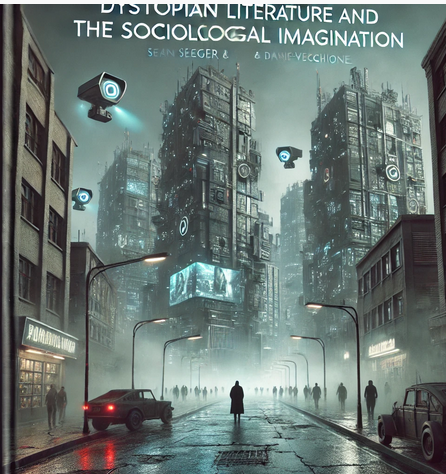

Introduction: “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione

“Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger and Daniel Davison-Vecchione first appeared in Thesis Eleven in 2019. The article argues that sociologists can benefit from a deeper engagement with dystopian literature, as it provides a speculative yet empirically grounded lens on social reality. Unlike utopian literature, which often presents idealized visions of society, dystopian fiction offers a nuanced exploration of the tensions between individual experiences and broader social-historical forces. The authors position dystopian literature as an exercise in what C. Wright Mills famously termed the sociological imagination—the ability to understand the relationship between personal biography and historical-social structures. The article emphasizes how dystopian narratives illuminate the reciprocal shaping of personal identity and societal conditions, making them a valuable analytical tool for sociologists. Drawing on figures like H.G. Wells, Krishan Kumar, Ruth Levitas, and Zygmunt Bauman, the authors argue that dystopian literature is not merely a genre of speculative fiction but a form of sociological thought in its own right. By examining works such as Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Huxley’s Brave New World, and Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, they illustrate how dystopian fiction can reveal and critique dominant social structures, making it an essential component of both literary theory and sociological inquiry. Their analysis challenges the traditional neglect of dystopia in sociological discourse and calls for its recognition as a serious tool for understanding contemporary social and political transformations.

Summary of “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione

1. The Relationship Between Dystopian Literature and Sociology

- The article argues that dystopian literature is a powerful tool for sociological inquiry because it is more grounded in empirical social reality than utopian literature (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 1).

- Dystopian fiction explores the relationship between individuals and the broader social-historical structures, illustrating how external forces shape personal experiences (p. 2).

- The authors link this concept to C. Wright Mills’ notion of the sociological imagination, which enables individuals to understand personal experiences in relation to societal structures (Mills, 2000, p. 6).

2. Speculative Literature as a Sociological Tool

- Social theorists such as Krishan Kumar, Ruth Levitas, and Zygmunt Bauman have acknowledged the role of speculative literature in sociology (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 2).

- H.G. Wells viewed the creation and critique of utopias as central to sociology, arguing that imagination is crucial for understanding social structures (Wells, 1907, p. 367).

- Levitas proposed a utopian method of sociology called the Imaginary Reconstitution of Society (IROS), which involves envisioning alternative social futures (Levitas, 2010, p. 543).

3. The Imbalance Between Utopian and Dystopian Studies in Sociology

- Sociologists have historically focused more on utopian literature than dystopian literature (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 4).

- Dystopian fiction has been largely treated as an “anti-utopian” genre rather than an independent mode of sociological exploration (Kumar, 1987, p. viii).

- The authors argue that dystopian fiction should be analyzed on its own terms because it provides critical insights into social structures and the consequences of contemporary trends (p. 5).

4. Mills’ Concept of the Sociological Imagination and Dystopia

- Mills’ sociological imagination highlights the connection between individual experience (biography) and larger social forces (history) (Mills, 2000, p. 6).

- This concept aligns closely with dystopian fiction, which portrays individuals navigating oppressive social structures and historical transformations (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 6).

- While Mills was ambivalent about the role of fiction in sociology, he acknowledged that literature can illustrate societal transformations, citing Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four as an example (Mills, 2000, p. 171).

5. Bauman’s Engagement with Dystopian Literature

- Zygmunt Bauman explored dystopian themes in works such as Modernity and the Holocaust, Liquid Modernity, and Retrotopia (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 7).

- He linked dystopian fiction to modernity, bureaucracy, and social engineering, viewing Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Huxley’s Brave New World as reflections of specific historical fears (Bauman, 2000a, p. 26).

- Bauman suggested that contemporary dystopias might offer insights into the uncertainties of “liquid modernity,” characterized by instability and rapid social change (Bauman, 2000b, p. 53).

6. The Need for a More Nuanced Understanding of Dystopia

- Dystopia has often been misinterpreted as merely anti-utopia, but the genre is more diverse (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 10).

- Gregory Claeys distinguishes between three types of dystopias: political, environmental, and technological (Claeys, 2017, p. 5).

- The authors argue that dystopian fiction frequently extrapolates from present conditions to illustrate possible future societal trajectories, rather than simply opposing utopian ideals (p. 11).

7. Extrapolative Dystopias and Contemporary Social Critique

- Many dystopian novels extend existing social, political, and technological trends into the near future, functioning as a critique of contemporary issues (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 12).

- Examples of extrapolative dystopias include:

- Dave Eggers’ The Circle – Explores corporate control, surveillance, and the erosion of democracy (Eggers, 2014).

- Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan – Depicts environmental destruction, authoritarian rule, and class division (Yuknavitch, 2017).

- William Gibson’s Neuromancer – Highlights the consequences of corporate dominance and social alienation under capitalism (Gibson, 1984).

- These works emphasize how dystopian fiction reveals structural inequalities and challenges prevailing ideologies.

8. Dystopian Literature as a Bridge Between Subjective and Objective Social Realities

- Unlike utopian fiction, which often presents an outsider’s perspective, dystopian fiction is typically narrated from within the oppressive society (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 15).

- Characters in dystopian novels—such as Orwell’s Winston Smith, Atwood’s June, and Butler’s Lauren Olamina—are embedded in their societies and critically reflect on their social conditions (p. 16).

- This internal perspective allows dystopian literature to illustrate how macro-level social structures shape individual experiences in ways that sociology often struggles to capture (p. 17).

9. Dystopian Fiction as a Tool for Sociological Engagement

- The authors argue that dystopian fiction is an exercise in sociological imagination, helping readers recognize and critique the trajectories of real-world societies (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 18).

- Writers of dystopian fiction often transition into direct social commentary, as seen in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World Revisited, which reflected on the implications of his fictional world in reality (Huxley, 1958).

- By portraying potential social futures, dystopian fiction encourages critical thinking and active engagement with pressing social issues (p. 19).

Conclusion: The Need for Greater Sociological Attention to Dystopia

- The authors call for sociologists to take dystopian fiction more seriously as a source of insight into contemporary and future social conditions (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 19).

- Dystopian literature aligns with key sociological traditions, particularly in German social thought, by emphasizing the historical embeddedness of human experience (p. 19).

- Given its potential to illuminate power structures, systemic inequalities, and social anxieties, dystopian fiction deserves a central place in sociological inquiry.

Theoretical Terms/Concepts in “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione

| Theoretical Term/Concept | Definition/Explanation | Reference in the Article |

| Sociological Imagination | The ability to understand the relationship between individual experiences (biography) and larger social forces (history) (Mills, 2000). | The authors argue that dystopian literature exemplifies this concept by illustrating how social structures shape personal experiences (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 6). |

| Utopia | An ideal or perfect society, often used as a benchmark for evaluating existing social conditions. | Utopian literature has been widely studied in sociology, but dystopian literature has been largely overlooked (p. 4). |

| Anti-Utopia | A critique of utopian ideals, depicting failed utopian projects that result in oppression or disaster. | Often conflated with dystopia, but the authors argue that dystopian literature is a broader category with distinct features (p. 10). |

| Dystopia | A fictional portrayal of a repressive or degraded society, often extrapolated from real-world social, political, or technological trends. | The article argues that dystopian fiction is more grounded in empirical reality than utopian fiction and is a useful tool for sociological analysis (p. 11). |

| Extrapolative Dystopia | A type of dystopian fiction that extends current social trends into the future to critique contemporary issues. | Examples include The Circle (Eggers, 2014) and The Book of Joan (Yuknavitch, 2017), which explore corporate surveillance and environmental collapse, respectively (p. 12). |

| Liquid Modernity | A concept by Zygmunt Bauman describing a contemporary social condition characterized by instability, flexibility, and uncertainty. | The authors suggest that dystopian fiction may provide insights into the uncertainties of liquid modernity (Bauman, 2000a, p. 53). |

| Social Structure | The organized patterns of social relationships and institutions that shape human behavior. | Dystopian fiction often illustrates how rigid or oppressive social structures impact individuals (p. 15). |

| Biography and History | The interplay between personal experiences and broader historical/social forces (Mills, 2000). | Dystopian fiction exemplifies this concept by portraying individual struggles within systemic oppression (p. 6). |

| Totalitarian Dystopia | A dystopian society characterized by absolute government control, often depicting surveillance, propaganda, and loss of individual freedom. | Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is cited as an example (p. 8). |

| Retrotopia | Bauman’s concept describing the shift from utopian hopes for the future to nostalgic idealizations of the past. | The authors suggest that contemporary dystopian fiction reflects anxieties about retrotopian tendencies (Bauman, 2017, p. 8). |

| Critical Dystopia | A subgenre of dystopian fiction that retains a utopian impulse by suggesting resistance or alternative possibilities. | The authors reference Tom Moylan’s (2018) work on critical dystopias, which explore possibilities for social change despite bleak settings (p. 10). |

| Pedagogical Use of Speculative Fiction | The practice of using dystopian literature to teach sociological concepts. | The authors differentiate their argument from pedagogical approaches that use dystopian fiction as a “training ground” for sociology students (p. 6). |

| Phenomenology of Social Being | The study of how individuals experience and interpret their social reality. | Dystopian literature serves as a bridge between personal experience and structural forces, offering a phenomenological richness unmatched by empirical sociology (p. 17). |

| Social Engineering | The attempt to design and control society through technological, bureaucratic, or ideological means. | The authors reference Bauman’s Modernity and the Holocaust, which critiques utopian social engineering projects that led to mass oppression (p. 7). |

Contribution of “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione to Literary Theory/Theories

1. The Sociological Imagination and Literary Studies

- Theory: C. Wright Mills’ Sociological Imagination (2000) applied to literature

- Contribution: The article argues that dystopian literature exemplifies the sociological imagination, bridging personal experiences and broader historical-social forces.

- Reference: “Dystopian fiction is especially attuned to the interplay of ‘biography and history’ described by Mills” (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 6).

2. Utopian and Dystopian Literary Theory

- Theory: Fredric Jameson’s Archaeologies of the Future (2005) and Tom Moylan’s Critical Dystopias (2018)

- Contribution: Challenges the conflation of dystopia with anti-utopia, arguing that dystopian fiction does not merely negate utopia but operates as a distinct speculative mode that can critique and expand sociological thought.

- Reference: “While utopia served to negate the present in order to imagine a better future, retrotopia constitutes a utopian negation of utopia’s negation” (p. 8).

- Critique of Jameson: The article pushes against Jameson’s classification of dystopias as merely anti-utopian by emphasizing how dystopian literature functions independently.

- Reference: “While dystopias have often advanced an anti-utopian agenda, they need not do so” (p. 11).

3. Speculative Fiction as a Form of Social Theory

- Theory: H.G. Wells’ Sociological Utopianism (1907) and Richard Hoggart’s Literary Imagination and the Sociological Imagination (1970)

- Contribution: Positions dystopian fiction as a form of social theorizing that extrapolates from empirical reality to imagine possible futures, functioning as an alternative methodology for understanding society.

- Reference: “Constructing and analysing social worlds that ‘might be’ is itself a potent exercise of the sociological imagination” (p. 5).

- Contrast with Hoggart: Extends Hoggart’s argument that literature reflects social reality by suggesting that dystopian literature actively produces sociological insights rather than merely illustrating them.

- Reference: “At their best, the writer and the social scientist are ‘close to each other’ because the latter’s ‘capacity to find hypotheses is decided by [their] imaginative power’ (Hoggart, 1970: 265).”

4. Literary Realism vs. Speculative Realism

- Theory: Bauman’s Liquid Modernity (2000) and Levitas’ Utopia as Method (2013)

- Contribution: Argues that dystopian fiction surpasses traditional literary realism in its ability to depict social transformation and instability characteristic of modernity.

- Reference: “Compared to those of the utopia, the literary conventions of the dystopia more readily illustrate the relationship between the inner life of the individual and the greater whole of social-historical reality” (p. 11).

- Expands Bauman’s Work: Suggests dystopian fiction captures the uncertainty of liquid modernity in ways sociological analysis cannot.

- Reference: “Bauman observes that people often want to know ‘social and historical reality’ but ‘do not find contemporary literature an adequate means for knowing it’ (Mills, 2000: 17).”

5. Postmodern and Late Capitalist Critique

- Theory: Jameson’s Postmodernism (1991) and Gregory Claeys’ Tripartite Dystopian Model (2017)

- Contribution: Extends postmodern literary theory by demonstrating how dystopian fiction critiques neoliberalism, surveillance, and climate collapse through extrapolative world-building.

- Reference: “Acclaimed recent examples of extrapolative dystopias would include Dave Eggers’ The Circle (2014) and Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan (2017)” (p. 12).

- Engagement with Claeys: Expands Claeys’ tripartite dystopian model (political, environmental, technological) by emphasizing how these dystopias reveal the long-term consequences of existing trends.

- Reference: “Claeys observes that ‘it is the totalitarian political dystopia which is chiefly associated with the failure of utopian aspirations’” (p. 11).

6. Narrative Perspective and the Subjective Experience of Oppression

- Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin’s Dialogism (1981) and Feminist Dystopian Studies (Atwood, Butler)

- Contribution: Highlights how dystopian literature foregrounds subjective experience through its use of first-person or deeply interiorized third-person narration, unlike utopian fiction, which typically employs an external observer’s perspective.

- Reference: “Utopias adhere to a generic convention whereby they adopt the perspective of a visitor or outsider figure … dystopia, by contrast, is almost always described from an inhabitant’s perspective” (p. 15).

- Engagement with Feminist Dystopias: Analyzes The Handmaid’s Tale (Atwood, 1985) and Parable of the Sower (Butler, 1993) as examples of dystopian fiction exploring gender, race, and subjectivity.

- Reference: “Octavia Butler’s Parable series imagines a dystopian America that interrogates the real present in the context of a fictional future” (p. 13).

7. Literature as a Political Intervention

- Theory: Huxley’s Brave New World Revisited (1958) and C. Wright Mills’ Public Sociology

- Contribution: Suggests that dystopian fiction not only critiques but actively shapes public discourse on contemporary social issues.

- Reference: “Nearly 30 years after Brave New World, Huxley published Brave New World Revisited, reflecting on the real-world developments that dystopian fiction had anticipated” (p. 17).

- Public Sociology Angle: Echoes Mills’ belief that sociologists should engage with the public by demonstrating how dystopian fiction fosters awareness and critique of public issues like surveillance and environmental crises.

- Reference: “Dystopian fiction implies that we may be able to intervene to prevent such outcomes” (p. 16).

Conclusion: Expanding the Literary-Sociological Interface

- The article redefines dystopian literature as a sociological and theoretical tool, rather than merely a genre of social critique.

- It challenges dominant literary classifications (e.g., Jameson’s anti-utopia) by showing dystopia’s analytical richness in understanding contemporary society.

- It bridges literary theory and sociology, arguing that dystopian fiction is not just a reflection of society but an active form of theorization and public engagement.

Examples of Critiques Through “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione

| Literary Work | Critique through “Dystopian Literature and the Sociological Imagination” | Key References from the Article |

| Nineteen Eighty-Four (George Orwell) | – Illustrates how dystopian literature engages the sociological imagination by demonstrating the interplay between biography and history. – Orwell’s depiction of totalitarian surveillance and control aligns with the concerns of modern sociology regarding the power structures that shape individual experiences. – Functions as a political dystopia, illustrating how regimes manipulate truth and control social structures. | – “Dystopian fiction is especially attuned to the interplay of ‘biography and history’ described by Mills” (Seeger & Davison-Vecchione, 2019, p. 5). – “Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is listed alongside sociological classics as a work that illustrates the modern ‘advent of the alienated man’” (p. 171-172). |

| Brave New World (Aldous Huxley) | – Demonstrates how technological and psychological control in dystopian societies affect subjectivity and social structures. – Depicts an anti-utopia, revealing the dangers of a society that prioritizes stability and pleasure at the cost of individuality and critical thought. – Highlights how conformity and predictability in a highly regulated society stifle human agency and resistance. | – “Huxley’s Brave New World may be read as an ‘inventory of the fears and apprehensions which haunted modernity during its heavy stage’” (p. 26). – “The foreboding of a tightly controlled world is a recurring theme in dystopian literature” (p. 53). |

| The Handmaid’s Tale (Margaret Atwood) | – Highlights how dystopian fiction bridges the private and the public, showing how personal struggles reflect broader historical changes. – Depicts gender oppression and religious authoritarianism, showcasing how power structures shape individual experiences. – Functions as an extrapolative dystopia, using historical trends to project a possible near-future society. | – “Like Orwell’s Oceania, Gilead originates as a pragmatic response to an unforeseen series of crises, not as an attempt to engineer a perfect society” (p. 12). – “Dystopian fiction helps us envisage the relationship between biography and history” (p. 16). |

| Parable of the Sower (Octavia Butler) | – Serves as an example of an extrapolative dystopia, showing how social collapse, racial inequality, and neoliberal economic policies shape dystopian futures. – Demonstrates how dystopian literature functions as a sociological thought experiment, presenting speculative scenarios based on real-world socio-economic conditions. – Highlights environmental degradation, privatization, and corporate dominance, which are increasingly relevant sociological concerns. | – “Butler’s dystopian America is firmly grounded in empirical reality, extrapolating from existing social and economic trends” (p. 13). – “Like Atwood’s Gilead, Butler’s dystopian America is depicted as a product of longstanding societal failures” (p. 13). |

Criticism Against “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione

1. Overemphasis on Dystopian Literature’s Sociological Utility

- The article argues that dystopian literature serves as a form of sociological imagination, but it does not sufficiently address the limitations of literature as a sociological method.

- While dystopian fiction can provide insights into social structures, it remains a speculative and fictional medium rather than an empirical discipline.

- The authors do not fully engage with potential methodological critiques regarding the lack of rigorous sociological data in literary studies.

2. Neglect of Utopian Literature’s Sociological Value

- The article suggests that dystopian literature is more sociologically relevant than utopian literature, which may be an oversimplification.

- Scholars like Ruth Levitas and Fredric Jameson have argued that utopian literature is crucial for envisioning alternatives to existing social structures, a perspective the authors do not adequately address.

- The dismissal of utopian literature as less grounded in empirical reality overlooks the role of utopian speculation in sociology and political thought.

3. Limited Engagement with Alternative Literary Criticism Approaches

- The article mainly frames dystopian literature through the lens of C. Wright Mills’ sociological imagination, but it does not engage deeply with other critical perspectives, such as:

- Marxist literary criticism, which examines dystopian literature in terms of class struggle and economic systems.

- Postcolonial critiques, which could provide insight into how dystopian narratives engage with themes of imperialism and racial oppression.

- Feminist theory, particularly in analyzing gendered oppression in dystopian literature beyond the examples provided.

4. Overgeneralization of Dystopian Subgenres

- The article collapses various forms of dystopian literature into a singular sociological function, despite the diversity of dystopian texts.

- Gregory Claeys’ distinction between political, environmental, and technological dystopias is mentioned, but the authors do not fully explore how different dystopian texts serve distinct sociological purposes.

- The argument that dystopian fiction is inherently sociologically valuable does not account for works that focus more on aesthetic experimentation or abstract philosophical concerns rather than social critique.

5. Insufficient Discussion of Reader Reception and Interpretation

- The article assumes that dystopian literature inherently fosters a sociological imagination, but it does not consider how different readers interpret these texts.

- Not all readers approach dystopian literature as a sociological tool—some engage with it as entertainment, allegory, or personal reflection.

- The authors could have incorporated reader-response theory to explore how dystopian texts function differently depending on the audience and cultural context.

6. Ambiguity in Defining “Dystopia” vs. “Anti-Utopia”

- The article critiques the conflation of dystopia with anti-utopia but does not provide a clear alternative framework for distinguishing them.

- While the authors push back against Krishan Kumar and Fredric Jameson’s view of dystopia as inherently anti-utopian, their argument remains somewhat vague and lacks a systematic classification of dystopian fiction.

- The claim that dystopian literature is uniquely positioned to illustrate the interplay of biography and history could have been more rigorously defended with specific theoretical backing.

7. Lack of Consideration for Contemporary and Digital Dystopian Narratives

- The article focuses primarily on canonical dystopian literature (Nineteen Eighty-Four, Brave New World, The Handmaid’s Tale), but does not address contemporary forms of dystopian media, such as:

- Dystopian films and television series (e.g., Black Mirror, The Hunger Games, The Man in the High Castle).

- Video games and interactive fiction that explore dystopian themes in immersive ways.

- Online and social media-driven dystopian discourse, which has reshaped public engagement with dystopian concepts.

8. Potentially Elitist View of Literature’s Role in Sociology

- The article implies that dystopian literature provides sociological insights in a way that non-literary cultural forms do not, which may be a literary elitist stance.

- Other speculative media, including music, visual art, and internet culture, have also contributed significantly to sociological discourse but are not considered in the article.

- The exclusive focus on literature may reinforce traditional academic hierarchies that prioritize text-based analysis over interdisciplinary cultural studies.

Representative Quotations from “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione with Explanation

.

| Quotation | Explanation |

| “Dystopian literature is especially attuned to how historically-conditioned social forces shape the inner life and personal experience of the individual, and how acts of individuals can, in turn, shape the social structures in which they are situated.” | This highlights the core argument of the paper: dystopian literature functions as an exercise in sociological imagination, illustrating the interplay between individuals and social structures. |

| “The speculation in dystopian literature tends to be more grounded in empirical social reality than in the case of utopian literature.” | The authors contrast dystopian and utopian literature, arguing that dystopian fiction is more closely tied to real-world societal trends, making it more valuable for sociological analysis. |

| “While utopia served to negate the present in order to imagine a better future, retrotopia constitutes what Bauman calls a ‘negation of utopia’s negation’ – a utopian negation of utopia’s negation of the present in order to imagine a better past.” | This refers to Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of retrotopia, in which societies long for an idealized past rather than working towards a progressive future, reflecting a shift in the sociopolitical landscape. |

| “Not all dystopian literature is intended to convey a warning about the limits of utopian planning or the hubris of promethean projects of world transformation.” | The authors challenge the dominant notion that dystopian literature is inherently anti-utopian, suggesting that dystopias have a broader range of social critiques beyond failed utopianism. |

| “Bauman describes Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four as an ‘inventory of the fears and apprehensions which haunted modernity during its heavy stage.’” | The reference to Bauman indicates how Orwell’s work encapsulated fears of totalitarianism and social control in the context of industrial modernity, a theme that remains relevant. |

| “Dystopian fiction is notably adept at drawing the connections between private troubles and public issues that Mills considered fundamental to sociological thinking.” | This reinforces the argument that dystopian fiction exemplifies C. Wright Mills’ sociological imagination by showing how personal experiences are shaped by larger social forces. |

| “One could therefore view dystopian fiction as a bridge between the phenomenology and the historicity of social being.” | The authors suggest that dystopian literature functions as an intersection between subjective experience and historical social structures, making it a useful tool for sociological inquiry. |

| “Where dystopia is addressed, it is generally by way of contrast with utopia in order to bring the outline of the latter more clearly into view, rather than as a distinct topic meriting sociological consideration in its own right.” | The authors critique the neglect of dystopian literature in sociology, arguing that it deserves independent scholarly attention rather than being treated merely as an inverse of utopian studies. |

| “Extrapolative dystopias work by identifying something already taking place in society and then employing the resources of imaginative literature to extrapolate to some conceivable, though not inevitable, future state of affairs.” | This emphasizes how dystopian literature projects possible futures by extending real-world trends, making it a valuable speculative tool for sociologists. |

| “Dystopian fiction helps people envisage the relationship between biography and history.” | The authors reaffirm the argument that dystopian literature enables readers to understand how historical and societal forces shape individual lives, aligning with Mills’ concept of sociological imagination. |

Suggested Readings: “Dystopian Literature And The Sociological Imagination” by Sean Seeger And Daniel Davison-Vecchione

- Seeger, Sean, and Daniel Davison-Vecchione. “Dystopian literature and the sociological imagination.” Thesis Eleven 155.1 (2019): 45-63.

- Allen, Danielle. “On the Sociological Imagination.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 30, no. 2, 2004, pp. 340–41. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/421129. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025

- Hironimus-Wendt, Robert J., and Lora Ebert Wallace. “The Sociological Imagination and Social Responsibility.” Teaching Sociology, vol. 37, no. 1, 2009, pp. 76–88. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20491291. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.

- Rose, Arnold M. “Varieties of Sociological Imagination.” American Sociological Review, vol. 34, no. 5, 1969, pp. 623–30. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2092299. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.

- Noble, Trevor. “Sociology and Literature.” The British Journal of Sociology, vol. 27, no. 2, 1976, pp. 211–24. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/590028. Accessed 4 Mar. 2025.