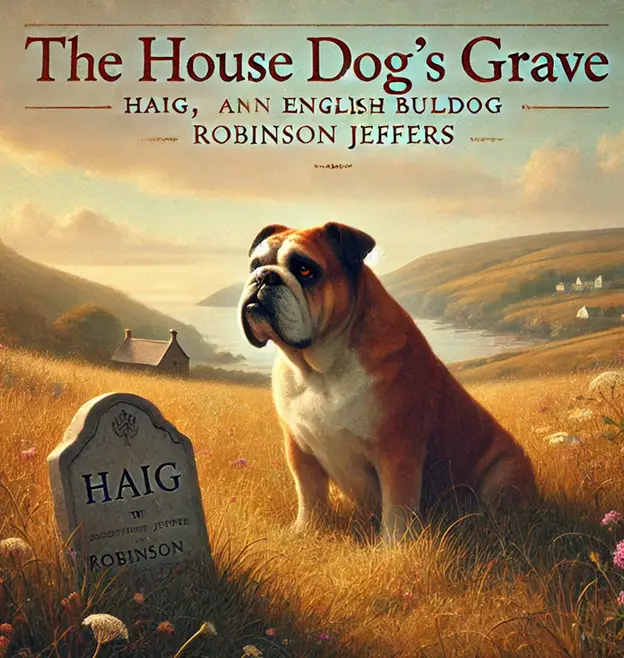

Introduction: “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

“The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers first appeared in the year 1941 in his collection Be Angry at the Sun and Other Poems. The poem is a poignant and intimate elegy for the poet’s beloved bulldog, Haig. Jeffers employs a unique perspective, writing the poem from the dog’s point of view, creating a deeply empathetic and heart-wrenching tone. The piece is characterized by its simplicity, directness, and profound sense of loss, as the dog reflects on its life and its enduring love for its human companions.

Text: “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

I’ve changed my ways a little; I cannot now

Run with you in the evenings along the shore,

Except in a kind of dream; and you, if you dream a moment,

You see me there.

So leave awhile the paw-marks on the front door

Where I used to scratch to go out or in,

And you’d soon open; leave on the kitchen floor

The marks of my drinking-pan.

I cannot lie by your fire as I used to do

On the warm stone,

Nor at the foot of your bed; no, all the night through

I lie alone.

But your kind thought has laid me less than six feet

Outside your window where firelight so often plays,

And where you sit to read–and I fear often grieving for me–

Every night your lamplight lies on my place.

You, man and woman, live so long, it is hard

To think of you ever dying

A little dog would get tired, living so long.

I hope than when you are lying

Under the ground like me your lives will appear

As good and joyful as mine.

No, dear, that’s too much hope: you are not so well cared for

As I have been.

And never have known the passionate undivided

Fidelities that I knew.

Your minds are perhaps too active, too many-sided. . . .

But to me you were true.

You were never masters, but friends. I was your friend.

I loved you well, and was loved. Deep love endures

To the end and far past the end. If this is my end,

I am not lonely. I am not afraid. I am still yours.

Annotations: “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

| Stanza | Text | Annotation |

| 1 | I’ve changed my ways a little; I cannot now Run with you in the evenings along the shore, Except in a kind of dream; and you, if you dream a moment, You see me there. | The speaker, a deceased dog, reflects on how its life has changed since death. The dog acknowledges it can no longer physically accompany its owners but suggests it can still be with them in dreams, indicating a lingering spiritual presence. |

| 2 | So leave awhile the paw-marks on the front door Where I used to scratch to go out or in, And you’d soon open; leave on the kitchen floor The marks of my drinking-pan. | The dog reminisces about the physical traces it left behind, such as paw marks and scratches, as a way of remembering the connection it had with its owners. These marks are symbolic of the dog’s life and presence in the home. |

| 3 | I cannot lie by your fire as I used to do On the warm stone, Nor at the foot of your bed; no, all the night through I lie alone. | The dog expresses a sense of loss and loneliness after death, acknowledging that it can no longer enjoy the warmth of the fire or the companionship of lying by its owners at night. The imagery conveys the comfort and bond it shared with its family during life. |

| 4 | But your kind thought has laid me less than six feet Outside your window where firelight so often plays, And where you sit to read–and I fear often grieving for me– Every night your lamplight lies on my place. | The dog recognizes its final resting place is close to its owners, buried just outside their window. The mention of the firelight and lamplight symbolizes the warmth and care the dog still feels from its owners, despite the physical separation caused by death. |

| 5 | You, man and woman, live so long, it is hard To think of you ever dying A little dog would get tired, living so long. I hope than when you are lying | The dog reflects on the difference in lifespans between humans and dogs, expressing a sentiment that a dog’s shorter life may be a blessing in disguise. The dog’s hope for its owners is that they, too, will find peace and fulfillment in the afterlife. |

| 6 | Under the ground like me your lives will appear As good and joyful as mine. No, dear, that’s too much hope: you are not so well cared for As I have been. | The dog realizes that the care and simplicity of its life may have been easier to achieve than the complexities of human life. It acknowledges that humans face more challenges and may not experience the same contentment or care that it had as a beloved pet. |

| 7 | And never have known the passionate undivided Fidelities that I knew. Your minds are perhaps too active, too many-sided. . . . But to me you were true. | The dog reflects on the pure, unwavering loyalty it experienced and gave during its life, contrasting it with the more complex and divided loyalties of humans. However, it acknowledges the genuine love and fidelity it received from its owners. |

| 8 | You were never masters, but friends. I was your friend. I loved you well, and was loved. Deep love endures To the end and far past the end. If this is my end, I am not lonely. I am not afraid. I am still yours. | The dog concludes by affirming the deep, mutual bond it shared with its owners, emphasizing that they were not just masters but true friends. It expresses a sense of peace and acceptance in death, confident that the love it experienced transcends even the end of life. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

| Device | Definition | Example | Explanation |

| Apostrophe | Direct address to an absent or imaginary person or thing | “You, man and woman, live so long” | Creates a sense of intimacy and emotional connection. |

| Enjambment | Continuing a sentence or phrase beyond the end of a line | “Run with you in the evenings along the shore,<br>Except in a kind of dream” | Mimics the flow of thoughts and memories. |

| Imagery | Vivid descriptions that appeal to the senses | “firelight so often plays” | Creates a warm and comforting atmosphere. |

| Irony | A contrast between what is expected and what actually happens | “I hope than when you are lying<br>Under the ground like me your lives will appear<br>As good and joyful as mine.” | Highlights the disparity between human and canine experiences. |

| Metaphor | A comparison between two unlike things without using “like” or “as” | “I am not lonely. I am not afraid. I am still yours.” | Reinforces the enduring bond between the dog and its owners. |

| Personification | Giving human qualities to non-human things | “I cannot lie by your fire as I used to do” | Creates empathy for the dog and its loss. |

| Repetition | Repeating words or phrases for emphasis | “I cannot” | Emphasizes the dog’s limitations in its new state. |

| Simile | A comparison between two unlike things using “like” or “as” | “Except in a kind of dream” | Creates a sense of longing and wistfulness. |

| Symbolism | The use of objects or actions to represent ideas or qualities | “paw-marks” | Symbolizes the dog’s physical presence and its absence. |

| Tone | The author’s attitude toward the subject matter | Melancholy and loving | Conveys the deep sorrow and affection for the dog. |

| Understatement | Presenting something as less important than it actually is | “I’ve changed my ways a little” | Understates the profound impact of the dog’s death. |

| Blank verse | Unrhymed poetry written in iambic pentameter | Throughout the poem | Creates a natural and conversational tone. |

| Elegy | A poem that laments the death of someone | Entire poem | Expresses grief and sorrow for the loss of the dog. |

| Free verse | Poetry that does not follow a regular rhyme scheme or meter | Throughout the poem | Allows for flexibility in expressing emotions. |

| Speaker | The voice that tells the story | The dog | Creates a unique and intimate perspective. |

| Soliloquy | A long speech by a character expressing their thoughts | Entire poem | Offers a deep insight into the dog’s feelings and memories. |

| Theme | The central idea or message of the poem | The enduring nature of love and loss | Explores the complexities of human-animal relationships. |

| Verisimilitude | The appearance of being true or real | Detailed descriptions of the dog’s life | Creates a sense of authenticity and believability. |

| Voice | The distinctive style and tone of a writer | Intimate and reflective | Reflects the dog’s perspective and emotions. |

Themes: “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

- Theme 1: Enduring Love: The poem emphasizes the enduring love between the dog and its owners. Lines like “I loved you well, and was loved. Deep love endures / To the end and far past the end” and “I am not lonely. I am not afraid. I am still yours” express the dog’s unwavering devotion and the belief that their bond transcends death. Even though the dog has passed away, its love for its owners remains strong.

- Theme 2: Loss and Grief: The poem is filled with a sense of loss and grief. Lines like “I cannot now / Run with you in the evenings along the shore” and “So leave awhile the paw-marks on the front door” highlight the dog’s absence and the routines disrupted by its death. The speaker’s longing for their past life together is evident throughout the poem. The poem creates a sense of melancholy and sorrow for the loss of the beloved dog.

- Theme 3: Loyalty and Fidelity: The poem portrays the dog’s unwavering loyalty and fidelity. Lines like “But to me you were true. / You were never masters, but friends. I was your friend” emphasize the dog’s unconditional love and its perception of their relationship as one of friendship rather than servitude. The dog sees its owners as companions rather than masters, and its devotion to them is absolute.

- Theme 4: Mortality and the Contrast Between Human and Animal Lives: The poem explores the contrast between human and animal lifespans. Lines like “You, man and woman, live so long, it is hard / To think of you ever dying” and “A little dog would get tired, living so long” highlight the dog’s acceptance of its own mortality and its concern for its owners’ well-being in the face of their inevitable deaths. The dog recognizes that humans live much longer lives than dogs, and it expresses a kind of concern for what will happen to its owners when they eventually die.

Literary Theories and “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

| Literary Theory | Application to “The House Dog’s Grave” | Critique |

| Ecocriticism | Focuses on the relationship between literature and the natural world. Jeffers’ poem emphasizes the connection between humans, animals, and the environment. The dog is portrayed as an integral part of the natural world, reflecting on its place in both life and death. | Ecocriticism highlights the interconnectedness of all living beings, showing how the dog’s life and death are part of a larger ecological cycle. The poem invites readers to consider the value of non-human lives and their place within the natural world, challenging anthropocentric perspectives. |

| Psychoanalytic Criticism | Analyzes the psychological motivations of characters and their unconscious desires. The poem can be interpreted as a reflection of the owners’ grief and the psychological impact of losing a beloved pet. The dog’s voice may represent the owners’ coping mechanism to deal with loss. | The poem can be seen as an expression of the owners’ unconscious guilt and sorrow, with the dog’s words providing comfort and closure. Through this lens, the poem explores themes of attachment, loss, and the process of mourning, offering insight into the human psyche’s response to death and separation. |

| Human-Animal Studies | Examines the relationships between humans and animals, focusing on how animals are represented in literature. The poem portrays the dog as a sentient being with emotions, memories, and a deep bond with its human companions, challenging traditional human-animal hierarchies. | The poem blurs the line between human and animal by giving the dog a voice and portraying it as an equal companion rather than a subordinate being. This challenges traditional views of animals as lesser creatures and promotes a more empathetic and egalitarian relationship between humans and animals. |

Critical Questions about “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

· Question 1: How does the unique perspective of the poem, narrated from the dog’s point of view, shape the reader’s understanding of the human-animal bond?

- By adopting Haig’s voice, Jeffers innovatively shifts the reader’s focus from a human-centered to an animal-centered perspective. This unconventional choice fosters empathy and challenges anthropocentric assumptions about animals as mere possessions or subordinates. The poem invites readers to consider the depth of emotion and loyalty experienced by a companion animal, enriching their understanding of the complex and reciprocal nature of the human-animal bond.

· Question 2: How does Jeffers explore the contrast between human and canine lifespans, and what does this reveal about the nature of grief?

- Jeffers poignantly juxtaposes the brevity of a dog’s life with the comparatively lengthy human lifespan. This contrast underscores the intensity of grief experienced by the surviving humans, as they confront the finality of their beloved pet’s death. The poem suggests that while grief is a universal human experience, its depth can be magnified by the intensity of the bond and the abruptness of the loss, as in the case of a pet’s death.

· Question 3: How does the domestic setting contribute to the poem’s themes of love, loss, and companionship?

- The intimate domestic setting serves as a microcosm of the human-animal relationship. The familiar spaces described in the poem—the house, the kitchen, the fire—become imbued with the presence of the dog, emphasizing the deep connection between humans and their pets. The loss of this familiar presence within the domestic sphere accentuates the pain of bereavement, while also highlighting the enduring nature of love and companionship.

· Question 4: How does the simplicity of the language contribute to the poem’s overall impact?

- Jeffers’ departure from his typically complex style in “The House Dog’s Grave” serves to amplify the poem’s emotional impact. The straightforward language mirrors the direct and uncomplicated nature of the dog’s perspective, creating a sense of immediacy and authenticity. This simplicity allows the reader to fully engage with the poem’s core themes of love, loss, and loyalty without being distracted by ornate language.

Literary Works Similar to “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

- “The Rainbow Bridge” (Anonymous): A short poem often shared in the context of pet loss, “The Rainbow Bridge” describes a place where pets wait for their owners after death, reflecting themes of love, loss, and reunion similar to those in Jeffers’ poem.

- “A Dog Has Died” by Pablo Neruda: In this poem, Neruda expresses his deep grief and reflection on the life of his beloved dog. Like Jeffers, Neruda gives voice to his pet, acknowledging the bond between human and animal and the pain of loss.

- “To Flush, My Dog” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Browning’s poem is an ode to her cocker spaniel, Flush. It highlights the deep affection and companionship between pet and owner, mirroring the love and devotion evident in Jeffers’ portrayal of the dog’s relationship with its owners.

- “The Power of the Dog” by Rudyard Kipling: This poem explores the deep emotional bond between humans and their dogs, along with the inevitable pain of losing them. Like Jeffers’ work, it reflects on the enduring love and the sorrow that comes with the death of a beloved pet.

- “Elegy on the Death of a Mad Dog” by Oliver Goldsmith: Although Goldsmith’s poem takes a more satirical tone, it deals with the theme of a dog’s death and its impact on humans. It shares with Jeffers’ poem the central focus on the relationship between a dog and its owner, though the treatment of the subject differs.

Suggested Readings: “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

- Brophy, Robert J. Robinson Jeffers: Myth, Ritual, and Symbol in His Narrative Poems. University of Iowa Press, 1976.

- Zaller, Robert. Robinson Jeffers and the American Sublime. Stanford University Press, 2012.

- Boehme, Sarah. The Wild That Attracts Us: New Critical Essays on Robinson Jeffers. University of New Mexico Press, 2015.

Representative Quotations of “The House Dog’s Grave (Haig, an English Bulldog)” by Robinson Jeffers

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “I cannot now / Run with you in the evenings along the shore” | The dog reflects on the loss of shared activities with its owners. | Theme of loss and longing. This line highlights the absence of a cherished companion and the impact of grief on daily routines. |

| “I cannot lie by your fire as I used to do” | The dog reminisces about physical proximity and comfort. | Theme of intimacy and companionship. This quotation emphasizes the closeness and affection between humans and animals, highlighting the loss of physical comfort and emotional connection. |

| “You were never masters, but friends. I was your friend.” | The dog asserts equality in the relationship with humans. | Challenge to anthropocentrism. This line subverts the traditional hierarchical view of humans and animals, suggesting a reciprocal bond based on friendship and mutual respect. |

| “I loved you well, and was loved. Deep love endures / To the end and far past the end.” | The dog expresses the enduring nature of love. | Theme of immortality. This quotation suggests that love transcends physical death, implying a spiritual or emotional continuity beyond the mortal realm. |

| “I hope than when you are lying / Under the ground like me your lives will appear / As good and joyful as mine.” | The dog expresses concern for its owners’ afterlife. | Animal consciousness and empathy. This line raises questions about animal cognition and their capacity to understand human mortality and experience empathy. |