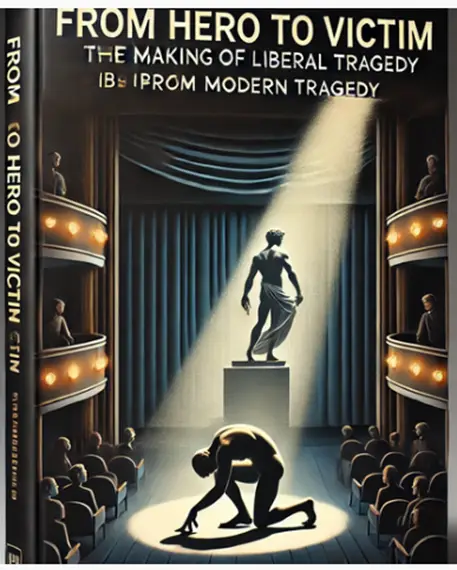

Introduction: “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams

“From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy” by Raymond Williams is a pivotal chapter in his groundbreaking work, Modern Tragedy, published in 1966. This essay has significantly impacted literary and literary theory discourse, particularly in its exploration of the evolution of tragic figures from heroic protagonists to vulnerable victims in modern drama. Williams delves into the works of Henrik Ibsen and Arthur Miller, analyzing how these playwrights redefined the tragic hero in response to the changing social and cultural landscape of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Summary of “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams

- Liberal Tragedy’s Structure and Decline

Liberal tragedy centers around a man who, at the peak of his powers, confronts forces that ultimately defeat him. This tension between individual aspirations and inevitable defeat defines liberal tragedy. Williams notes that while this structure governed for centuries, its ability to hold is now weakening (Williams, 114). - Greek Tragedy and the Shift in Interpretation

Williams argues that modern interpretations of Greek tragedy erroneously emphasize individual psychology, when the original focus was on broader historical and cosmic forces. In Greek tragedy, the hero’s fate was tied to the mutability of the world, not personal flaws (Williams, 114–115). This shift in understanding is a consequence of the modern liberal structure of feeling, which now is in decline. - Renaissance and the Emergence of Individualism in Tragedy

The Renaissance introduced a humanist spirit into tragedy, with individual destiny and personal energy becoming the focal points. The transition from the medieval morality play to Elizabethan tragedy marked a shift where individual experience became central. Tragedy began to focus on the intense, personal exploration of life’s limits (Williams, 115–116). - Public Order and Personal Tragedy

Despite the emphasis on the individual, tragedy during the Elizabethan era often still linked personal experiences to broader social orders, with heroes like princes embodying public concerns. The tension between individual personality and social role was a source of tragedy during this period (Williams, 116–117). - Bourgeois Tragedy and the Rise of Pity

By the 18th century, tragedy adapted to middle-class concerns, focusing on “private woe” and “pity.” However, this shift resulted in a loss of dimension, with personal sympathy replacing broader societal critiques (Williams, 118–119). The emphasis on private sympathy neglected the social realities of power and property, diminishing the societal impact of tragedy. - Transition to Modern Tragedy: From Hero to Victim

Williams notes a shift from heroic figures confronting societal structures to individuals becoming victims of these very structures. In bourgeois tragedy, property and social order replaced the heroic struggles of earlier tragedies, with the hero reduced to a victim of societal contradictions (Williams, 119–120). - Ibsen’s Liberal Tragedy: Individualism and Social Critique

Ibsen’s plays often feature individuals confronting a false society. His characters’ struggles for self-fulfillment are both necessary and tragic. Williams explains that Ibsen’s heroes, like Brand and Stockmann, fight for personal wholeness in the face of societal lies, yet are often destroyed by their own struggle (Williams, 121–123). Ibsen encapsulates the essence of liberal tragedy, where individuals, in their quest for fulfillment, encounter inevitable defeat. - Miller’s Tragic Victims: Society’s Commodification of Individuals

In the works of Arthur Miller, particularly Death of a Salesman and The Crucible, the transition from heroic individuals to victims is fully realized. Characters like Willy Loman represent individuals commodified by society, whose aspirations only lead to their destruction. Miller’s protagonists are no longer liberators but victims trapped by the very society they sought to navigate (Williams, 130–132). - The Collapse of Liberal Tragedy

Williams concludes that liberal tragedy eventually breaks down as individuals turn against themselves. This shift marks the end of the heroic phase and the rise of a victimized, self-enclosed consciousness. Miller’s tragedies, such as Death of a Salesman, illustrate this self-enclosure, with the individual’s desire ultimately leading to self-destruction (Williams, 127–128).

Literary Terms/Concepts in “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams

| Literary Term/Concept | Explanation | Reference/Explanation in the Text |

| Liberal Tragedy | A form of tragedy centered around the individual’s struggle for self-fulfillment in a false society. | The individual seeks to break free but is often destroyed in the process, as seen in Ibsen and Miller. |

| Tragic Hero | A character of noble stature whose downfall is caused by a combination of personal flaw and fate. | The classical tragic hero transforms into a victim in modern tragedy, from aspiration to defeat (Williams, 114). |

| Humanism | Emphasis on individual human potential and agency, often in conflict with societal forces. | Seen in Renaissance tragedies where individual destiny became central, especially in works by Shakespeare (Williams, 115). |

| Pity and Sympathy | Emotional responses to the suffering of characters, particularly in bourgeois tragedy. | The shift from noble tragedy to “private woe” in middle-class tragedy, emphasizing personal distress (Williams, 118). |

| Bourgeois Tragedy | Tragedy that centers around middle-class protagonists and focuses on personal, rather than societal, struggles. | Emerging in the 18th century, it focused on private sympathy, but lost the broader societal dimensions of earlier tragedies (Williams, 118-119). |

| Heroic Individualism | The notion of a lone individual challenging society or cosmic forces, characteristic of liberal tragedy. | Characters in Ibsen, like Brand, fight for personal wholeness against a false society, though often at personal cost (Williams, 121). |

| Alienation | A theme where characters feel estranged or disconnected from society or themselves. | In Ibsen’s and Miller’s works, characters often confront societal structures that alienate them from fulfillment (Williams, 121–123, 130). |

| Romantic Tragedy | A form of tragedy focused on intense individual desire and rebellion against societal conventions. | Romantic figures like Faust and Prometheus embody this intense, rebellious individualism, often with tragic consequences (Williams, 120). |

| Commodification | The transformation of individuals into commodities or objects for economic gain, particularly in modern society. | Seen in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, where Willy Loman becomes commodified by the capitalist society (Williams, 130). |

| Victimization | The transition from heroic figures to tragic victims in modern tragedy, as societal forces become more oppressive. | Williams describes this shift from the hero to the victim, especially in Miller’s tragedies where characters like Willy Loman are destroyed by societal norms (Williams, 127, 131). |

| False Society | A corrupt or flawed society that restricts individual fulfillment and is a central antagonist in liberal tragedy. | Ibsen’s plays repeatedly depict a false, oppressive society, leading to the tragic destruction of the individual (Williams, 122). |

| Tragic Consciousness | The realization that personal desire leads to inevitable defeat within a false society. | Characters in Ibsen and Miller experience this tragic awareness of their entrapment by society and self (Williams, 128). |

| Existential Tragedy | Tragedy rooted in the existential struggles of individuals confronting a meaningless or indifferent universe. | Found in Ibsen and later existentialist drama, where individuals confront personal limits and societal constraints (Williams, 127). |

Contribution of “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams to Literary Theory/Theories

- Development of Tragedy Theory: From Aristotelian to Modern Perspectives

Williams offers a re-evaluation of classical tragedy, particularly the Aristotelian model of the tragic hero with a fatal flaw, by challenging its application to Greek tragedy. He emphasizes that Greek tragedy is historically grounded, not psychologically driven, contributing to a broader historical-materialist understanding of tragedy.

“It is now becoming clear… that the Greek tragic action was not rooted in individuals, or in individual psychology, in any of our senses. It was rooted in history, and not a human history alone” (Williams, 114). - Humanism and Individualism in Renaissance Tragedy

Williams explores how Renaissance tragedy evolved to emphasize individualism and humanism, moving away from collective or cosmic forces seen in earlier tragedies. This shift laid the foundation for humanist literary theories that emphasize the individual’s agency, identity, and role in society.

“By the time of Marlowe and Shakespeare, the structure we now know was being actively shaped: an individual man, from his own aspirations, from his own nature, set out on an action that led him to tragedy” (Williams, 115). - Bourgeois Tragedy and Socioeconomic Critique

Williams’ exploration of bourgeois tragedy, where middle-class characters experience private woe, contributes to Marxist literary theory by examining how socioeconomic class structures influence the form and content of tragedy. The rise of “private” tragedy reflects the transition from feudal to capitalist society, focusing on personal distress while concealing deeper social contradictions.

“Bourgeois tragedy… expresses sympathy and pity between private persons, but tacitly excludes any positive conception of society, and thence any clear view of order or justice” (Williams, 119). - Alienation and Modern Tragedy: Contribution to Marxist and Existentialist Theories

Williams’ discussion of alienation, particularly in the works of Ibsen and Miller, ties into both Marxist theories of alienation and existentialist literary theory. He highlights how characters in modern liberal tragedy experience estrangement from society and from themselves, reflecting the breakdown of individual fulfillment in the face of capitalist or bureaucratic systems.

“The tragic voice, of our own immediate tradition, is then first heard: the aspiration for a meaning, at the very limits of a man’s strength… broken down, by contradictory experience” (Williams, 116). - Critique of Liberal Individualism: From Hero to Victim

Williams contributes to the critique of liberalism in literary theory by tracing the transformation of the tragic hero into a tragic victim. In his analysis, the shift from the individual as a heroic figure to one who is victimized by society reflects the limitations of liberal individualism and anticipates the emergence of a more collective or social consciousness in tragedy.

“Liberal tragedy, at its full development, drew from all the sources that have been named, but in a new form and pressure created a new and specific structure of feeling” (Williams, 121). - Psychological Guilt and Breakdown in Modern Tragedy

The internalization of guilt in modern liberal tragedy, where characters like Ibsen’s and Miller’s are destroyed not just by external forces but by their own internal contradictions, reflects psychoanalytic literary theory. Williams shows how modern tragedy explores the self against the self, contributing to theories of subjectivity and the unconscious in literature.

“The conviction of guilt, and of necessary retribution, is as strong as ever it was when imposed by an external design” (Williams, 127). - Marxism Literary TheoryTransformation of Marxist Criticism in Drama

Williams’ analysis of tragedy integrates Marxist criticism with an understanding of drama as a reflection of the socioeconomic structures that shape personal experiences. By focusing on the transition from feudal to bourgeois to liberal society in the evolution of tragedy, Williams provides a historical-materialist framework for analyzing dramatic forms.

“Rank, that is to say, became class, and once it did so a new definition of tragedy was inevitable” (Williams, 119).

Examples of Critiques Through “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams

1. Shakespeare’s Hamlet

- Critique Through Williams’ Concept of Liberal Tragedy and Humanism

Using Williams’ theory, Hamlet can be critiqued as a pivotal example of Renaissance humanist tragedy, where the individual’s internal struggle is foregrounded. Hamlet’s existential dilemma reflects the transition from a medieval worldview to a humanist emphasis on personal agency. The tragic hero is caught between personal aspiration and an overwhelming external world of duty, inheritance, and corruption.- Williams notes that in Renaissance tragedy, “an individual man, from his own aspirations, from his own nature, set out on an action that led him to tragedy” (Williams, 115). Hamlet exemplifies this, as his indecision and internal conflict drive him toward his tragic end.

- Internalization of Conflict

Hamlet’s inner turmoil, where his personal desires conflict with external duties and the expectations of society, aligns with Williams’ understanding of the liberal tragic hero. Hamlet’s inability to reconcile these forces leads to a psychological breakdown, a key feature in Williams’ model of the liberal tragedy.- “The emphasis, as we take the full weight, is not on the naming of limits, but on their intense and confused discovery and exploration” (Williams, 116).

2. Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman

- Critique Through Williams’ Concept of Bourgeois Tragedy and Victimization

Death of a Salesman can be critiqued as a modern liberal tragedy where Willy Loman embodies the transition from hero to victim. In line with Williams’ critique of bourgeois tragedy, Loman is a product of capitalist commodification. He does not fight against societal structures but is victimized by them, becoming a tragic figure within a system that discards him.- “Willy Loman is a man who from selling things has passed to selling himself, and has become, in effect, a commodity which like other commodities will at a certain point be discarded by the laws of the economy” (Williams, 130).

- Tragedy of Alienation

Miller’s tragedy, in Williams’ terms, highlights the alienation of the individual in a capitalist society, where personal aspiration leads to destruction rather than fulfillment. Willy Loman’s downfall is not the result of heroic rebellion but of living the societal lie, which Williams critiques as the hallmark of modern liberal tragedy.- “He brings tragedy down on himself, not by opposing the lie, but by living it” (Williams, 131).

3. Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House

- Critique Through Williams’ Concept of False Society and Individual Liberation

Using Williams’ theory, A Doll’s House can be critiqued as an example of liberal tragedy that highlights the individual’s struggle against a false society. Nora’s journey of self-realization and rejection of societal norms mirrors Williams’ analysis of Ibsen’s liberal tragedies, where the individual fights for self-fulfillment within a corrupt and oppressive social structure.- “Ibsen creates again and again in his plays, with an extraordinary richness of detail, false relationships, a false society, a false condition of man” (Williams, 122).

- Tragic Victimization and Aspiration for Freedom

Nora’s departure at the end of the play represents the liberal ideal of self-fulfillment, but it also signifies the beginning of a tragic journey where the individual’s aspiration for freedom is at odds with societal constraints. Williams’ theory suggests that Nora, like other Ibsen heroes, becomes both a potential liberator and a tragic figure due to the false society she fights against.- “The individual’s struggle is seen as both necessary and tragic. The attempt at fulfillment ends again and again in tragedy: the individual is destroyed in his attempt to climb out of his partial world” (Williams, 123).

4. Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex

- Critique Through Williams’ Reinterpretation of Greek Tragedy

Williams critiques modern readings of Greek tragedy, such as Oedipus Rex, for projecting liberal individualism onto characters like Oedipus, who were originally not defined by individual psychology but by their place within a broader historical and cosmic framework. Instead of focusing on Oedipus’ tragic flaw, Williams would argue that his downfall represents the inevitable clash between human life and the broader, impersonal forces of fate and history.- “The Greek tragic action was not rooted in individuals, or in individual psychology… What we then see is a general action specified, not an individual action generalized” (Williams, 114).

- Tragedy Rooted in History and Fate

According to Williams, Oedipus’ downfall should be understood not as a personal failing but as a reflection of a world order beyond the individual’s control. This contrasts with modern liberal interpretations, which emphasize personal tragedy over historical forces.- “It was rooted in history, and not a human history alone. Its thrust came, not from the personality of an individual but from a man’s inheritance and relationships, within a world that ultimately transcended him” (Williams, 114).

Criticism Against “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams

- Overemphasis on Historical Determinism

Critics might argue that Williams’ analysis places too much emphasis on historical and material forces in shaping the evolution of tragedy, downplaying the role of individual agency and creativity. His historical materialism might be seen as reductive, limiting the complexity of individual expression within literary works. - Neglect of Psychological Depth in Tragedy

Williams critiques the modern focus on individual psychology in tragedy, particularly in the context of Greek tragedy. However, this may overlook the richness of psychological exploration in modern tragedy, particularly in the works of Ibsen and Miller, where internal conflicts and personal flaws are integral to the narrative. - Simplification of Greek Tragedy

Williams challenges the modern interpretation of Greek tragedy as focused on individual flaws, arguing instead that these works are grounded in historical forces. Some critics may find this perspective overly simplistic, as it downplays the complexities of character development and the nuanced exploration of human agency found in Greek tragedies like Oedipus Rex. - Broad Generalizations about the Development of Tragedy

Williams’ narrative of the evolution of tragedy from classical to modern times might be seen as too generalized. By attempting to trace a single line of development from the heroic individual to the modern victim, he may oversimplify the diversity of tragic forms and themes across different cultures and historical periods. - Undervaluing Aesthetic and Formal Qualities

Williams’ focus on the social and ideological functions of tragedy may lead to a neglect of the aesthetic and formal qualities of the works he discusses. His analysis tends to prioritize the historical and political dimensions of tragedy, potentially overlooking the importance of style, language, and dramatic structure in shaping the tragic experience. - Limited Engagement with Non-Western Tragic Traditions

Williams’ discussion of tragedy is largely Eurocentric, focusing on the development of tragedy within Western literary traditions. Critics might argue that his analysis fails to account for the diversity of tragic forms in non-Western cultures, limiting the scope of his study to a specific cultural context. - Overgeneralization in Defining Liberal Tragedy

Some critics might find Williams’ concept of “liberal tragedy” too broad and unspecific, encompassing a wide range of works and authors without sufficiently distinguishing between them. His attempt to define a singular “liberal tragedy” may blur important differences between individual authors’ approaches to tragedy, such as between Ibsen and Miller. - Underrepresentation of Feminist and Gender Perspectives

Williams’ analysis focuses heavily on male tragic figures and lacks engagement with feminist critiques of tragedy or the role of women in tragic literature. His exploration of the “hero” and “victim” does not sufficiently account for how gender shapes tragic roles and experiences in both classical and modern tragedies.

Representative Quotations from “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams with Explanation

| Quotation | Explanation |

| “At the centre of liberal tragedy is a single situation: that of a man at the height of his powers and the limits of his strength, at once aspiring and being defeated, releasing and destroyed by his own energies.” | This defines the essence of liberal tragedy according to Williams: a tension between individual aspiration and inevitable defeat. It encapsulates the transition from heroism to victimhood in modern tragedy. |

| “We have tried to take psychology, because that is our science, into the heart of an action to which it can never, critically, be relevant.” | Williams critiques the modern emphasis on psychological analysis in Greek tragedy, arguing that it misrepresents the historical and collective dimensions of these ancient works. He challenges modern readings that focus on individual flaws. |

| “The action, confidently, takes Everyman forward to the edge of that dark room in which he must disappear… God himself is waiting for Everyman to come.” | This quotation contrasts medieval morality plays like Everyman with Renaissance tragedies, showing how the focus shifted from religious fatalism and divine order to individual experience and human agency. |

| “The tragic voice, of our own immediate tradition, is then first heard: the aspiration for a meaning, at the very limits of a man’s strength.” | Williams refers to the emergence of the “tragic voice” in Renaissance drama, where individuals seek meaning at the edge of their abilities. This marks a shift toward personal struggle in the tragic form. |

| “Bourgeois tragedy… expresses sympathy and pity between private persons, but tacitly excludes any positive conception of society, and thence any clear view of order or justice.” | Williams critiques bourgeois tragedy for its narrow focus on private emotion (pity and sympathy) while neglecting broader societal structures. This represents a key transformation from earlier, socially expansive tragedies. |

| “The most important persistence, for the subsequent history of drama, was that of a public order, at the centre of what is otherwise personal tragedy.” | This highlights how even as tragedy evolved to focus on individual characters, public order and societal concerns remained central, showing the continued tension between personal desires and larger social forces. |

| “Liberal tragedy, at its full development, drew from all the sources that have been named, but in a new form and pressure created a new and specific structure of feeling.” | Williams identifies “liberal tragedy” as a unique amalgamation of humanist, bourgeois, and romantic elements, creating a distinct emotional structure that defines much of modern tragedy. |

| “The individual’s struggle is seen as both necessary and tragic. The evasion of fulfilment, by compromise, breeds false relationships and a sick society.” | Williams argues that in liberal tragedy, the individual’s quest for fulfillment is doomed to failure, as societal compromise corrupts personal relationships and leads to a diseased social environment, as seen in Ibsen’s works. |

| “Willy Loman is a man who from selling things has passed to selling himself, and has become, in effect, a commodity which like other commodities will at a certain point be discarded.” | In Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman’s commodification reflects the dehumanizing effects of capitalism. Williams critiques how the modern individual is reduced to a commodity, a key theme in the evolution of liberal tragedy. |

| “The conflict is then indeed internal: a desire for relationship when all that is known of relationship is restricting; desire narrowing to an image in the mind, until it is realised that the search for warmth and light has ended in cold and darkness.” | This reflects the internal conflicts faced by characters in modern tragedy, particularly in Ibsen’s works, where the quest for fulfillment leads to isolation and existential despair. The internal collapse of the individual is a key theme in liberal tragedy. |

Suggested Readings: “From Hero to Victim: The Making of Liberal Tragedy, to Ibsen and Miller from Modern Tragedy” by Raymond Williams

- Eagleton, Terry. Sweet Violence: The Idea of the Tragic. Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

- Williams, Raymond. Modern Tragedy. Chatto & Windus, 1966.

- Steiner, George. The Death of Tragedy. Yale University Press, 1996.

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300069167/the-death-of-tragedy - Barker, Howard. Arguments for a Theatre. Manchester University Press, 1989.

- Segal, Charles. Tragedy and Civilization: An Interpretation of Sophocles. Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Kott, Jan. The Eating of the Gods: An Interpretation of Greek Tragedy. Northwestern University Press, 1987.

- Elsom, John. Post-War British Theatre Criticism. Routledge, 2013.