Introduction: “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

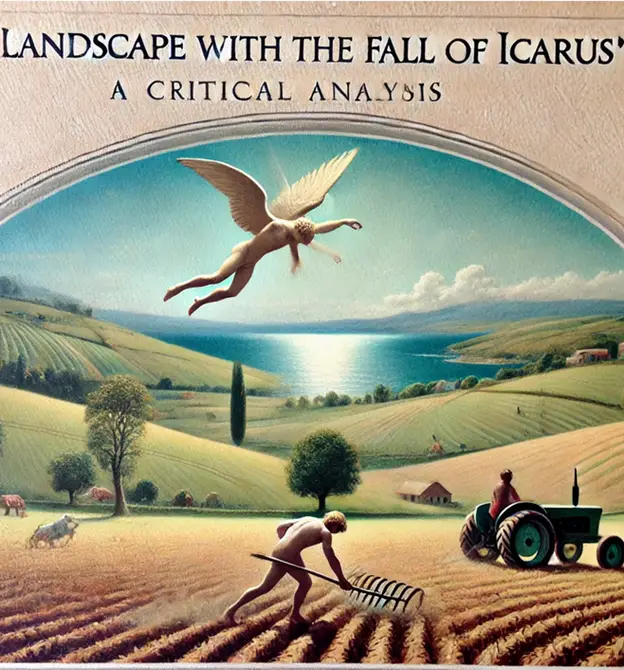

“Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams first appeared in 1926 in the collection In the American Grain. This poem is known for its imagistic style and minimalist approach. Williams presents a seemingly ordinary landscape, yet subtly incorporates the mythological tale of Icarus’s tragic fall. The poem’s qualities include its concise language, vivid imagery, and ironic juxtaposition of the mundane and the monumental. The main idea is to suggest that even the most dramatic events can pass unnoticed in the vastness of the natural world, highlighting the indifference of nature to human affairs.

Text: “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

near

the edge of the sea

concerned

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings’ wax

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

Annotations: “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

| Line | Text | Annotation |

| 1 | “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams | The title references both the poem by Williams and the famous painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The title sets the context for a reflection on the mythological event of Icarus’s fall from the sky. |

| 2 | “According to Brueghel” | The poem begins with a reference to Bruegel, indicating that the perspective being discussed is derived from the painting “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.” This signals the blending of visual art and poetry. |

| 3 | “when Icarus fell” | This line introduces the mythological event of Icarus falling into the sea, which is central to the story. The word “fell” is understated, emphasizing the insignificance of the event in the grander scene. |

| 4 | “it was spring” | The mention of spring suggests a time of renewal and life, contrasting sharply with the tragedy of Icarus’s fall. This contrast highlights the indifference of nature to individual human suffering. |

| 5 | “a farmer was ploughing” | The farmer, a central figure in Bruegel’s painting, symbolizes the everyday life that continues unaffected by the extraordinary event happening nearby. His ploughing represents routine and the cycle of life. |

| 6 | “his field” | The farmer’s focus on his field emphasizes his detachment from the dramatic event. It suggests a narrow focus on personal concerns, oblivious to the broader world. |

| 7-8 | “the whole pageantry of the year was awake tingling” | These lines describe the vibrancy and activity of the natural world. “Pageantry” suggests a grand, ongoing display of life, again underscoring the indifference to Icarus’s fate. |

| 9-10 | “near the edge of the sea” | The location near the sea introduces the setting where Icarus falls, yet the placement of this detail in the middle of the stanza keeps the focus on the landscape rather than the tragic event. |

| 11-12 | “concerned with itself” | Nature is depicted as self-absorbed, further emphasizing the theme of indifference. The world is “concerned with itself,” not with the fall of Icarus, highlighting the theme of human insignificance in the face of nature. |

| 13-14 | “sweating in the sun” | This line describes the farmer’s physical labor, showing the intensity of his work. The imagery of “sweating” and “sun” suggests the harshness of life and the relentless march of time, unconcerned with individual tragedy. |

| 15-16 | “that melted the wings’ wax” | Here, the myth is referenced directly. The sun, a natural force, causes the wax holding Icarus’s wings together to melt, leading to his fall. This underscores the inevitable consequence of Icarus’s hubris and the indifference of nature. |

| 17 | “unsignificantly” | This word encapsulates the poem’s central theme: Icarus’s fall is insignificant in the grand scheme of things. This downplays the drama of the myth, emphasizing the triviality of individual human events. |

| 18 | “off the coast” | Icarus’s fall occurs “off the coast,” away from the main action of the scene, reinforcing the idea that it is peripheral to the concerns of the world. |

| 19-20 | “there was a splash quite unnoticed” | The splash, a metaphor for Icarus’s fall, goes “unnoticed,” further emphasizing the world’s indifference to individual tragedy. This line mirrors the smallness of Icarus in Bruegel’s painting, barely a footnote in the larger scene. |

| 21-22 | “this was Icarus drowning” | The final line succinctly states what happened to Icarus, bringing the focus back to the individual tragedy. The flat, unemotional tone of the line underscores the poem’s theme of the indifference of the world to personal suffering. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

| Device | Definition | Example from the Poem | Explanation |

| Alliteration | The repetition of initial consonant sounds in nearby words. | “pageantry of the year was awake tingling” | The repetition of the ‘w’ sound in “was” and “awake” and the ‘t’ sound in “tingling” creates a rhythmic effect, emphasizing the vibrancy of nature. |

| Allusion | An indirect reference to a person, event, or thing, typically from literature, history, or mythology. | “According to Brueghel” | The poem alludes to Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” creating a connection between visual art and poetry and setting the tone for the poem’s themes. |

| Ambiguity | A word, phrase, or statement that has multiple meanings or interpretations. | “unsignificantly” | The word “unsignificantly” suggests both the insignificance of Icarus’s fall and the indifference of the world, allowing for multiple interpretations of the event’s importance. |

| Anaphora | The repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses or lines. | “the whole pageantry of the year was awake tingling” | The repetition of “the” at the beginning of consecutive lines creates emphasis and rhythm, drawing attention to the ongoing activity in the landscape. |

| Assonance | The repetition of vowel sounds within nearby words. | “sweating in the sun” | The repetition of the ‘e’ sound in “sweating” and “in” creates a melodic quality and emphasizes the harshness of the sun and labor. |

| Caesura | A pause in a line of poetry, typically marked by punctuation. | “unsignificantly / off the coast” | The caesura after “unsignificantly” creates a pause, emphasizing the insignificance of Icarus’s fall and the separation between human life and the natural world. |

| Contrast | The juxtaposition of opposing elements to highlight differences. | “spring” and “Icarus fell” | The contrast between the renewal of spring and the tragedy of Icarus’s fall highlights the indifference of nature to human suffering. |

| Consonance | The repetition of consonant sounds within or at the end of words. | “concerned with itself” | The repetition of the ‘c’ and ‘n’ sounds in “concerned” and “itself” adds to the rhythmic quality of the line, emphasizing the self-absorption of nature. |

| Enjambment | The continuation of a sentence or clause across a line break. | “when Icarus fell / it was spring” | The enjambment between these lines carries the reader’s attention from one line to the next, reflecting the seamless continuity of the natural world despite Icarus’s fall. |

| Imagery | The use of vivid and descriptive language to create sensory experiences for the reader. | “near the edge of the sea” | This imagery paints a vivid picture of the setting, allowing the reader to visualize the serene landscape in contrast to the tragedy occurring nearby. |

| Irony | A contrast between expectation and reality, often highlighting a discrepancy. | “there was a splash quite unnoticed” | The irony lies in the fact that a dramatic event, Icarus’s fall, is barely noticed, highlighting the poem’s theme of indifference. |

| Juxtaposition | Placing two or more elements side by side to compare or contrast them. | “a farmer was ploughing” vs. “Icarus drowning” | The juxtaposition of the farmer’s mundane activity with Icarus’s tragic drowning emphasizes the contrast between ordinary life and extraordinary events. |

| Metaphor | A figure of speech that compares two unlike things by stating that one is the other. | “the whole pageantry of the year” | The “pageantry of the year” is a metaphor comparing the natural cycle of seasons to a grand, ongoing display, highlighting the vibrancy of life. |

| Motif | A recurring theme, subject, or idea in a literary work. | Indifference of nature | The motif of nature’s indifference to human events is repeated throughout the poem, reinforcing the central theme that life continues unaffected by individual tragedies. |

| Paradox | A statement that contradicts itself but may reveal a deeper truth. | “unsignificantly / off the coast” | The paradox lies in the idea that such a significant event (Icarus’s fall) is described as insignificant, reflecting the poem’s theme of trivializing individual suffering in the grand scheme of things. |

| Personification | The attribution of human characteristics to non-human entities. | “the whole pageantry of the year was awake” | The year is personified as being “awake,” attributing human-like consciousness to the natural world, emphasizing its vibrant activity. |

| Repetition | The use of the same word or phrase multiple times to emphasize a concept. | “concerned with itself” | The repetition of “itself” emphasizes the self-absorption of the natural world, highlighting its indifference to Icarus’s fall. |

| Simile | A figure of speech comparing two unlike things using “like” or “as.” | Not directly used in this poem | While similes are not explicitly present in this poem, the poem’s vivid imagery invites comparisons, as when one might imagine Icarus’s wings melting “like wax” in the sun, which alludes to the original myth. |

| Symbolism | The use of symbols to represent ideas or qualities beyond their literal meaning. | “Icarus” | Icarus symbolizes human ambition and hubris, as well as the tragic consequences of overreaching. His fall represents the inevitable failure of those who attempt to transcend their human limitations. |

| Tone | The attitude or mood conveyed by the poet through word choice and style. | Detached, indifferent | The tone of the poem is detached and indifferent, reflecting the overall theme that the world remains unaffected by individual human tragedies, such as the fall of Icarus. |

Themes: “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

- Indifference of Nature: One of the central themes of the poem is the indifference of nature to human suffering and tragedy. Williams emphasizes this by focusing on the pastoral landscape, where “the whole pageantry of the year was awake tingling” (lines 7-8), continuing its course without acknowledging Icarus’s fall. The farmer ploughing his field, “concerned with itself” (line 12), symbolizes the broader natural world that remains unaffected by the dramatic event of Icarus’s descent. This indifference underscores the insignificance of individual human experiences in the grander scheme of nature.

- Human Obliviousness: The poem also explores the theme of human obliviousness to the suffering of others. The farmer, who is “sweating in the sun” (line 13) as he goes about his daily work, is completely unaware of the nearby tragedy. The “splash quite unnoticed” (line 20) as Icarus drowns highlights how people can be so absorbed in their own lives and routines that they fail to notice or acknowledge the misfortunes of others. This theme suggests a commentary on human nature’s tendency to overlook events that do not directly affect one’s immediate concerns.

- The Trivialization of Human Ambition: Icarus’s fall represents the consequences of human ambition and the pursuit of greatness, but the poem trivializes this ambition by placing it in the context of everyday life. The melting of the “wings’ wax” (line 15) is described as occurring “unsignificantly” (line 17), diminishing the importance of the mythological event. Williams’s portrayal of Icarus’s fall as a minor, almost irrelevant occurrence contrasts sharply with the traditional heroic narrative, suggesting that individual ambitions are often insignificant in the larger context of the world.

- The Continuity of Life: Another theme in the poem is the continuity of life, regardless of individual tragedies. While Icarus falls and drowns, life goes on; the farmer continues plowing his field, and nature remains vibrant and active. The “pageantry of the year” (line 7) and the farmer’s steady work suggest that the cycles of life persist without interruption, despite the occasional disruptions caused by human events. This theme highlights the resilience and persistence of life in the face of death and loss, underscoring the idea that the world continues to turn, indifferent to individual fates.

Literary Theories and “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

- New Criticism

- New Criticism emphasizes close reading and analysis of the text itself, focusing on its structure, form, and meaning without considering external contexts like the author’s biography or historical background. Applying New Criticism to “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” one might examine the poem’s use of imagery, contrast, and tone to uncover its deeper meanings. For example, the contrast between the vibrant spring landscape and Icarus’s unnoticed fall (“there was a splash quite unnoticed” – line 20) highlights the theme of human insignificance in the face of nature’s indifference. The poem’s structure, with its enjambment and sparse punctuation, reflects the continuous flow of life, further reinforcing the idea that individual tragedies are merely small disruptions in the larger, ongoing cycle of existence.

- Mythological Criticism

- Mythological criticism explores how classical myths are used in literature to convey universal themes and human experiences. In “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” Williams draws on the Greek myth of Icarus, who falls into the sea after flying too close to the sun. This myth is reinterpreted in the poem to emphasize the trivialization of human ambition and the inevitable consequences of hubris. The reference to “the wings’ wax” melting (line 15) serves as a reminder of Icarus’s overreaching, while the poem’s focus on the mundane activities of the farmer (“a farmer was ploughing / his field” – lines 5-6) contrasts the mythological with the everyday, suggesting that even the most dramatic human endeavors are ultimately insignificant in the broader context of life and nature.

- Ecocriticism

- Ecocriticism examines the relationship between literature and the natural environment, often focusing on how nature is represented and how human interactions with the environment are portrayed. In “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” the natural world is depicted as indifferent to human events, as seen in the description of the landscape that continues to “awake tingling” (line 8) despite Icarus’s fall. The farmer’s connection to the land through his work (“sweating in the sun” – line 13) contrasts sharply with Icarus’s failed attempt to transcend natural limits, symbolized by his fall. The poem critiques the human tendency to overlook nature’s power and persistence, suggesting that nature remains unconcerned with human tragedies and ambitions, which are fleeting in comparison to the enduring cycles of the natural world.

Critical Questions about “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

- How does Williams’s use of imagery contribute to the poem’s theme of indifference?

- Williams employs vivid imagery to create a seemingly ordinary landscape, focusing on the mundane details of the farmer’s activities and the natural beauty of the scene. This contrast with the tragic event of Icarus’s fall emphasizes the indifference of the natural world to human suffering. The image of the farmer “concerned with itself” reinforces the self-centered nature of humanity and the way in which we often overlook the tragedies of others. The juxtaposition of the ordinary and the extraordinary creates a sense of dissonance, highlighting the disconnect between the human experience and the larger forces of nature.

- What is the significance of the poem’s title, “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus”?

- The title suggests a juxtaposition between the ordinary landscape and the extraordinary event of Icarus’s fall. By placing the mythological figure within a realistic setting, Williams emphasizes the contrast between the timeless nature of myth and the fleetingness of human life. The title also implies that the tragic event of Icarus’s fall is merely a minor detail in the larger context of the natural world. This suggests a sense of perspective and the importance of considering the broader context when evaluating individual events.

- How does the poem’s minimalist style enhance its impact?

- Williams’s use of concise language and simple sentence structure creates a sense of immediacy and directness, allowing the reader to focus on the essential elements of the scene. By avoiding unnecessary embellishments, the poet emphasizes the contrast between the grandeur of the mythological tale and the mundane reality of the landscape. The minimalist style also reinforces the theme of indifference, as the poet suggests that even the most dramatic events can be reduced to a simple, factual statement.

- What is the significance of the poem’s ending, where Icarus “drowning” is described as “unsignificantly off the coast”?

- The phrase “unsignificantly off the coast” underscores the insignificance of Icarus’s tragic death in the vastness of the natural world. The image of Icarus drowning “quite unnoticed” emphasizes the indifference of both nature and humanity to the individual’s suffering. This ending reinforces the poem’s central theme of the human condition as a mere blip in the grand scheme of things. It also suggests a sense of futility and the limitations of human agency in the face of the indifferent forces of nature.

Literary Works Similar to “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

· “Musée des Beaux Arts” by W.H. Auden

- Similarity: This poem, like Williams’ work, reflects on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.” Auden explores the theme of human suffering being ignored by the rest of the world, much like how the farmer in Williams’ poem is oblivious to Icarus’s fall.

· “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Similarity: Shelley’s poem similarly addresses the theme of the insignificance of human achievements in the grand scheme of time. The once-great statue of Ozymandias lies in ruins in the desert, unnoticed by the world, much like Icarus’s unnoticed fall in Williams’ poem.

· “The Second Coming” by W.B. Yeats

- Similarity: Yeats’ poem, while apocalyptic in tone, shares a thematic focus on the insignificance and fragility of human efforts in the face of larger, uncontrollable forces. Both poems depict a world indifferent to human ambition and suffering.

· “The Hollow Men” by T.S. Eliot

- Similarity: Eliot’s poem, with its exploration of existential despair and the futility of human endeavor, resonates with the themes of insignificance and indifference found in Williams’ depiction of Icarus’s unnoticed fall.

· “Out, Out—” by Robert Frost

- Similarity: Frost’s poem depicts a tragic event—a boy’s accidental death—that is quickly followed by the resumption of normal life by those around him, echoing the theme in Williams’ poem of human suffering being overlooked by the ongoing rhythms of daily life.

Suggested Readings: “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

- Bruegel, Pieter the Elder. Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. c. 1560. Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

- Fisch, Audrey A. “The Fall of Icarus: An Analysis of W. H. Auden’s Poem and Its Connection to the Painting.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 34, no. 2, 1988, pp. 171-183. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/441730.

- Hamilton, Ian. The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry in English. Oxford UP, 1994.

- Jarrell, Randall. “The Icarus Complex.” Poetry and the Age. Wesleyan UP, 1953, pp. 130-135.

- Miller, J. Hillis. “The Function of Art in the Poetry of William Carlos Williams.” ELH, vol. 24, no. 1, 1957, pp. 66-76. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2872091.

- Pound, Ezra. “Imagisme.” Poetry, vol. 1, no. 6, 1913, pp. 200-206. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20569730.

- Wagner, Linda W. “The Visual Image in the Poetry of William Carlos Williams.” American Literature, vol. 38, no. 3, 1966, pp. 281-294. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2922476

Representative Quotations of “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by William Carlos Williams

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “According to Brueghel” | The poem begins with a reference to the Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel, suggesting a connection to art history. | Intertextuality: The relationship between a text and other texts. |

| “when Icarus fell” | The poem introduces the central theme of Icarus’s tragic fall. | Mythology: The study of myths and legends. |

| “it was spring” | The poem establishes a temporal setting, suggesting a time of renewal and growth. | Symbolism: The use of objects or events to represent abstract ideas. |

| “a farmer was ploughing his field” | The poem presents a mundane scene of rural life. | Realism: A literary movement that aimed to depict life realistically. |

| “the whole pageantry of the year was awake tingling” | The poem describes the vibrant beauty of spring. | Imagery: The use of vivid language to create mental images. |

| “near the edge of the sea” | The poem establishes a geographical setting. | Naturalism: A literary movement that emphasized the influence of natural forces on human life. |

| “concerned with itself” | The poem suggests that the farmer is self-centered and oblivious to the larger world. | Individualism: The belief that individuals should pursue their own goals and interests. |

| “sweating in the sun that melted the wings’ wax” | The poem describes the cause of Icarus’s fall. | Causation: The relationship between cause and effect. |

| “unsignificantly off the coast” | The poem suggests that Icarus’s fall is insignificant in the grand scheme of things. | Relativism: The belief that truth is relative and depends on the perspective of the observer. |

| “there was a splash quite unnoticed” | The poem emphasizes the indifference of the world to Icarus’s tragedy. | Indifference: The lack of interest or concern. |