walls are about me still as in the evening,

I am the same, and the same name still I keep.

The earth revolves with me, yet makes no motion,

The stars pale silently in a coral sky.

In a whistling void I stand before my mirror,

Unconcerned, I tie my tie.

There are horses neighing on far-off hills

Tossing their long white manes,

And mountains flash in the rose-white dusk,

Their shoulders black with rains. . .

It is morning. I stand by the mirror

And surprise my soul once more;

The blue air rushes above my ceiling,

There are suns beneath my floor. . .

. . . It is morning, Senlin says, I ascend from darkness

And depart on the winds of space for I know not where,

My watch is wound, a key is in my pocket,

And the sky is darkened as I descend the stair.

There are shadows across the windows, clouds in heaven,

And a god among the stars; and I will go

Thinking of him as I might think of daybreak

And humming a tune I know. . .

Vine-leaves tap at the window,

Dew-drops sing to the garden stones,

The robin chirps in the chinaberry tree

Repeating three clear tones.

Annotations: “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

| Stanza | Text (stanza) | Annotation (what it’s doing) | Literary devices |

| 1 | It is morning, Senlin says, and in the morningWhen the light drips through the shutters like the dew,I arise, I face the sunrise,And do the things my fathers learned to do. | Establishes ritual: morning as repeated, inherited performance. The speaker frames ordinary habits as ancestral continuity. | ⬛ Repetition / refrain (“morning”)🟦 Simile (“like the dew”)🟩 Personification (“light drips”)🟥 Imagery (light, shutters, sunrise)🟪 Symbolism (morning = renewal/tradition) |

| 2 | Stars in the purple dusk above the rooftopsPale in a saffron mist and seem to die,And I myself on a swiftly tilting planetStand before a glass and tie my tie. | Cosmic scale is set against a trivial action (tying a tie). The contrast makes the routine feel both absurd and strangely solemn. | 🟥 Imagery (purple dusk, saffron mist)🟩 Personification (“stars… seem to die”)🔀 Juxtaposition (cosmos vs tie)🟪 Symbolism (tie/mirror = social self, routine)⚖️ Paradox (vast motion vs still stance) |

| 3 | Vine leaves tap my window,Dew-drops sing to the garden stones,The robin chips in the chinaberry treeRepeating three clear tones. | Nature becomes a small orchestra—morning rendered as sound. Repetition (“tones”) introduces a musical motif that will return like a chorus. | 🟩 Personification (leaves tap, dew-drops sing)🟥 Imagery (garden, tree)🔊 Sound effects (tap/sing/chips; tonal motif)⬛ Repetition / refrain (tones as recurring pattern) |

| 4 | It is morning. I stand by the mirrorAnd tie my tie once more.While waves far off in a pale rose twilightCrash on a white sand shore. | Re-anchors the refrain and repeats the tie-ritual. The distant ocean intensifies the contrast: the world is immense, yet the self stays fixed in routine. | ⬛ Repetition / refrain (“It is morning… tie my tie”)🔀 Juxtaposition (mirror room vs ocean)🟥 Imagery (pale rose twilight, white sand shore)🔊 Sound effects (“Crash”) |

| 5 | I stand by a mirror and comb my hair:How small and white my face!—The green earth tilts through a sphere of airAnd bathes in a flame of space. | The mirror triggers self-miniaturization (“How small…”) against planetary motion. The stanza turns grooming into an existential measuring-stick. | 🟥 Imagery (green earth, flame of space)🟩 Personification (“earth… bathes”)🟧 Metaphor (“flame of space”)🔀 Juxtaposition (face vs cosmos)🟪 Symbolism (mirror = self-awareness) |

| 6 | There are houses hanging above the starsAnd stars hung under a sea. . .And a sun far off in a shell of silenceDapples my walls for me. . . | Reality is inverted into dream-logic, suggesting a universe of disorienting layers. The “sun… shell of silence” frames cosmic light as remote and hushed. | ⚖️ Paradox / inversion (houses above stars; stars under sea)🟥 Imagery (sea, sun, dappling)🟧 Metaphor (“shell of silence”)🟩 Personification (“sun… dapples”)🟪 Symbolism (reordered cosmos = destabilized perception) |

| 7 | It is morning, Senlin says, and in the morningShould I not pause in the light to remember God?Upright and firm I stand on a star unstable,He is immense and lonely as a cloud. | The poem pivots from routine to devotion. The speaker’s stability is questioned (“star unstable”), and God is imagined as vast solitude. | ⬛ Repetition / refrain (“It is morning”)❓ Rhetorical question (pause to remember God)⚖️ Paradox (“firm… star unstable”)🟦 Simile (“lonely as a cloud”)🟥 Imagery (light, cloud)🟪 Symbolism (light = spiritual attention) |

| 8 | I will dedicate this moment before my mirrorTo him alone, and for him I will comb my hair.Accept these humble offerings, cloud of silence!I will think of you as I descend the stair. | Prayer is fused with grooming: devotion expressed through the smallest acts. Direct address (“Accept…”) makes the divine intimate, yet still “silent.” | 🟪 Symbolism (mirror/grooming = offering)📣 Apostrophe (direct address to “cloud of silence”)🟧 Metaphor (God as “cloud of silence”)⬛ Repetition (mirror/grooming motif)🟥 Imagery (descending the stair = movement into day) |

| 9 | Vine leaves tap my window,The snail-track shines on the stones,Dew-drops flash from the chinaberry treeRepeating two clear tones. | The natural “chorus” returns with a variation (“two” tones), implying pattern-with-change—morning repeats, but never identically. | ⬛ Refrain (return of vine/dew motif)🟩 Personification (leaves tap)🟥 Imagery (snail-track shines; dew-drops flash)🔊 Sound/musical motif (“tones”) |

| 10 | It is morning, I awake from a bed of silence,Shining I rise from the starless waters of sleep.The walls are about me still as in the evening,I am the same, and the same name still I keep. | Awakening is described through layered metaphors (bed/waters), but identity feels unchanged (“same… same name”). Morning becomes a test of self-continuity. | ⬛ Repetition (“same… same”)🟧 Metaphor (“bed of silence”; “waters of sleep”)🟥 Imagery (starless, walls)🟦 Simile (“still as in the evening”)🟪 Symbolism (name = identity) |

| 11 | The earth revolves with me, yet makes no motion,The stars pale silently in a coral sky.In a whistling void I stand before my mirror,Unconcerned, I tie my tie. | Huge motion is rendered as felt stillness, while the speaker performs routine “unconcerned.” The tie becomes a symbol of composure amid cosmic emptiness. | ⚖️ Paradox (revolves yet “no motion”)🟥 Imagery (coral sky, void, mirror)🔊 Sound effects (“whistling void”)🔀 Juxtaposition (void vs tie)🟪 Symbolism (tie = social armor/normalcy) |

| 12 | There are horses neighing on far-off hillsTossing their long white manes,And mountains flash in the rose-white dusk,Their shoulders black with rains. . . | A sweeping landscape montage: movement, sound, and color. Personified mountains (“shoulders”) turn nature into a living presence. | 🟥 Imagery (rose-white dusk, black rains, white manes)🟩 Personification (mountains’ “shoulders”)🔊 Sound effects (neighing)🟪 Symbolism (wildness beyond the room) |

| 13 | It is morning. I stand by the mirrorAnd surprise my soul once more;The blue air rushes above my ceiling,There are suns beneath my floor. . . | The “mirror moment” becomes spiritual shock: the self is startled by its own existence. The stanza intensifies surreal verticality (suns below). | ⬛ Repetition / refrain (mirror stance)🟧 Metaphor (“surprise my soul”)🟩 Personification (“air rushes”)⚖️ Paradox (suns beneath floor)🟥 Imagery (blue air, suns) |

| 14 | . . . It is morning, Senlin says, I ascend from darknessAnd depart on the winds of space for I know not where,My watch is wound, a key is in my pocket,And the sky is darkened as I descend the stair. | Departure is both literal (stairs) and metaphysical (winds of space). The watch/key are compact symbols of time and agency, while darkness persists into “morning.” | ⬛ Refrain (“It is morning, Senlin says”)🟧 Metaphor (life-journey as space-departure)🟪 Symbolism (watch = time; key = access/choice)⚖️ Paradox (ascend from darkness / descend stair; dark sky in morning)🟥 Imagery (winds, darkened sky) |

| 15 | There are shadows across the windows, clouds in heaven,And a god among the stars; and I will goThinking of him as I might think of daybreakAnd humming a tune I know. . . | The divine is normalized—thought of like “daybreak,” not as spectacle but as habit. The “tune” links faith to the poem’s ongoing musical refrain. | 🟥 Imagery (shadows, clouds, stars)🟦 Simile (“as… daybreak”)🟪 Symbolism (daybreak = faith as daily certainty)🔊 Sound motif (humming/tune)🔀 Juxtaposition (god among stars vs ordinary going) |

| 16 | Vine-leaves tap at the window,Dew-drops sing to the garden stones,The robin chirps in the chinaberry treeRepeating three clear tones. | The poem closes by returning to the natural chorus, completing the circular structure. The repeated “three clear tones” seals morning as patterned music. | ⬛ Refrain (full return of opening nature motif)🟩 Personification (tap, sing)🔊 Sound effects (chirps; “three clear tones”)🟥 Imagery (window, stones, tree) |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

| Device | Example from the Poem | Explanation |

| 1 ◆ Alliteration | “Stars in the purple dusk” | Repetition of initial consonant sounds enhances musical flow and sonic cohesion. |

| 2 ● Anaphora | “It is morning, Senlin says…” | Repeated opening phrase emphasizes routine, cyclic time, and consciousness. |

| 3 ▲ Assonance | “dew-drops sing to the garden stones” | Repetition of vowel sounds produces internal rhyme and lyric softness. |

| 4 ✦ Cosmic Imagery | “Upright and firm I stand on a star unstable” | Places human existence within a vast, unstable universe, a Modernist concern. |

| 5 ◇ Contrast | “tie my tie” vs. “winds of space” | Juxtaposes mundane routine with cosmic infinity to stress existential tension. |

| 6 ▣ Free Verse | Entire poem | Absence of fixed meter or rhyme mirrors fragmented modern consciousness. |

| 7 ☀ Imagery (Visual) | “Stars pale silently in a coral sky” | Creates vivid sensory pictures that ground abstract thought in perception. |

| 8 ⊗ Irony | “Unconcerned, I tie my tie” | Calm routine persists despite awareness of cosmic instability and insignificance. |

| 9 ★ Metaphor | “a star unstable” | Metaphor for the precarious foundation of human existence. |

| 10 ◐ Modernist Alienation | “How small and white my face!” | Expresses self-estrangement and diminished identity. |

| 11 ☼ Motif (Morning) | Repeated references to “morning” | Symbolizes awakening, consciousness, and repeated renewal. |

| 12 ♫ Musicality | “Repeating three clear tones” | Sound imagery reinforces rhythm and lyric movement. |

| 13 ⟁ Paradox | “The earth revolves with me, yet makes no motion” | Highlights contradiction between perception and reality. |

| 14 ❖ Personification | “Vine leaves tap my window” | Grants nature human actions, softening the poem’s cosmic scale. |

| 15 ⟳ Repetition | “I stand by the mirror” | Reinforces ritual, self-scrutiny, and monotony of modern life. |

| 16 ✝ Religious Allusion | “Should I not pause…to remember God?” | Introduces spiritual reflection without doctrinal certainty. |

| 17 ◍ Symbolism (Mirror) | “I stand before my mirror” | Represents self-awareness, identity, and introspection. |

| 18 ⧗ Symbolism (Tie) | “tie my tie” | Symbol of social conformity and mechanical routine. |

| 19 ⇅ Tone Shift | Wonder → detachment | Movement between awe and indifference reflects inner conflict. |

| 20 ✧ Transcendental Imagery | “There are suns beneath my floor” | Suggests hidden metaphysical realities beneath ordinary life. |

Themes: “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

✦ Existential Consciousness and the Modern Self

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken explores the emergence of modern existential consciousness through Senlin’s heightened awareness of his own smallness within an immense and unstable universe. The poem repeatedly situates the speaker before a mirror, a symbolic space where private identity confronts cosmic reality, and while Senlin continues to perform habitual acts such as tying his tie, he simultaneously recognizes that he stands “upright and firm” on a “star unstable.” This disjunction between awareness and action reflects the Modernist condition in which intellectual perception expands while agency remains limited. Senlin’s consciousness ranges across planetary motion, astronomical distance, and metaphysical silence, yet his life proceeds unchanged, suggesting a form of existential paralysis. Aiken thus portrays the modern self as deeply reflective but internally divided, capable of insight without transformation. The theme ultimately emphasizes that modern awareness, rather than liberating the individual, often intensifies uncertainty and heightens the burden of self-conscious existence.

☼ The Ritual of Routine versus Cosmic Vastness

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken powerfully juxtaposes ordinary human routine with the overwhelming vastness of the cosmos in order to reveal the irony and fragility of modern life. Everyday actions—combing hair, winding a watch, descending the stair—are enacted against images of revolving planets, fading stars, and the vast “winds of space,” thereby placing the insignificant details of human existence within an infinite and indifferent universe. This contrast does not diminish routine entirely; instead, it reveals routine as a stabilizing mechanism that enables psychological survival amid cosmic disorientation. Repetition in the poem reinforces the persistence of habit, while cosmic imagery continually undermines any sense of absolute meaning or control. Aiken suggests that modern individuals cling to routine not out of blindness but out of necessity, using familiar gestures as a quiet resistance to existential anxiety and metaphysical uncertainty.

✝ Spiritual Uncertainty and Tentative Faith

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken articulates a distinctly Modernist vision of spirituality marked by uncertainty, introspection, and provisional belief rather than doctrinal assurance. Senlin’s reflective question—whether he should pause “to remember God”—signals a faith that emerges from contemplation rather than religious obligation. God is imagined as “immense and lonely as a cloud,” a metaphor that conveys distance, silence, and abstraction, aligning divinity with cosmic immensity rather than personal intimacy. Senlin’s act of devotion is modest and symbolic, consisting of dedicating a private moment before the mirror rather than performing a public ritual. This restrained gesture reflects a modern spiritual sensibility shaped by scientific awareness and intellectual doubt. Aiken thus presents faith as an inward, reflective act that survives not through certainty but through humility, questioning, and the persistence of spiritual longing in an uncertain universe.

◍ Identity, Self-Reflection, and Alienation

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken offers a profound exploration of modern alienation through the recurring motif of self-examination and the speaker’s fractured sense of identity. The mirror becomes a site of confrontation where Senlin observes his own physical smallness and emotional detachment, describing his face as “small and white,” a phrase that underscores vulnerability and estrangement. Despite his expansive cosmic awareness, Senlin remains socially and psychologically unchanged, retaining the same name, habits, and outward identity. This gap between inward realization and outward continuity intensifies the sense of alienation, suggesting that self-awareness does not necessarily produce self-integration. Aiken captures the Modernist condition in which individuals possess acute intellectual insight yet remain isolated within themselves, suspended between knowledge and action, reflection and routine.

Literary Theories and “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

| Literary Theory | Core Critical Focus | References from the Poem | Interpretation through the Theory |

| Modernist / Existentialist Criticism 🧠 | Alienation, routine, fragmented self, insignificance of the individual in a mechanized or indifferent universe | “I myself on a swiftly tilting planet / Stand before a glass and tie my tie”“Unconcerned, I tie my tie”“The earth revolves with me, yet makes no motion” | 🧠 The speaker embodies the modern individual trapped in ritual—tying a tie while standing on a “swiftly tilting planet.” 🧠 The contrast between cosmic motion and emotional detachment highlights existential absurdity. 🧠 The repeated morning routine reflects meaning sought but never fully achieved, a hallmark of Modernist anxiety. |

| Cosmological / Metaphysical Criticism 🌌 | Relationship between human consciousness and the vast universe; tension between microcosm and macrocosm | “The green earth tilts through a sphere of air”“There are houses hanging above the stars”“I ascend from darkness / And depart on the winds of space” | 🌌 The poem persistently places the self inside a moving cosmos, collapsing boundaries between room, planet, and universe. 🌌 Everyday actions (combing hair, descending stairs) occur within metaphysical infinity, suggesting that human life is both negligible and mysteriously connected to cosmic order. |

| Psychoanalytic Criticism 🪞 | Identity formation, self-recognition, ego-consciousness, repetition compulsion | “I stand by the mirror” (repeated)“How small and white my face!”“I surprise my soul once more” | 🪞 The mirror functions as a site of ego-confrontation, where the self repeatedly seeks coherence. 🪞 The speaker’s surprise at his own soul implies unstable identity, constantly renegotiated each morning. 🪞 Repetition of grooming rituals suggests a compulsion to stabilize the psyche against cosmic disorientation. |

| Religious / Spiritual Criticism ✝️ | Human relationship with God, ritualized faith, sacredness within ordinary life | “Should I not pause in the light to remember God?”“He is immense and lonely as a cloud”“Accept these humble offerings, cloud of silence!” | ✝️ God is imagined not as doctrine but as presence and silence, integrated into daily acts. ✝️ Grooming becomes a devotional ritual, replacing formal prayer. ✝️ Faith is modernized—God is remembered as naturally as “daybreak,” reflecting quiet, non-dogmatic spirituality rather than institutional religion. |

Critical Questions about “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

✦ How does the poem reconcile ordinary routine with cosmic awareness?

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken interrogates the uneasy coexistence of habitual human routine and an expanded awareness of cosmic vastness, presenting them not as reconciled but as perpetually co-present. Senlin performs ordinary acts—tying his tie, combing his hair, winding his watch—while simultaneously recognizing that he stands on a “star unstable,” suspended within a vast, indifferent universe. Rather than allowing cosmic insight to disrupt routine, the poem insists on their parallel persistence, suggesting that modern consciousness is capable of holding contradiction without resolution. The routine does not negate cosmic awareness, nor does awareness dismantle routine; instead, each sharpens the other’s significance. Aiken implies that modern life is structured by this tension, where individuals intellectually grasp their insignificance yet continue to act as social beings bound by time, habit, and order. The poem thus reframes routine as a coping mechanism rather than a failure of imagination.

☼ What role does the mirror play in shaping Senlin’s self-awareness?

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken employs the mirror as a central symbolic device through which self-awareness, identity, and alienation are repeatedly staged. Each return to the mirror becomes a moment of confrontation between the inner, reflective consciousness and the outward, socially constituted self, revealing a subject who is acutely aware yet fundamentally unchanged. Senlin’s observation of his “small and white” face underscores a diminished sense of personal significance, especially when juxtaposed with the immense cosmic imagery that surrounds him. The mirror does not offer self-knowledge in a redemptive sense; instead, it confirms the limits of introspection, showing that awareness alone does not generate transformation. By situating metaphysical reflection within this intimate, domestic space, Aiken suggests that modern identity is shaped less by heroic action than by repetitive self-scrutiny. The mirror thus becomes a site of existential recognition rather than self-mastery.

✝ How does the poem represent faith in a modern, scientific universe?

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken presents faith as tentative, introspective, and deeply shaped by modern scientific consciousness rather than by traditional religious certainty. Senlin’s question—whether he should pause to remember God—signals a reflective rather than obedient spirituality, one that arises from contemplation amid cosmic awareness. God is imagined as “immense and lonely as a cloud,” a metaphor that aligns divinity with vastness and silence instead of intimacy or authority. This portrayal reflects a universe governed by astronomical forces rather than divine intervention, where belief survives not as dogma but as inward gesture. Senlin’s humble dedication of a private moment before the mirror suggests that faith, in the modern condition, becomes symbolic, personal, and provisional. Aiken neither affirms nor denies God’s presence; instead, he dramatizes the struggle to sustain spiritual meaning in a world increasingly explained by science and abstraction.

◍ Why does Senlin remain unchanged despite profound awareness?

“Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken deliberately resists narrative or psychological transformation, portraying Senlin as a figure who gains awareness without achieving change, thereby embodying a key Modernist insight. Despite his repeated recognition of cosmic instability, metaphysical vastness, and spiritual uncertainty, Senlin ends where he begins—performing the same actions, keeping the same name, and descending the same stair. This stasis is not presented as moral failure but as a realistic condition of modern existence, in which insight does not automatically confer agency or purpose. Aiken suggests that modern individuals are often trapped between knowledge and action, capable of perceiving the complexity of existence yet constrained by social structures and internal inertia. Senlin’s unchanged state underscores the poem’s critical argument: awareness deepens consciousness but does not guarantee meaning, resolution, or transcendence, leaving the modern subject suspended in reflective continuity.

Literary Works Similar to “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

- 🌅 “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T. S. Eliot

Similarity: Like Senlin, Prufrock is a Modernist speaker trapped in repetitive routines, intensely self-aware, measuring existence through trivial actions while confronting the vast, unsettling implications of time, identity, and meaning. - 🪞 “Aubade” by Philip Larkin

Similarity: Both poems use morning as a moment of existential reckoning, where awakening does not bring hope but instead sharpens consciousness of mortality, isolation, and the uneasy persistence of the self. - 🌌 “Snow” by Wallace Stevens

Similarity: Stevens’s poem, like Aiken’s, explores perception and consciousness against a stark, impersonal universe, emphasizing how the mind struggles to locate meaning within an indifferent cosmic order. - ✨ “Ode to a Nightingale” by John Keats

Similarity: Although Romantic in origin, the poem resembles Senlin in its oscillation between mundane human awareness and transcendental experience, contrasting bodily limitation with imaginative or cosmic escape.

Representative Quotations of “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

| Quotation | Context & Theoretical Perspective | Explanation |

| ✦ “Upright and firm I stand on a star unstable” | Existentialism / Modernist Cosmology | The line encapsulates the paradox of human confidence amid cosmic instability, reflecting Modernist anxiety produced by scientific understandings of the universe. |

| ☼ “It is morning, Senlin says” | Temporal Cyclicality / Modernist Routine | The recurring declaration emphasizes cyclical time and habitual consciousness, central to Modernist representations of mechanized daily life. |

| ◍ “I stand before a glass and tie my tie” | Identity Formation / Modernist Alienation | The mirror and tie symbolize social identity and conformity, suggesting that selfhood is maintained through routine rather than authentic transformation. |

| ❖ “Vine leaves tap my window” | Personification / Nature vs. Self | Human traits assigned to nature soften the cosmic vastness and create a fragile intimacy between the self and the external world. |

| ⟁ “The earth revolves with me, yet makes no motion” | Paradox / Phenomenology | This contradiction highlights the gap between scientific reality and human perception, a key Modernist philosophical concern. |

| ✝ “Should I not pause in the light to remember God?” | Spiritual Crisis / Modernist Faith | The question reflects tentative belief shaped by doubt, presenting faith as reflective rather than doctrinal. |

| ★ “He is immense and lonely as a cloud” | Metaphysical Metaphor / De-personalized Divinity | God is rendered abstract and distant, aligning spirituality with cosmic loneliness rather than intimacy. |

| ⊗ “Unconcerned, I tie my tie” | Irony / Existential Detachment | The calm tone contrasts sharply with cosmic awareness, underscoring emotional detachment in modern life. |

| ♫ “Repeating three clear tones” | Musical Structure / Lyric Modernism | Sound repetition reinforces cyclical rhythm and creates a counterpoint to philosophical abstraction. |

| ⇅ “I am the same, and the same name still I keep” | Stasis / Modernist Anti-Bildungsroman | Despite heightened awareness, the speaker remains unchanged, rejecting traditional narratives of growth or resolution. |

Suggested Readings: “Morning Song of Senlin” by Conrad Aiken

- Books

- Aiken, Conrad. Selected Poems. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Aiken, Conrad. The Charnel Rose, Senlin: A Biography, and Other Poems. The Four Seas Company, 1918.

- Academic

- Brown, Calvin S. “The Achievement of Conrad Aiken.” The Georgia Review, vol. 27, no. 4, 1973, pp. 477–488. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41397003. Accessed 20 Jan. 2026.

- Fleissner, Robert F. “Reverberations of Prufrock’s Evening Performance in Aiken’s ‘Morning Song of Senlin’.” CLA Journal, vol. 36, no. 1, 1992, pp. 31–40. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44329512. Accessed 20 Jan. 2026.

- Poem

- Aiken, Conrad. “Morning Song of Senlin.” InfoPlease (Primary Sources: Poetry—Modern Verse), 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.infoplease.com/primary-sources/poetry/modern-verse/conrad-aiken-morning-song-senlin. Accessed 20 Jan. 2026.

- Rittenhouse, Jessie Belle, editor. The Project Gutenberg eBook of Modern American Poetry. Project Gutenberg, eBook no. 58992, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/58992/pg58992-images.html. Accessed 20 Jan. 2026.