Introduction: “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

“A Small, Good Thing,” written by Raymond Carver, first appeared in The New Yorker in 1983. Later included in his critically acclaimed 1984 collection Cathedral, the short story became one of his most beloved works and a literary classic. With its poignant and understated exploration of grief and unexpected human connection, “A Small, Good Thing” continues to resonate with readers today.

Main Events in “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

- Birthday Tragedy: On his eighth birthday, Scotty is hit by a car while walking to school. He initially seems alright but soon collapses into unconsciousness.

- Hospitalization: Scotty is rushed to the hospital where he slips into a coma. Doctors offer reassurance, but the prognosis remains uncertain.

- Parental Vigil: Ann and Howard keep a relentless vigil by Scotty’s bedside, clinging to hope while their anxiety and despair grow.

- Mysterious Calls: A local baker repeatedly calls about a birthday cake Ann ordered, unaware of the tragedy. The calls become a source of irritation and increasing distress.

- Mounting Tension: The baker’s insistence and the parents’ emotional turmoil build unbearable tension. The cake becomes a symbol of their shattered normalcy.

- Frustration Peaks: Driven by mounting anger and grief, Ann and Howard decide to confront the baker late at night.

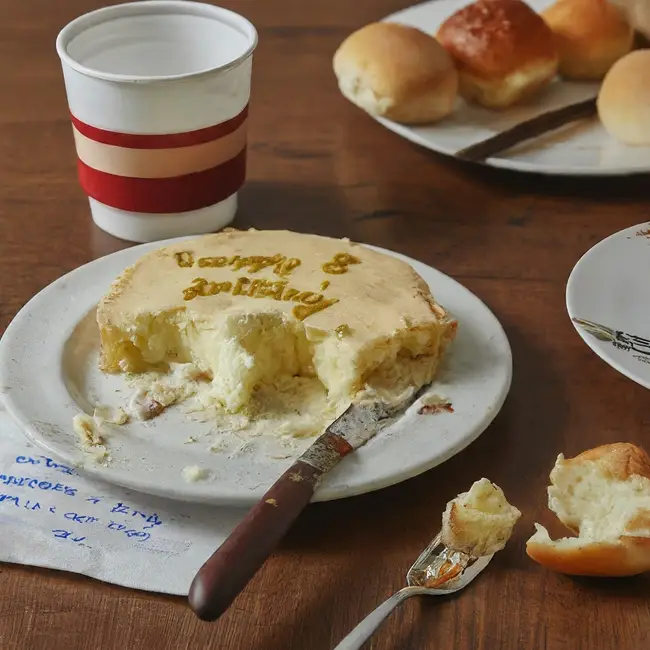

- Unexpected Encounter: The baker, a solitary and somewhat gruff man, welcomes them unexpectedly with warmth. He offers coffee and freshly baked rolls.

- Shared Humanity: As they sit in the baker’s simple kitchen, he shares stories of his own life and losses. This unexpected connection offers a brief respite from their overwhelming pain.

- Moment of Solace: In this shared act of eating and storytelling, a small sense of peace and understanding descends upon the parents.

- Ambiguous Ending: The story typically ends without explicitly revealing Scotty’s fate. The focus remains on the fragile power of human connection amidst profound suffering and the lingering question of hope.

Literary Devices in “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

1. Symbolism

- The Cake: Represents the hope, normalcy, and celebration Ann and Howard cling to, which starkly contrasts the tragedy they face.

- “…the boy’s birthday cake … with the inscription ‘Happy 8th Birthday Scotty!'”

- The Rolls: Become a symbol of shared humanity, comfort, and connection with the baker near the end.

- “They ate rolls and drank coffee… The baker was encouraged. He began to recall other incidents in his life…”

2. Irony

- Situational Irony: The stark contrast between the joyful task of ordering a birthday cake and then receiving news of Scotty’s accident is a powerful use of situational irony.

- “Ann Weiss was at the bakery… ‘Happy 8th Birthday Scotty!’ … ‘Scotty, honey, how are you?’…’His head was covered with bandages…'”

- Dramatic Irony: The reader is aware of Scotty’s increasingly dire condition, a fact unknown to his parents for much of the story, creating a sense of tension and tragedy.

- The Baker’s Calls: The baker’s increasingly ominous telephone calls foreshadow the negative turn of events.

- “[The baker says] ‘If you could pick it up by five, that would be a big help…I mean, something else has come up… I know you won’t mind, but I’m going to have to ask you to pick it up by one o’clock today.'”

4. Minimalism

- Sparse Dialogue and Descriptions: Carver’s signature minimalist style uses simple language with stark detail, leaving room for the reader’s emotional interpretation.

- “It was night in the hospital room…She closed her eyes and tried to think about Scotty.”

- Understated emotion: Characters’ feelings are often implied, not explicitly stated, increasing the emotional impact.

5. Imagery

- Vivid Hospital Scenes: Create a feeling of sterile dread and helplessness.

- “It was night in the hospital room…Nurses moved about softly, and from another room she could hear someone moaning”

6. Metaphor

- Darkness and Sleep: Represent the unknown, fear, and possible death

- “… she tried to think about Scotty. But she was afraid to think about Scotty… She fell asleep… She slept hard.”

7. Simile

- Comparison to an Animal: Likens Ann to a cornered animal, emphasizing her desperation and vulnerability

- “She went back and forth in her mind… like a trapped animal.”

8. Allusion

- Biblical References: Subtly appear when Ann sees a black family praying, potentially alluding to a shared experience of grief and searching for spiritual comfort .

- “They were in the same kind of waiting as she was in… the woman’s lips moved silently.”

- Celebration and Tragedy: The initial birthday scene juxtaposed with the accident heightens the emotional impact .

- Waiting and Uncertainty: The contrast between the characters’ anxious waiting and the doctor’s clinical detachment reveals the gulf between the emotional and the medical.

10. Diction

- Simple, Everyday Language: Creates a sense of realism and immediacy.

- Repetition of Words: Words like “wait”, “phone”, and “Scotty” reinforce the characters’ obsessive focus.

11. Epiphany

- Final Moment of Connection: The sharing of food and stories with the baker represents a small epiphany of shared humanity and solace for the characters and the reader.

12. Ambiguity

- Open Ending: The story does not give a clear resolution about Scotty’s fate, leaving the reader to ponder the themes of hope, despair, and the fleeting nature of solace.

13. Tone Shifts:

- From mundane to tense to resigned, reflecting the emotional rollercoaster.

14. Understatement:

- Minimizes direct expressions of emotion, increasing the story’s power.

15. Motif

- Waiting: The act of waiting for news and resolution drives the narrative.

Characterization in “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

Carver’s “A Small, Good Thing” features subtly complex characterization despite its stylistic minimalism. Let’s explore the key figures:

Ann and Howard Weiss

- Initially Defined by Ordinary Life: When we first meet them, they’re engaged in the mundane: getting a birthday cake, planning a party. This ordinariness makes their tragedy all the more impactful.

- Understated Grief: Carver doesn’t offer long, anguished outpourings of emotion. Grief manifests in small, telling gestures—Ann’s inability to truly think about Scotty, Howard’s nervous energy.

- Transformation Through Shared Experience: The encounter with the baker forces them from private grief into a shared space of vulnerability. This subtly shifts their portrayal from devastated parents to people capable of finding brief solace in connection.

The Baker

- Starts as Antagonistic: His insistent phone calls make him initially unsympathetic, almost a representation of the relentless cruelty of fate.

- Reveals Hidden Humanity: As he stays open in the night, sharing coffee and rolls, he becomes a surprising symbol of human compassion. He’s not untouched by tragedy himself but finds a way to extend a lifeline, however small, in the darkness.

- Archetypal Figure: In some ways, he reads like an archetype – the solitary wise man offering food as a symbol of comfort and connection.

Scotty

- Defined by Absence: Scotty is mostly a silent presence. We see the cake, his empty bed. This absence makes him both heartbreaking and universal. He embodies any child facing the unthinkable.

Minor Characters

- Dr. Francis: Represents the impersonal aspect of medicine, his clinical detachment contrasting with the parents’ emotions. This allows for a critique of how medical systems sometimes fail the emotional needs of patients and families.

- Franklin’s Family: Their brief appearance emphasizes the universality of pain and the human need for connection during hardship.

What Makes Carver’s Characterization Unique

- Focus on the Unspoken: The characters’ inner lives are implied, requiring the reader to actively engage their own emotions in the story.

- Transformation, not Resolution: The story doesn’t aim to resolve trauma, but to capture the moment when characters are forced to evolve in order to cope.

- Symbolism of Everyday Objects: The cake, the rolls – mundane objects carry enormous emotional weight, illustrating how small acts and shared experiences hold meaning in even the darkest times.

Major Themes in “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

Here’s a breakdown of the major themes found in Raymond Carver’s “A Small, Good Thing,” along with how they are explored in the story:

1. The Fragility of Joy and the Inevitability of Suffering

- The Birthday Contrast: The story starts with celebratory normalcy: ordering the cake, preparing for a party. The suddenness of Scotty’s accident brutally juxtaposes how easily and unexpectedly tragedy can strike, shattering ordinary happiness.

- The Waiting Room as Purgatory: The hospital becomes a liminal space between hope and despair, underscoring the universally shared experience of suffering and loss.

2. Isolation vs. Connection

- Initial Isolation: Ann and Howard are trapped in their own anxieties, isolated from each other and from the world. Carver highlights this through their stilted conversations and the separate ways they try to cope.

- The Baker as a Connection: The initially abrasive baker becomes the catalyst for human connection. The shared act of eating, talking, and remembering creates a bridge across their separate sorrows.

- Ambiguous Power of Connection: The ending doesn’t suggest resolution, but the fleeting possibility of connection as a means of surviving the darkness.

3. The Limits of Communication and Understanding

- Miscommunication with the Doctor: Dr. Francis’s detached delivery of information and clinical coldness emphasizes the gap between medical language and the emotional experience of the parents. This highlights the inadequacy of words in the face of immense grief.

- Silence as Communication: The most powerful moments are those of shared silence – Ann and Howard at Scotty’s bedside, or sharing rolls with the baker. These emphasize how profound communication can sometimes exist beyond verbal language.

4. The Search for Meaning in the Face of the Absurd

- The Unanswered “Why”: The story doesn’t provide an explanation for Scotty’s accident or potential fate. This reflects the often senseless nature of tragedy, forcing both the characters and the reader to confront the incomprehensible.

- Small Gestures as Meaning-Making: Baking, sharing food, talking about past hardships – these become tiny acts of defiance in the face of the absurd. They offer not answers, but a way to exist in defiance of meaningless suffering.

Writing Style in “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

- Sparse Prose and Dialogue

- Short, Simple Sentences: Carver favors unadorned sentences and minimal modifiers, leaving the impact to rest on carefully chosen nouns and verbs. For example, “His head was covered in bandages. He didn’t move.”

- Understated Dialogue: Conversations are clipped, with emphasis on what characters don’t say. This forces the reader to infer emotions and navigate the fraught subtext in conversations.

- Emotional Impact Through Implication

- Show, Don’t Tell: Carver doesn’t give us long descriptions of emotions. Instead, he reveals inner turmoil through gestures or actions. For example, Ann’s struggle to imagine Scotty, or Howard’s constant nervous movement, reveal their grief far more effectively than if directly stated.

- “The Iceberg Theory”: Like Hemingway, Carver believed stories should focus on surface details, implying a vastness of emotion below the surface. The reader becomes a co-creator, filling in the emotional blanks.

- Focus on the Ordinary

- Working-Class Characters: Carver often writes about ordinary people, like the Weisses and the baker, grappling with everyday concerns. This adds universal relatability to the story.

- The Power of Mundane Detail: The cake, the rolls, the repetitive phone calls – these objects take on heightened significance because of the tragedy surrounding them. This underscores that profound experiences can occur within the seemingly mundane.

- Ambiguity and Open Endings

- Unresolved Fate: The reader never gets definitive clarity about Scotty’s fate. This ambiguity denies neat closure, mimicking the uncertainty of life and making the story linger in the reader’s mind.

- Emphasis on the Moment: Carver cares less about the past or future and more on the intense emotional present of his characters. This allows for subtle shifts and glimmerings of hope, but never simplistic resolution.

- Use of Symbols and Motifs

- Objects with Emotional Weight: The cake and the rolls transform from symbols of joy/annoyance to vessels for grief and finally shared humanity.

- Recurring Motifs: Acts of waiting, phone calls, and sleep/wakefulness create a pattern that builds tension and reflects the characters’ changing emotional states

Literary Theories and Interpretation of “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

- Emphasis on the Reader’s Experience: This theory suggests that the meaning of a text isn’t fixed but actively constructed by the reader. Carver’s minimalism and ambiguity provide plenty of space for the reader’s emotional response.

- Interpretation #1: Focus on Grief: A reader heavily influenced by personal experiences of grief might focus on Ann and Howard’s suffering, the story becoming an exploration of how parents cope with the unthinkable.

- Interpretation #2: Focus on Connection: Another reader might focus on the final scene with the baker, interpreting it as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit in the face of darkness.

- The Text Itself: This theory focuses on close analysis of literary devices within the story itself, aiming for objective interpretation.

- Example: Analyzing the cake’s symbolism, from celebratory object to painful reminder to connection point, without necessarily delving into the author’s intent or the reader’s personal experience.

- Unconscious Motivations: A Freudian reading might examine the characters’ actions as manifestations of repressed desires or anxieties.

- Possible Interpretation: The baker, initially harsh, could be seen as unknowingly projecting his own past grief. The shared meal becomes a subconscious ritual of connection, seeking solace he cannot verbalize.

- Gender Roles and Silence: A feminist lens might examine how Ann is defined by motherhood and domestic roles. Is her silence a reflection of societal expectations of a grieving woman?

- Counterpoint: The baker, who offers the traditionally female act of feeding, could be subverting gendered roles and offering the type of emotionally direct support society typically denies to men.

- Challenging Binary Oppositions: Deconstruction would focus on unsettling seemingly clear contrasts in the story: joy/sorrow, life/death, connection/isolation.

- Questioning the Ending: Does the shared meal truly indicate a shift towards healing, or does it highlight the futility of small gestures in the face of immense tragedy?

Important Note:

- No Single “Right” Interpretation: Different theories offer different lenses, each highlighting unique aspects of the story.

- Carver’s Style Invites This: Carver’s subtle complexities and lack of neat resolution make his work particularly well-suited to analysis through various theoretical frameworks.

Questions and Thesis Statements about “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

1. Question: How does Carver’s minimalist style influence the reader’s emotional experience of the story?

Thesis: Carver’s minimalist style intentionally leaves emotional and narrative gaps, forcing the reader to actively participate in the creation of meaning and experience a heightened intensity of grief, uncertainty, and the longing for connection.

2. Question: To what extent does the open-ended conclusion offer genuine hope, or does it underscore the enduring futility of human connection in the face of tragedy?

Thesis: The ambiguous ending of “A Small, Good Thing” highlights a powerful tension between the fleeting but potent nature of human connection and the overwhelming presence of senseless suffering, leaving the reader to determine the balance between hope and despair.

3. Question: How does the evolving symbolism of the birthday cake illuminate the profound shifts in the characters’ perspectives on life and suffering?

Thesis: The birthday cake transforms from a symbol of joyous anticipation to a painful reminder of loss, and ultimately, a catalyst for a shared experience of grief and humanity, reflecting the characters’ forced journey from the ordinary to the harrowing depths of the human experience.

4. Question: Does the character of the baker function primarily as an antagonist to heighten the parents’ suffering, or does he reveal an unexpected dimension of compassion and vulnerability within himself?

Thesis: The baker’s initial abrasiveness and subsequent softening illustrate the intricate duality of human experience, where those who seem isolated in their own pain can ultimately offer unexpected solace and connection to others.

5. Question: In what ways does the story challenge or support traditional expectations of how grief and trauma should be expressed or processed?

Thesis: “A Small, Good Thing” subverts expectations of overt emotional outpouring by portraying grief as fractured, internalized, and often expressed through seemingly insignificant details and gestures, offering a more realistic and nuanced portrayal of trauma.

Short Question-Answer “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

- Question: Why is the story’s title ironic?

Answer: The title suggests a comforting, positive resolution, which drastically contrasts with Scotty’s accident (“His head was covered in bandages. He didn’t move”) and the unsettling open ending. This irony spotlights how even small acts of kindness cannot erase immense suffering.

- Question: How does silence function as a form of communication in the story?

Answer: The most potent moments of the story involve silence – Ann and Howard at Scotty’s bedside (“They sat quietly…She closed her eyes”), and the shared, quiet meal with the baker (“They ate rolls and drank coffee…”). These emphasize that connection and empathy can transcend language.

- Question: Does the doctor’s clinical detachment serve a purpose in the story?

Answer: Dr. Francis’ coldness (“The doctor was a short man with a clipped mustache…”) highlights the gap between the medical facts of Scotty’s condition and the emotional turmoil of his family. It underscores the dehumanizing aspects of tragedy when reduced to medical terminology.

- Question: Why does the story focus on such ordinary details (the cake, the rolls)?

Answer: By imbuing mundane objects with emotional weight—from the birthday cake with its inscription to the simple rolls—Carver shows that profound meaning and change can exist within seemingly insignificant moments of everyday life.

- Question: Is the ending hopeful or despairing?

Answer: The ambiguity of the ending is intentional. The shared meal suggests a flicker of connection, but Scotty’s potential fate remains unknown. This tension invites a reader’s personal interpretation, reflecting their own outlook on the world and the balance between connection and suffering.

Suggested Readings: “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

Absolutely! Here’s a selection of suggested readings to pair with “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver, formatted in proper MLA style:

Works by Raymond Carver

- Short Story Collections:

- Carver, Raymond. What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Vintage, 1989.

- Carver, Raymond. Where I’m Calling From: New and Selected Stories. Vintage, 1989.

- Carver, Raymond. Cathedral. Vintage, 1989.

- Other Short Stories:

- Carver, Raymond. “Popular Mechanics.” (Available in various short story anthologies)

- Carver, Raymond. “Feathers.” (Available in various short story anthologies)

Thematic Pairings

- The Experience of Grief and Loss:

- Didion, Joan. The Year of Magical Thinking. Vintage, 2006. (Memoir)

- O’Brien, Tim. The Things They Carried. Mariner Books, 1990. (Short stories)

- Egan, Jennifer. A Visit from the Goon Squad. Anchor Books, 2011. (Novel)

Literary Minimalism

- Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises. Scribner, 2006. (Novel)

- Hemingway, Ernest. In Our Time. Scribner, 2003. (Short stories)

- Wolff, Tobias. This Boy’s Life. Grove Press, 2000. (Memoir)

- Ford, Richard. Rock Springs. Vintage, 1988. (Short stories)

Critical Analysis of Carver’s Work

- Nesset, Kirk. Stories of Raymond Carver: A Critical Study. Ohio University Press, 1995.

- Stull, William L. and Gentry, Marshall Bruce, eds. Conversations with Raymond Carver. University Press of Mississippi, 1990.

- Runyon, Randolph Paul. Reading Raymond Carver. Syracuse University Press, 1992.

Online Resources

- The International Raymond Carver Society: https://www.raymondcarverreview.org/the-organization

- Literary analysis and resources at LitCharts: https://www.litcharts.com/lit/a-small-good-thing