Asian American Literature: Term and Concept

Term

The term “Asian American Literature” refers to the body of literary works produced by authors of Asian descent living in the United States. It encompasses a wide range of genres, including fiction, poetry, non-fiction, drama, and graphic novels. This term highlights the unique experiences, perspectives, and historical contexts that shape the creative expression of Asian American communities.

Concept

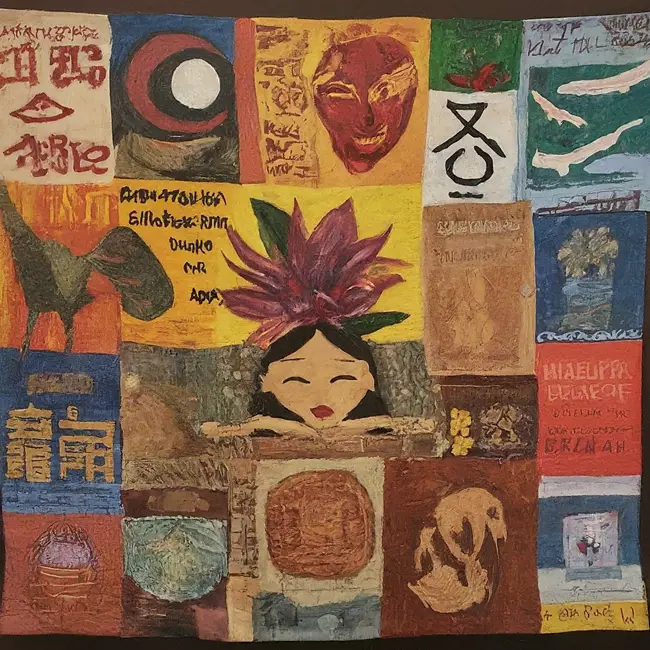

As a broader concept, Asian American Literature explores the multifaceted identities and experiences of people with roots in the vast and diverse continent of Asia living within the American social context. It grapples with themes such as immigration, cultural hybridity, the struggle for belonging, generational conflict, the legacy of colonialism, and the search for an authentic voice within a multicultural society. Asian American Literature often challenges stereotypes, confronts historical injustices, and celebrates the resilience and contributions of Asian American communities.

Asian American Literature: Authors, Works and Arguments

| Author | Key Works | Arguments |

| Maxine Hong Kingston | The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts, China Men | Explores the intersection of Chinese myth, history, and lived experience as a Chinese American woman. Challenges gender roles and questions notions of cultural authenticity. |

| Amy Tan | The Joy Luck Club, The Kitchen God’s Wife | Examines complex mother-daughter relationships, the clash of immigrant and American-born generations, and the enduring power of cultural heritage. |

| Jhumpa Lahiri | Interpreter of Maladies (short stories), The Namesake (novel) | Delves into the experiences of displacement, the search for identity between cultures, and the complexities of family dynamics within the South Asian diaspora. |

| Viet Thanh Nguyen | The Sympathizer, The Refugees | Addresses the legacy of the Vietnam War, the refugee experience, and the multifaceted nature of individual loyalties within conflict. Challenges simplistic representations of war and its consequences. |

| Theresa Hak Kyung Cha | Dictée | Experimental work that blends genres, languages, and visual elements to explore themes of displacement, the fragmentation of memory, and the search for voice as a Korean woman in America. |

| Carlos Bulosan | America is in the Heart | Semi-autobiographical novel depicting the struggles of Filipino migrant workers in America during the 1930s, exposing systemic exploitation and racism. |

| R. Zamora Linmark | Rolling the R’s (poetry) | Explores the experiences of a Filipino American speaker navigating cultural identity, language, and the challenges of belonging in a society marked by prejudice. |

| Chang-Rae Lee | Native Speaker, On Such a Full Sea | Examines themes of assimilation, alienation, and the pursuit of the American Dream as experienced by Korean American characters. Tackles complex issues of race and belonging. |

| Ocean Vuong | On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (poetry) | Explores themes of sexuality, intergenerational trauma, and the complexities of immigrant family dynamics within a Vietnamese American context. Utilizes visceral and lyrical language. |

| Cathy Park Hong | Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning | Blends personal essay and social critique to examine the insidious nature of everyday racism faced by Asian Americans, and the unique emotional landscape it cultivates. |

Asian American Literature: Key Principals

Key Principles

- Heterogeneity and Diversity: Asian American Literature encompasses a vast range of experiences, reflecting diverse ethnicities, national origins, religions, socioeconomic backgrounds, and immigration histories.

- Literary References: Collections like “Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers” and “Charlie Chan is Dead: An Anthology of Contemporary Asian American Fiction” showcase this multiplicity of voices.

- Intergenerational Tensions: A recurring theme is the conflict between immigrant parents and their American-born children, who navigate differing worldviews and cultural expectations.

- Literary References: Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club” and Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake” poignantly explore these complex dynamics.

- The Search for Identity and Belonging: Characters often grapple with questions of cultural hybridity, negotiating their Asian heritage within the dominant American social landscape. Works address internalized racism, experiences of alienation, and the desire for acceptance.

- Literary References: Maxine Hong Kingston’s “The Woman Warrior” and Chang-Rae Lee’s “Native Speaker” delve into these complexities.

- Historical Trauma and its Legacy: Many works address the enduring consequences of historical events such as colonialism, wars, forced displacement, and discrimination.

- Literary References: Viet Thanh Nguyen’s “The Sympathizer” examines the Vietnam War’s aftermath, while Julie Otsuka’s “When the Emperor Was Divine” portrays the Japanese American internment experience.

- Challenging Stereotypes and Reclaiming Narratives: Asian American authors actively dismantle harmful tropes and stereotypes, presenting multifaceted characters and stories that reflect lived experiences with depth and nuance.

- Literary References: Works like R. Zamora Linmark’s poetry or Cathy Park Hong’s “Minor Feelings” confront and dismantle harmful stereotypes.

Important Note: These principles are interconnected and by no means exhaustive. Asian American Literature is a vibrant and evolving field!

Asian American Literature: Relevance to Literary Theories

- Postcolonial Literature and Theory: Asian American Literature often grapples with the legacies of colonialism, both the direct experiences of countries like the Philippines and India, as well as the indirect impact on diaspora communities. Works address issues of power imbalances, cultural erasure, and the search for identity in a postcolonial world. Examples include Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer.

- Critical Race Theory: Asian American Literature foregrounds experiences of race, racism, and the ways in which racialization shapes individual lives and societal structures. It challenges the model minority myth and exposes the lived realities of discrimination and marginalization. Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings directly engages with Critical Race Theory to analyze the specific experiences of Asian Americans.

- Diaspora Studies: Works often explore themes of displacement, longing for homeland, and the process of forging a new sense of belonging in a foreign land. Writers like Jhumpa Lahiri and Ocean Vuong address the complexities of living in-between cultures and the psychological impact of diasporic life

- Intersectionality: Asian American Literature highlights how race, gender, class, sexuality, and other identity markers intersect to shape experiences uniquely. Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior explores these intersections within the context of Chinese American womanhood, while Ocean Vuong’s poetry delves into queer identity within an immigrant family.

- Narrative Theory: Asian American authors often experiment with narrative form, blending oral traditions, non-linear storytelling, and multi-lingualism. This challenges traditional Western narrative structures and offers alternative ways to convey experiences and histories. Maxine Hong Kingston’s work and R. Zamora Linmark’s poetry exemplify this experimentation.

Why this Matters

The relevance of Asian American Literature to literary theory lies in its ability to:

- Expand the Canon: It introduces perspectives and experiences often marginalized within traditional literary studies.

- Challenge Assumptions: It complicates notions of American identity, national narratives, and the power dynamics inherent in literary representation.

- Enrich Analysis: Applying various theoretical frameworks to Asian American texts reveals complexities often overlooked by dominant critical lenses.

Asian American Literature: Key Terms

| Term | Definition |

| Diaspora | The dispersion of Asian communities across the globe, often reflecting experiences of migration. |

| Hybridity | The blending of Asian and American cultures, identities, and experiences. |

| Identity | The complex exploration of belonging, self-definition, and cultural heritage. |

| Racism | Systemic discrimination and prejudice faced by Asian Americans in various contexts. |

| Immigration | Narratives of migration, settlement, and the challenges of adapting to a new country. |

| Assimilation | The process of adopting American customs while retaining cultural roots and identity. |

| Nostalgia | Longing for a homeland, past experiences, or cultural traditions left behind. |

| Cultural Heritage | Celebration and preservation of the richness of Asian traditions, values, and practices. |

| Community | Solidarity, support, and shared experiences among Asian American individuals and groups. |

| Intersectionality | Understanding how race, gender, class, and other identities intersect and shape experiences. |

Asian American Literature: Suggested Readings

- Bulosan, Carlos. America is in the Heart: A Personal History. University of Washington Press, 2014.

- Cha, Theresa Hak Kyung. Dictée. University of California Press, 2001.

- Hong, Cathy Park. Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning. One World, 2020.

- Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts. Vintage, 1976.

- Lahiri, Jhumpa. Interpreter of Maladies. Mariner Books, 1999.

- Lee, Chang-rae. Native Speaker. Riverhead Books, 1995.

- Linmark, R. Zamora. Rolling the R’s. Hanging Loose Press, 1995.

- Nguyen, Viet Thanh. The Sympathizer. Grove Press, 2015.

- Tan, Amy. The Joy Luck Club. Penguin Books, 1989.

- Vuong, Ocean. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: A Novel. Penguin Press, 2019.