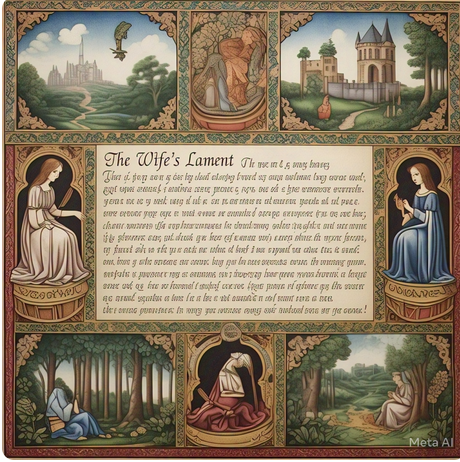

Introduction: “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

“The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy) first appeared in the Exeter Book around the 10th century, a manuscript published by an unknown scribe. The poem, often attributed to an anonymous author, presents a poignant reflection on grief, betrayal, and isolation through the voice of a woman whose husband has disappeared. The main ideas in the poem revolve around the themes of loss, longing, and emotional desolation as the wife recounts her heartache caused by her husband’s departure. The poem’s popularity can be attributed to its universal exploration of human suffering and its depiction of the powerful emotions associated with abandonment and separation. The text itself exemplifies the intensity of the wife’s loneliness and her internal battle with bitterness and unfulfilled love. As she laments, “I wander the ways all alone, under the oaks, around these graven walls” (35–36), the imagery of solitary wandering reinforces her emotional and physical isolation, making the poem resonate with readers across time as a vivid expression of enduring sorrow and the human condition.

Text: “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

She Laments

Oh, I can relate a tale right here, make myself

a map of miseries & trek right across.

I can say as much as you like —

how many gut-wretched nights ground over me

once I was a full-grown woman,

from early days to later nights,

never ever any more than right now. (1–4)

When is it never a struggle, a torment,

this arc of misfortune, mine alone?

It started when my man up and left,

who knows where, from his tribe

across the sleeplessness of waves.

I conceived a care at the dawning of dawn:

where did that man of a man go? (5–8)

Then I ferried myself forth, trying to dole

my part of the deal, a wretch drained of friends,

out a trembling need inside me. (9–10)

So it begins: his family starts scheming

moling up mountains of secret malice

to delve into our division,

make us survive along the widest wound of us —

could they be any more loathsome? —

and I became a longing inside. (11–14)

My love said to shack up in shadowy groves.

I was light in loved ones anyways in these lands,

in the loyalties of allegiance.

Therefore my brain brims with bitterness,

when I had located my likeness in him,

blessed with hard luck, heart-hollow,

painting over his intentions,

plotting the greatest of heists. (15–20)

Masked content, so many times

we swore that nothing but finality itself

could shave us in two, not them, not nothing.

The pivot was not long in coming,

it’s like, what did I hear a poet say once?

“as if it never was…”

that was our partnership. (21–25a)

Must I flag on flogging through feud,

far & near, of my many-beloved?

He was the one who said I should

go live in the woods or something,

sit under an oak-tree, in a gravel pit.

Let’s make it an earthen hall, musty & old,

where I’m all foreaten with longing:

Dales deep darkly, hills hedge me round,

fortresses of sharpness, bramble biting —

can a home be devoid of joy? (25b–32a)

For too many watches the wrathful from-ways

of my lord grabbed hold of me in this place.

Who could I count on? Buried.

Loved in their lives —

all they care about now are their beds. (32b–34)

Then I, when dawn still rumbles,

I wander the ways all alone,

under the oaks, around these graven walls.

There I can sit an endless summer day,

where I can rain me down for my wracking steps,

my collection of woes. So it goes —

never can I, in no wise, catch a break

from my cracking cares, nor this unfolding tear

that grasps me in this my entire life. (35–41)

The young should always keep their heart in check,

their inner kindlings cool, likewise

they must keep their faces frosty,

also the bubbling in their breast,

though crowded with swarming sorrows. (42–45a)

May all of his joys come at his own hand.

May his name be the name of infamy,

a snarl in faraway mouths, so that my good friend

will be sitting under a stony rain-break,

crusted by the gusty storms,

a man crushed at heart, flowing

in his own water, in his tearful timbering. (45b–50a)

That one, yeah, that man of mine

will drag his days under a mighty mind-caring.

He’ll remember every single morning

how full of pleasure was our home.

What woes are theirs who must

weather their worrying for love. (50b–53)

Annotations: “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

| Line(s) | Annotations (Simple English) | Literary Devices |

| 1–4 | The speaker says she can tell a story about her suffering, describing how her life has been full of misery from day to night. | Metaphor (“map of miseries”), Hyperbole (“gut-wretched nights”) |

| 5–8 | The speaker says that her troubles began when her husband left, and she is left wondering where he went. | Metaphor (“sleeplessness of waves”), Rhetorical Question (“where did that man of a man go?”) |

| 9–10 | She tried to deal with her problems but is left feeling drained and abandoned. | Alliteration (“ferried forth”), Metaphor (“a wretch drained of friends”) |

| 11–14 | The husband’s family started scheming to create a divide between them. The speaker became consumed by longing and bitterness. | Personification (“mountains of secret malice”), Metaphor (“I became a longing inside”) |

| 15–20 | Her love suggested they live in isolation, and the speaker is left with a sense of bitterness and confusion about his actions. | Symbolism (“shadowy groves”), Alliteration (“brain brims with bitterness”), Metaphor (“heart-hollow”) |

| 21–25a | The speaker reflects on their promises to stay together forever, but things eventually fell apart. | Irony (“as if it never was…”), Repetition (“nothing but finality”), Alliteration (“swore that nothing”) |

| 25b–32a | The speaker is told to live in a lonely, harsh place, and she reflects on how home can lack joy. | Imagery (“Dales deep darkly, hills hedge me round”), Metaphor (“fortresses of sharpness”) |

| 32b–34 | The speaker feels abandoned, with no one to rely on, and her husband’s wrath has affected her deeply. | Personification (“wrathful from-ways grabbed hold”), Hyperbole (“loved in their lives — all they care about now are their beds”) |

| 35–41 | She describes wandering alone, burdened by sorrow, and never finding relief from her troubles. | Alliteration (“wandering ways”), Metaphor (“cracking cares”), Repetition (“never can I, in no wise”) |

| 42–45a | The speaker advises the young to control their emotions, even when troubled by sorrow. | Advice (imperative tone), Metaphor (“inner kindlings cool”) |

| 45b–50a | The speaker curses her husband, wishing him a life of misery and regret, where he will remember their lost joy. | Irony (“name of infamy”), Symbolism (“stony rain-break”), Imagery (“gusty storms, a man crushed at heart”) |

| 50b–53 | She ends with a reflection on how her husband will eventually remember their home fondly, even as he suffers. | Irony (“weather their worrying for love”), Imagery (“crushed at heart”) |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

| Literary/Poetic Device | Example from Text | Explanation |

| Alliteration | “ferried forth” (9) | The repetition of consonant sounds at the beginning of words in close proximity. |

| Allusion | “as if it never was…” (21-25a) | A reference to something outside the text, suggesting a final end or irreversible loss. |

| Anaphora | “never can I, in no wise” (35-41) | The repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses for emphasis. |

| Antithesis | “what woes are theirs who must weather their worrying for love” (50b-53) | The juxtaposition of contrasting ideas, like suffering and love, to highlight the complexity of the speaker’s feelings. |

| Apostrophe | “Oh, I can relate a tale right here” (1) | The speaker directly addresses an abstract concept or absent figure, as though it could respond. |

| Assonance | “a man crushed at heart” (50b) | The repetition of vowel sounds within close proximity to create rhythm or enhance meaning. |

| Consonance | “wracking steps” (35) | The repetition of consonant sounds, especially at the end of words, to create a pleasing effect or emphasize a point. |

| Enjambment | “For too many watches the wrathful from-ways / of my lord grabbed hold of me in this place.” (32b–34) | The continuation of a sentence without a pause beyond the end of a line, couplet, or stanza. |

| Hyperbole | “gut-wretched nights” (1–4) | Exaggeration for emphasis or effect, such as describing the nights as “gut-wretched,” which exaggerates the sense of suffering. |

| Imagery | “Dales deep darkly, hills hedge me round” (25b–32a) | Descriptive language that appeals to the senses, creating a vivid mental picture. |

| Irony | “as if it never was…” (21–25a) | The expression of a sentiment that is opposite to what one would expect, like the idea that the speaker’s partnership is now forgotten, despite once being deeply significant. |

| Metaphor | “I can make myself a map of miseries” (1–4) | A comparison between two unlike things without using “like” or “as,” suggesting the speaker’s life is like a journey through suffering. |

| Onomatopoeia | “rain-break” (45b–50a) | A word that imitates a natural sound, enhancing the sensory experience of the text. |

| Oxymoron | “shadowy groves” (15–20) | The combination of two contradictory terms, like “shadowy” and “groves,” creating a mysterious or paradoxical effect. |

| Personification | “wrathful from-ways grabbed hold of me” (32b–34) | Giving human characteristics to non-human things, such as “wrathful” forces acting like a person who “grabs hold” of the speaker. |

| Rhetorical Question | “where did that man of a man go?” (5–8) | A question asked for effect rather than an answer, emphasizing the speaker’s confusion or distress. |

| Repetition | “never can I, in no wise” (35–41) | Repeating words or phrases to emphasize an idea or emotion, such as the speaker’s ongoing suffering. |

| Simile | “as if it never was…” (21–25a) | A comparison using “like” or “as,” comparing the former relationship to something that is no longer significant or real. |

| Symbolism | “oaks” (35–41) | The oak tree can symbolize strength and permanence, contrasting with the wife’s fragile and changing situation. |

| Tone | Bitter and sorrowful throughout the poem. | The general attitude of the speaker toward her situation, expressed through the choice of words and imagery. |

| Understatement | “I can relate a tale right here” (1) | A form of expression in which the speaker downplays the severity of the situation, suggesting a personal tragedy without immediately revealing its depth. |

Themes: “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

- Grief and Loss: The central theme of “The Wife’s Lament” is grief, particularly the profound sorrow experienced by the wife due to the absence of her husband. She expresses her mourning throughout the poem, emphasizing the depth of her pain and emotional turmoil. The speaker describes how her life has been marked by “gut-wretched nights” (1–4), a metaphor that conveys the intense physical and emotional anguish she endures. Her grief is compounded by the mystery of her husband’s departure, which she refers to as a deep and lasting wound: “Where did that man of a man go?” (5–8). The pain of not knowing where he has gone or why he left intensifies her suffering, and she is left to cope with this uncertainty in solitude. The idea of grief extends beyond the immediate absence of her husband and is reflected in the speaker’s isolation and emotional desolation, as she laments, “I wander the ways all alone” (35–36). This continuous journey of sorrow underscores the theme of unending grief.

- Isolation and Loneliness: The theme of isolation runs throughout the poem, highlighting the speaker’s sense of being alone both emotionally and physically. She begins by recounting her life’s misery and how she has been abandoned by her husband, which leads to her deep loneliness: “I can relate a tale right here, make myself / a map of miseries & trek right across” (1–4). This vivid image of navigating through a map of misery symbolizes the emotional journey the speaker is forced to endure in solitude. Her isolation becomes more apparent when she refers to her physical separation from loved ones, mentioning that she has become “a wretch drained of friends” (9–10), emphasizing the lack of support and companionship in her life. The metaphor of wandering “the ways all alone” (35–36) underlines her loneliness, as she reflects on her estrangement from her family and society. The emotional void left by her husband’s departure amplifies the physical loneliness she feels in her day-to-day existence.

- Betrayal and Deception: The theme of betrayal is explored through the actions of the husband and his family. The speaker’s sense of abandonment is compounded by the sense that his family was actively involved in causing the rupture between them. The wife perceives their actions as malicious, saying, “his family starts scheming / moling up mountains of secret malice” (11–12). This creates an image of hidden, devious actions that have contributed to her suffering. She feels betrayed not only by her husband’s departure but also by the betrayal of trust within the family unit, which makes her feel even more alienated. Furthermore, the wife reflects on how her husband’s promises and their past love now seem hollow: “We swore that nothing but finality itself / could shave us in two” (21–25a). The ironic twist here is that despite their vows, the relationship has been severed by both his disappearance and the betrayal she perceives from his family. This breach of trust is a powerful element of her grief and contributes to the bitterness that permeates the poem.

- Hope and Revenge: Despite the overwhelming sorrow, there is a subtle undercurrent of revenge and the desire for justice in the poem. The wife’s bitterness toward her husband reaches a point where she imagines his future suffering as a form of cosmic justice. She wishes that he will experience a life filled with regret and misfortune: “May his name be the name of infamy, / a snarl in faraway mouths” (45b–50a). This curse suggests that the wife harbors a desire for retribution, wishing that her husband’s life will be marked by as much pain and sorrow as hers has been. Her desire for revenge is not just emotional but also symbolic, representing the urge to restore balance or fairness after experiencing betrayal and suffering. In the final lines, she expresses the hope that her husband will remember their former joy together, but this reflection is tinged with irony as she wishes him to endure the same kind of emotional agony she has experienced: “He’ll remember every single morning / how full of pleasure was our home” (50b–53). This theme of vengeance intertwines with the poem’s exploration of grief, suggesting that while sorrow dominates the speaker’s life, a desire for justice lingers beneath the surface.

Literary Theories and “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

| Literary Theory | Explanation | References from the Poem |

| Feminist Criticism | Feminist criticism explores gender roles, identity, and the treatment of women in literature. In “The Wife’s Lament,” the speaker’s suffering and isolation reflect the societal and marital roles imposed on women. The poem highlights her emotional turmoil as she is abandoned and betrayed by her husband. | “I became a longing inside” (11–14), “I wander the ways all alone” (35–36). These lines highlight the emotional and physical isolation experienced by the wife, emphasizing her powerless position in a patriarchal society. |

| Historical Criticism | Historical criticism examines the social, political, and historical context of a work. The poem provides insight into the societal norms and gender expectations of Anglo-Saxon England, particularly regarding marriage and the treatment of women. The wife’s suffering reflects the emotional and social consequences of marital abandonment in this historical period. | “When is it never a struggle, a torment, / this arc of misfortune, mine alone?” (5–8), “His family starts scheming” (11–12). These references highlight the wife’s social and familial challenges, illustrating her historical role as a marginalized figure in her community. |

| Psychoanalytic Criticism | Psychoanalytic criticism delves into the unconscious motivations and psychological depth of characters. The wife’s emotions in the poem reflect deep psychological trauma due to abandonment and betrayal. Her self-inflicted isolation and bitterness suggest a fractured emotional state. | “heart-hollow” (15–20), “I conceived a care at the dawning of dawn” (5–8). These lines suggest an emotional emptiness and unresolved internal conflict, reflecting the wife’s psyche as she grapples with feelings of loss and abandonment. |

| Marxist Criticism | Marxist criticism focuses on class struggles, power dynamics, and material conditions. In “The Wife’s Lament,” the wife’s alienation can be seen as a result of familial and social power structures. Her lower status in the family and society exacerbates her emotional suffering. | “I was a full-grown woman” (1–4), “his family starts scheming” (11–12). These references reflect how the wife’s social position and lack of power in her marital relationship contribute to her sense of betrayal and isolation. |

Critical Questions about “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

- What role does the setting play in reflecting the speaker’s emotional state?

- The setting in “The Wife’s Lament” plays a crucial role in mirroring the speaker’s emotional desolation and isolation. The poem’s natural landscape—described as dark, remote, and hostile—symbolizes the speaker’s inner turmoil and grief. Phrases such as “Dales deep darkly, hills hedge me round” (25b–32a) evoke an image of a harsh, unwelcoming environment, underscoring the speaker’s sense of being trapped in her emotional suffering. The setting of “under the oaks, around these graven walls” (35–36) further emphasizes the speaker’s loneliness and emotional imprisonment. The use of nature as a reflection of the speaker’s feelings highlights her separation not just from her husband, but from the world and society, portraying her emotional landscape as barren and unforgiving. The natural world is not a source of comfort or solace but an extension of her grief, amplifying her feelings of abandonment and isolation.

- How does the speaker’s sense of betrayal affect her understanding of love and loyalty?

- The speaker’s sense of betrayal deeply influences her perception of love and loyalty, turning these concepts into sources of bitterness and disillusionment. Initially, love between the speaker and her husband seemed to be grounded in mutual loyalty, as reflected in their promises: “We swore that nothing but finality itself / could shave us in two” (21–25a). However, the betrayal she experiences when her husband abandons her—and the scheming of his family that follows—shatters her idealistic understanding of love. The concept of loyalty, which once seemed unwavering, is exposed as fragile and easily broken by external forces. The speaker expresses this disillusionment when she reflects on how their partnership has collapsed, stating that it feels “as if it never was…” (21–25a), indicating that their vows now seem meaningless in light of her abandonment. This transformation of love from something sacred to a source of pain highlights the depth of her betrayal and the emotional cost of broken promises.

- What is the significance of the speaker’s desire for revenge, and what does it reveal about her emotional state?

- The speaker’s desire for revenge is a critical aspect of her emotional response to the suffering she endures. Although the poem predominantly conveys sorrow and longing, her expression of vengeance reveals the intensity of her emotional distress. She wishes for her husband to experience as much misery as she has, hoping that his name will become one of “infamy” and that he will “sit under a stony rain-break” (45b–50a). This desire for retribution suggests that the speaker is not only grieving her abandonment but is also grappling with feelings of anger and injustice. Her revenge is not merely a wish for punishment but a means of restoring balance to her world, where she has been wronged. This emotional complexity shows that, while grief dominates her experience, anger and a desire for justice are also integral to her emotional state. The speaker’s curse reveals how deeply she feels the betrayal and how this betrayal distorts her perception of love and retribution.

- How does the poem explore the theme of loneliness and its impact on the speaker?

- Loneliness is a pervasive theme in “The Wife’s Lament,” with the speaker repeatedly emphasizing her isolation and emotional emptiness. The poem begins with the speaker’s assertion that she has endured “gut-wretched nights” (1–4), immediately framing her experience as one of prolonged suffering and solitude. She explicitly states, “I wander the ways all alone” (35–36), reinforcing her sense of being abandoned, both physically and emotionally. The poem explores how this loneliness affects her on a profound level, leaving her “heart-hollow” (15–20) and full of longing for a companionship that is no longer present. The wife’s solitude is compounded by her physical separation from others, with no allies to turn to, as seen in her lament, “Who could I count on? Buried” (32b–34). The impact of loneliness is not just emotional; it is physical and existential, as the speaker reflects on the absence of any comfort or support in her life. This isolation shapes her worldview, turning her into a figure whose only solace is in her own grief and bitterness. Through the speaker’s intense loneliness, the poem underscores how isolation can erode one’s sense of self and lead to a desolate emotional state.

Literary Works Similar to “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

- “The Seafarer” (Anonymous)

Like “The Wife’s Lament,” this poem explores themes of isolation, longing, and the emotional impact of separation, especially in the context of exile and loneliness. - “The Wanderer” (Anonymous)

Similar to “The Wife’s Lament,” this poem delves into the sorrow and solitude experienced by a lone individual, reflecting on past joys and the deep pain of losing those connections. - “The Husband’s Message” (Anonymous)

Both poems focus on the experience of emotional separation, with “The Husband’s Message” portraying the speaker’s longing and a sense of distance between lovers, akin to the wife’s sorrow in “The Wife’s Lament.” - “Fair Elanor” by William Blake

Much like “The Wife’s Lament,” Blake’s poem portrays the pain of emotional separation and the inner suffering of the speaker, emphasizing feelings of abandonment and longing. - “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

While different in style, “The Raven” shares a thematic similarity with “The Wife’s Lament” in its portrayal of grief, loneliness, and the haunting nature of emotional loss.

Representative Quotations of “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “I can relate a tale right here” (1–4) | The speaker begins by expressing her emotional pain, offering to tell her story of suffering. | Psychoanalytic Criticism: This reflects the speaker’s need to externalize her pain, an act of self-therapy through narration. |

| “gut-wretched nights” (1–4) | Describes the intense suffering and emotional distress the speaker experiences during the long nights of her loneliness. | Feminist Criticism: Highlights the emotional and physical toll of isolation, especially on women in a patriarchal society. |

| “Where did that man of a man go?” (5–8) | The speaker questions her husband’s departure, reflecting her confusion and pain over his abandonment. | Historical Criticism: The historical context of marital roles and abandonment in early Anglo-Saxon society informs the wife’s pain. |

| “I became a longing inside” (11–14) | The speaker reflects on how her emotional state has transformed into longing, marking the depth of her grief. | Feminist Criticism: The internalization of longing signifies a lack of agency and power, as the speaker is consumed by her unrequited desire. |

| “His family starts scheming” (11–12) | The wife accuses her husband’s family of conspiring against her and their relationship, intensifying her sense of betrayal. | Marxist Criticism: This reflects power struggles within the family, where the wife is oppressed and manipulated by those with power. |

| “We swore that nothing but finality itself / could shave us in two” (21–25a) | The speaker recalls the promises made between her and her husband, which now seem empty and meaningless after his betrayal. | New Historicism: The ideals of loyalty and commitment were integral in the social fabric of the time, but they are shown to be fragile. |

| “I wander the ways all alone” (35–36) | The speaker describes her physical and emotional isolation as she roams the landscape, deepening her sense of abandonment. | Ecocriticism: The natural world mirrors the speaker’s emotional landscape, emphasizing the harshness and loneliness of her situation. |

| “heart-hollow” (15–20) | A metaphor expressing the emotional void the speaker feels due to the loss of her husband and the emotional weight of her situation. | Psychoanalytic Criticism: The phrase “heart-hollow” represents a psychological wound, an emptiness caused by emotional trauma. |

| “May his name be the name of infamy” (45b–50a) | The speaker curses her husband, wishing that his life be marked by infamy, reflecting a desire for revenge and justice. | Feminist Criticism: The expression of vengeance represents the reclaiming of power by the speaker in response to patriarchal betrayal. |

| “I was a full-grown woman” (1–4) | The speaker reflects on her past as a woman of strength, before being reduced to a victim of circumstances and betrayal. | Structuralist Feminism: This highlights the transition from agency to passivity, with the wife moving from strength to a powerless state due to societal constraints. |

Suggested Readings: “The Wife’s Lament” (Anglo-Saxon Elegy)

- Bray, Dorothy Ann. “A Woman’s Loss and Lamentation: Heledd’s Song and” The Wife’s Lament”.” Neophilologus 79.1 (1995): 147.

- Ward, J. A. “‘The Wife’s Lament’: An Interpretation.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 59, no. 1, 1960, pp. 26–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27707403. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

- Rissanen, Matti. “THE THEME OF ‘EXILE’ IN ‘THE WIFE’S LAMENT.'” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, vol. 70, no. 1, 1969, pp. 90–104. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43342501. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

- Stevick, Robert D. “Formal Aspects of ‘The Wife’s Lament.'” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 59, no. 1, 1960, pp. 21–25. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27707402. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

- Stevens, Martin. “THE NARRATOR OF ‘THE WIFE’S LAMENT.'” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, vol. 69, no. 1, 1968, pp. 72–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43342401. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.