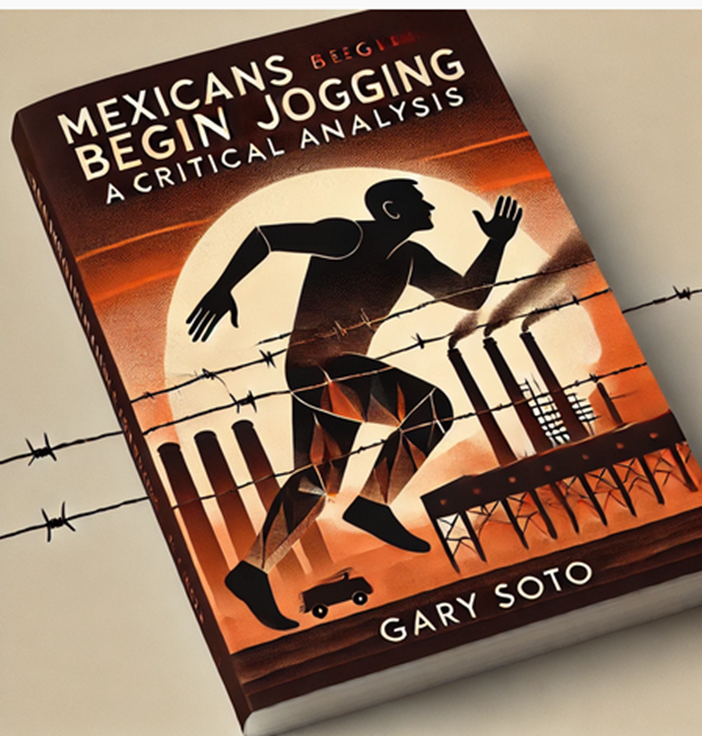

Introduction: “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

“Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto first appeared in 1978 in the collection The Tale of Sunlight, which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. The poem explores themes of racial identity, societal prejudice, and the struggle for acceptance, drawing from Soto’s own experiences as a Mexican-American. It portrays a factory worker, presumably Soto, who is forced to flee from border patrol despite being an American citizen, highlighting the irony and absurdity of racial stereotyping. The speaker’s declaration, “I shouted that I was American,” and the boss’s dismissive response, “No time for lies,” underscore the conflict of being caught between two cultural identities—Mexican by heritage, American by birth. The poem’s popularity stems from its vivid imagery, such as “the fleck of rubber, under the press / Of an oven yellow with flame,” and its ironic tone, exemplified by the speaker’s joyful “vivas / To baseball, milkshakes, and those sociologists,” which transforms a moment of fear into a defiant embrace of American culture. Its accessibility, emotional resonance, and critique of social injustices make it a powerful reflection of the Chicano experience, resonating with readers who relate to the challenges of navigating dual identities in a prejudiced society.

Text: “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

At the factory I worked

In the fleck of rubber, under the press

Of an oven yellow with flame,

Until the border patrol opened

Their vans and my boss waved for us to run.

“Over the fence, Soto,” he shouted,

and I shouted that I was American.

“No time for lies,” he said, and pressed

A dollar in my palm, hurrying me

Through the back door.

Since I was on his time,

I ran And became the wag to a short tail of

Mexicans –

Ran past the amazed crowds that lined

The street and blurred like photographs, in rain

I ram from that industrial road to the soft

Houses where people paled at the turn of an autumn sky.

What could I do but yell vivas

To baseball, milkshakes, and those sociologists

Who would clock me

As I jog into the next century

On the power of a great, silly grin.

Annotations: “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

| Line | Text | Simple Explanation | Detailed Explanation | Literary Devices |

| 1 | At the factory I worked | The speaker says they were working at a factory. | The poem opens by establishing the setting in an industrial workplace, grounding the narrative in the speaker’s labor-intensive environment, likely reflecting Soto’s own Mexican-American experience. | Setting 🏭 |

| 2 | In the fleck of rubber, under the press | Describes working with rubber under a machine. | “Fleck of rubber” highlights the gritty details of manual labor, while “under the press” suggests both physical machinery and societal oppression. | Imagery, Metaphor ⚙️ |

| 3 | Of an oven yellow with flame, | The factory has a hot, glowing yellow oven. | Vivid imagery of a “yellow” oven evokes heat and danger, possibly symbolizing harsh working conditions and societal scrutiny faced by the speaker. | Imagery, Symbolism 🔥 |

| 4 | Until the border patrol opened | Border patrol arrives, creating tension. | The sudden arrival of border patrol shifts the tone to urgency, introducing themes of racial profiling and fear of authority. | Foreshadowing 🚨 |

| 5 | Their vans and my boss waved for us to run. | The boss signals everyone to flee. | The boss’s gesture to “run” shows complicity in assuming the workers are undocumented, revealing systemic fear and workplace dynamics. | Narrative progression 🏃 |

| 6 | “Over the fence, Soto,” he shouted, | The boss yells at Soto to jump a fence. | Naming the speaker “Soto” personalizes the narrative, likely referencing the poet, while the command underscores urgency and dehumanization. | Dialogue, Allusion 🗣️ |

| 7 | and I shouted that I was American. | The speaker protests they are a U.S. citizen. | The speaker’s assertion of American identity, ignored by the boss, highlights the injustice of racial assumptions and erasure of citizenship. | Irony, Conflict 🇺🇸 |

| 8 | “No time for lies,” he said, and pressed | The boss dismisses the claim and urges haste. | The boss’s rejection of the speaker’s truth as a “lie” reflects prejudice, assuming Mexican heritage negates American identity. | Irony, Dialogue 🚫 |

| 9 | A dollar in my palm, hurrying me | The boss gives a dollar and pushes escape. | The “dollar” symbolizes a token gesture or bribe, emphasizing exploitation and the absurdity of the situation. | Symbolism 💵 |

| 10 | Through the back door. | The speaker is rushed out a back exit. | The “back door” represents a secretive, degrading escape, contrasting with the speaker’s rightful claim to belong. | Symbolism 🚪 |

| 11 | Since I was on his time, | The speaker runs under the boss’s orders. | “His time” suggests the speaker’s lack of agency, bound by the boss’s authority, reflecting broader labor and societal control. | Metaphor ⏰ |

| 12 | I ran And became the wag to a short tail of Mexicans – | The speaker leads a group of Mexican workers. | The metaphor “wag to a short tail” likens the speaker to a dog leading others, suggesting both leadership and dehumanization. | Metaphor, Imagery 🐕 |

| 13 | Ran past the amazed crowds that lined | The speaker passes surprised onlookers. | The “amazed crowds” frame the flight as a spectacle, highlighting public scrutiny and the speaker’s alienation. | Imagery 👀 |

| 14 | The street and blurred like photographs, in rain | The scene blurs as the speaker runs. | The simile “blurred like photographs, in rain” creates a chaotic, dreamlike image, suggesting disorientation and fleeting moments. | Simile, Imagery 🌧️ |

| 15 | I ran from that industrial road to the soft | The speaker moves to a residential area. | The contrast between “industrial road” and “soft houses” highlights social divides, moving from gritty to affluent settings. | Juxtaposition 🏠 |

| 16 | Houses where people paled at the turn of an autumn sky. | Residents look shocked under the autumn sky. | “Paled” suggests fear or surprise, while “autumn sky” adds a melancholic tone, symbolizing change or transience. | Imagery, Symbolism 🍂 |

| 17 | What could I do but yell vivas | The speaker shouts cheers defiantly. | The rhetorical question and “vivas” show defiance, reclaiming joy and cultural pride in a moment of fear. | Rhetorical question, Tone 🎉 |

| 18 | To baseball, milkshakes, and those sociologists | The speaker celebrates American culture. | References to “baseball” and “milkshakes” embrace American symbols, while “sociologists” mocks academic categorization. | Irony, Allusion ⚾🥤 |

| 19 | Who would clock me | Sociologists are imagined timing the speaker. | “Clock me” implies scrutiny or measurement, suggesting society’s attempt to define or limit the speaker’s identity. | Metaphor ⏱️ |

| 20 | As I jog into the next century | The speaker imagines running into the future. | “Jog into the next century” symbolizes hope and resilience, with “jog” contrasting the earlier frantic “ran.” | Metaphor, Symbolism 🕰️ |

| 21 | On the power of a great, silly grin. | The speaker runs with a bold smile. | The “great, silly grin” conveys defiance and joy, transforming oppression into personal triumph and optimism. | Imagery, Tone 😄 |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

| Device | Example | Explanation |

| Allusion | “Those sociologists / Who would clock me” | Refers to academics who study identity, migration, or labor—hinting at how Mexicans are often reduced to research subjects. |

| Anaphora | “I ran… / Ran past the amazed crowds” | The repetition of “ran” emphasizes urgency, fear, and the forced movement of the speaker. |

| Assonance | “Over the fence, Soto” | The long “o” vowel sound in “over,” “Soto,” and “no” creates musicality and highlights the moment of escape. |

| Caesura | “Since I was on his time, / I ran” | The pause after the comma breaks the rhythm, mirroring the sudden shift from work to flight. |

| Colloquialism | “No time for lies” | Informal speech reflects working-class dialogue and makes the boss’s command sound immediate and harsh. |

| Contrast | “I shouted that I was American. / ‘No time for lies,’ he said” | Juxtaposes the speaker’s truth with the boss’s disbelief, exposing racial prejudice and stereotypes. |

| Enjambment | “I ran / And became the wag to a short tail of / Mexicans –” | The line break without punctuation mimics continuous running, showing breathless momentum. |

| Hyperbole | “Jog into the next century” | Exaggerates his running as endless, symbolizing how the immigrant struggle stretches across generations. |

| Imagery (Visual) | “The border patrol opened / Their vans” | Creates a vivid image of looming authority and fear. |

| Imagery (Sensory) | “Blurred like photographs, in rain” | Appeals to sight and memory, showing the confusion and speed of the moment. |

| Irony | “I shouted that I was American” | It is ironic that a true American citizen must run from border patrol due to appearance and stereotypes. |

| Metaphor | “Became the wag to a short tail of / Mexicans” | Compares himself to a dog’s wagging tail, showing forced belonging to a group despite his citizenship. |

| Motif | “Run / Jog” repeated throughout | The recurring idea of running symbolizes survival, displacement, and identity crisis. |

| Paradox | “On the power of a great, silly grin” | The grin is “silly,” yet it empowers him to resist despair—holding both weakness and strength. |

| Personification | “Soft houses where people paled at the turn of an autumn sky” | Houses are described as “soft,” while people “pale,” giving human qualities to environment and showing contrast of safety vs. fear. |

| Satire | “Vivas / To baseball, milkshakes, and those sociologists” | Mocking celebration of stereotypical American symbols highlights the absurdity of forced patriotism. |

| Simile | “Blurred like photographs, in rain” | Compares the rushing crowds to blurred photos, emphasizing disorientation and motion. |

| Symbolism | “A dollar in my palm” | The dollar symbolizes exploitation—Mexican workers are reduced to cheap, disposable labor. |

| Tone (Humorous-Ironic) | “On the power of a great, silly grin” | The playful tone contrasts the serious theme of racial injustice, softening tragedy with ironic humor. |

Themes: “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

- Racial Identity and Stereotyping 🧑🤝🧑

- “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto powerfully explores the theme of racial identity and the pervasive stereotyping faced by Mexican-Americans, reflecting the speaker’s struggle to assert their American identity in a society quick to judge based on ethnicity. The poem begins with the speaker working in a factory, but the arrival of the border patrol disrupts this setting, as the boss assumes all workers are undocumented and urges them to flee: “Over the fence, Soto,” he shouted, / and I shouted that I was American.” This declaration of citizenship is dismissed with “No time for lies,” revealing the harsh reality of racial profiling, where the speaker’s Mexican heritage overshadows their legal status. The boss’s assumption that the speaker must be an immigrant underscores how societal biases reduce individuals to stereotypes, ignoring their true identity. The speaker’s eventual defiance, yelling “vivas / To baseball, milkshakes,” reclaims their American identity through cultural symbols, but the need to assert this identity highlights the ongoing tension of living between two worlds—Mexican by heritage, American by birth. This theme resonates because it captures the universal struggle of marginalized groups to be recognized for their full, complex identities rather than reductive assumptions.

- Resilience and Defiance 😄

- “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto celebrates the theme of resilience and defiance, showcasing the speaker’s ability to transform a moment of fear and oppression into one of triumph and joy. Forced to flee from border patrol despite being American, the speaker runs “from that industrial road to the soft / Houses,” a journey marked by physical and emotional endurance. The act of running, initially spurred by fear, becomes a powerful metaphor for pushing forward against adversity. The poem’s closing lines, where the speaker yells “vivas / To baseball, milkshakes, and those sociologists / Who would clock me / As I jog into the next century / On the power of a great, silly grin,” reflect an irrepressible spirit. The “great, silly grin” symbolizes defiance, turning a degrading situation into an assertion of individuality and optimism. By embracing American cultural icons like baseball and milkshakes, the speaker defies the stereotypes that seek to define them, running not just from danger but toward a hopeful future. This theme of resilience resonates widely, as it reflects the human capacity to find strength and humor in the face of injustice.

- Social Injustice and Prejudice 🚨

- “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto confronts the theme of social injustice and prejudice, exposing the systemic biases that marginalize Mexican-Americans and other minority groups. The poem’s pivotal moment occurs when the border patrol arrives, and the boss, without hesitation, assumes the speaker and others are undocumented: “‘No time for lies,’ he said, and pressed / A dollar in my palm, hurrying me / Through the back door.” This dismissive response to the speaker’s claim of being American reveals how prejudice overrides truth, forcing the speaker into a dehumanizing escape. The “amazed crowds that lined / The street” further highlight societal complicity, as their stares turn the speaker’s flight into a spectacle, reinforcing their alienation. The “dollar” pressed into the speaker’s hand symbolizes tokenism, a superficial gesture that underscores exploitation rather than addressing injustice. Soto’s critique of these systemic issues—racial profiling, workplace exploitation, and societal judgment—makes the poem a poignant commentary on the broader social structures that perpetuate inequality, resonating with readers who recognize these enduring challenges.

- Cultural Duality and Belonging 🏠

- “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto delves into the theme of cultural duality and the search for belonging, capturing the speaker’s navigation of their Mexican heritage and American identity. The poem juxtaposes the industrial factory, where the speaker is misidentified as an immigrant, with the “soft / Houses” of a suburban neighborhood, symbolizing a divide between the working-class, ethnic identity and the mainstream American world. The speaker’s assertion, “I shouted that I was American,” reflects their claim to belong in the U.S., yet the boss’s rejection and the need to flee “through the back door” highlight their exclusion from this identity. The poem’s closing celebration of “baseball, milkshakes” alongside the Spanish “vivas” blends American and Mexican cultural elements, illustrating the speaker’s embrace of both worlds. This duality is further emphasized by the ironic nod to “sociologists / Who would clock me,” suggesting external attempts to categorize the speaker’s identity. The poem’s exploration of belonging resonates with readers who experience the tension of living between cultures, seeking acceptance in a society that often demands conformity.

Literary Theories and “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

| Theory | Explanation | Reference from Poem | Application to the Poem |

| 🔍 New Historicism | Literature must be read in the context of its historical, cultural, and political moment. | “Until the border patrol opened / Their vans” | Reflects the U.S.–Mexico immigration context of the late 20th century. The speaker’s forced flight mirrors how Hispanic laborers were stereotyped as “illegal” regardless of citizenship. |

| 📖 Postcolonial Theory | Examines identity, race, and the lingering effects of colonial and imperial power on marginalized groups. | “I shouted that I was American. / ‘No time for lies,’ he said” | Despite citizenship, the speaker is treated as an “other.” The boss and border patrol reproduce colonial hierarchies where Mexicans are seen as outsiders, showing systemic racism. |

| 🌎 Marxist Theory | Focuses on class struggle, labor, exploitation, and the economic forces shaping human life. | “Pressed / A dollar in my palm, hurrying me / Through the back door” | The boss values the worker only for labor. The dollar symbolizes exploitation: Mexican workers are seen as replaceable and disposable under capitalist structures. |

| 👥 Reader-Response Theory | Meaning is created by the reader’s interaction with the text, influenced by personal and cultural background. | “What could I do but yell vivas / To baseball, milkshakes” | Different readers interpret this differently: ironic celebration of American culture, or assimilation. Mexican-American readers may feel frustration, while others may read it as humor. |

Critical Questions about “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

❓ Question 1: How does Soto portray the conflict between personal identity and imposed stereotypes in “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto?

In “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto, the speaker’s identity as an American citizen clashes with how others perceive him. When the boss shouts, “Over the fence, Soto,” and the speaker insists, “I shouted that I was American”, the denial of his truth reflects the imposition of stereotypes on Mexican-Americans. The boss’s response—“No time for lies”—underscores how racial profiling reduces him to a body in flight, regardless of his legal status. Soto shows that identity is not just what one claims but how it is recognized—or denied—by society. The irony is sharp: citizenship papers mean little when skin color and name trigger suspicion.

🔍 Question 2: In what ways does the poem critique labor exploitation and capitalist systems in “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto?

Soto exposes the exploitative nature of labor in “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto through the moment when the boss “pressed / A dollar in my palm, hurrying me / Through the back door.” This action reveals that the worker is seen only in terms of economic value, discarded the moment he becomes inconvenient. The dollar symbolizes both a payoff and an insult, showing how capitalist structures reduce workers to expendable commodities. The command to flee—while still on the boss’s “time”—ironically binds the worker to the system even in flight. Soto critiques not only individual prejudice but also the economic structures that profit from immigrant labor while simultaneously criminalizing it.

🌎 Question 3: How does the poem use imagery of running to symbolize displacement and resilience in “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto?

Running is the central motif and metaphor in “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto. The speaker confesses, “Since I was on his time, / I ran / And became the wag to a short tail of / Mexicans –” where the act of running becomes both literal escape and symbolic displacement. The enjambed lines mimic breathless movement, emphasizing the forced mobility of migrant laborers. Yet the running also suggests resilience and survival: he keeps moving past “amazed crowds” that blur “like photographs, in rain.” The final image—“jog into the next century / On the power of a great, silly grin”—turns running into a paradoxical triumph. Despite being chased, mocked, and reduced, the speaker reclaims dignity in persistence.

👥 Question 4: How does Soto use humor and irony to expose serious issues of race and belonging in “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto?

The closing lines of “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto reveal Soto’s use of humor and irony to critique cultural stereotypes. The speaker shouts “vivas / To baseball, milkshakes, and those sociologists”—a satirical celebration of mainstream American culture and academic observers. Baseball and milkshakes symbolize assimilation into U.S. identity, while the ironic mention of sociologists highlights how Mexican-Americans are studied but not truly understood. The humor of a “great, silly grin” contrasts with the injustice of being forced to flee despite citizenship. Soto demonstrates that laughter becomes a coping mechanism, allowing the speaker to undermine prejudice by embracing absurdity. The irony underscores that sometimes survival requires both endurance and mockery of the system that marginalizes you.

Literary Works Similar to “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

- 🌎 “Let America Be America Again” by Langston Hughes

Similarity: Like Soto, Hughes critiques the gap between American ideals and reality, showing how marginalized groups are excluded from the promised freedom. - 🚶 “Walking Around” by Pablo Neruda

Similarity: Neruda’s poem, like Soto’s, portrays the alienation of the working class, where daily survival feels dehumanizing and disorienting. - 🧱 “The Latin Deli: An Ars Poetica” by Judith Ortiz Cofer

Similarity: Cofer’s work, like Soto’s, explores Latino immigrant identity and the tension between assimilation and cultural preservation. - 🛂 “Refugee in America” by Langston Hughes

Similarity: Hughes, like Soto, captures the pain of belonging and unbelonging—citizenship does not erase the experience of racial discrimination. - 🚧 “Immigrants” by Pat Mora

Similarity: Mora’s poem, like Soto’s, shows how immigrant families struggle with identity, raising children to “be American” while never fully accepted as such.

Representative Quotations of “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

| Quotation | Context (Theoretical Perspective) | Interpretation |

| “At the factory I worked / In the fleck of rubber, under the press” 🏭 | Chicano Studies: The poem opens with the speaker in a labor-intensive factory setting, grounding the narrative in the working-class experience of Mexican-Americans. | The gritty imagery of “fleck of rubber” and “press” highlights the oppressive, industrial environment, symbolizing the socioeconomic struggles and exploitation faced by Chicano workers. |

| “Of an oven yellow with flame” 🔥 | Postcolonial Theory: The vivid description of the factory’s oven introduces a sense of danger and heat, reflecting the harsh conditions imposed on marginalized workers. | The “yellow” oven symbolizes both physical toil and the systemic pressures of a society that marginalizes ethnic minorities, evoking a colonial legacy of labor exploitation. |

| “Until the border patrol opened / Their vans” 🚨 | Critical Race Theory: The arrival of border patrol introduces racial profiling, disrupting the workplace and forcing the speaker into a dehumanizing flight. | This moment underscores systemic racism, as the assumption of illegality targets the speaker based solely on ethnicity, highlighting the pervasive fear of immigration enforcement. |

| ““Over the fence, Soto,” he shouted” 🗣️ | Chicano Studies: The boss’s command personalizes the speaker as “Soto,” reflecting the poet’s own identity, and signals the urgency of escape due to presumed illegality. | The direct address and command to flee over a fence reveal workplace complicity in racial assumptions, stripping the speaker of agency and reinforcing Chicano marginalization. |

| “and I shouted that I was American” 🇺🇸 | Critical Race Theory: The speaker asserts their American citizenship, which is dismissed, highlighting the conflict between their legal identity and societal perception. | This declaration exposes the irony of racial profiling, where the speaker’s Mexican heritage overshadows their American identity, illustrating the erasure of minority citizenship. |

| ““No time for lies,” he said” 🚫 | Postcolonial Theory: The boss’s dismissal of the speaker’s claim reflects a colonial mindset that assumes inferiority and illegitimacy of non-white identities. | The rejection of the speaker’s truth as a “lie” perpetuates a power dynamic where marginalized voices are silenced, reinforcing systemic prejudice. |

| “A dollar in my palm, hurrying me / Through the back door” 💵🚪 | Marxist Theory: The boss’s act of giving a dollar and pushing the speaker out symbolizes economic exploitation and tokenism in a capitalist system. | The “dollar” and “back door” represent superficial compensation and exclusion, highlighting how labor systems exploit and marginalize workers of color. |

| “I ran And became the wag to a short tail of Mexicans” 🐕 | Chicano Studies: The speaker leads a group of Mexican workers in flight, using a metaphor that suggests both leadership and dehumanization. | The “wag to a short tail” metaphor reflects the collective Chicano experience of being chased and stereotyped, yet also shows resilience in community solidarity. |

| “Ran past the amazed crowds that lined / The street and blurred like photographs, in rain” 👀🌧️ | Postcolonial Theory: The speaker’s flight through a public space, observed by onlookers, underscores their alienation and objectification as a spectacle. | The “amazed crowds” and simile of “blurred” photographs evoke colonial gazes, where the marginalized are reduced to objects of curiosity, their humanity obscured. |

| “What could I do but yell vivas / To baseball, milkshakes, and those sociologists / Who would clock me / As I jog into the next century / On the power of a great, silly grin” ⚾🥤😄 | Cultural Studies: The poem ends with the speaker defiantly embracing American culture while mocking societal scrutiny, symbolizing resilience and cultural duality. | The celebratory “vivas” to American icons and the “silly grin” transform oppression into triumph, blending Chicano pride with American identity, defying attempts to categorize them. |

Suggested Readings: “Mexicans Begin Jogging” by Gary Soto

Books

- Pérez-Torres, Rafael. Movements in Chicano Poetry: Against Myths, Against Margins. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Soto, Gary. New and Selected Poems. Raincoast Books, 1995.

Academic Articles

- Bowden, A. C. “Cultural and Linguistic Passages in the Poetry of Pat Mora … and Gary Soto.” Honors Undergraduate Thesis, Utah State University, 2011. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/94

- StudyCorgi. “Gary Soto: Biography and Soto’s Poems Analysis.” StudyCorgi, 22 Nov. 2021. https://studycorgi.com/gary-soto-biography-and-sotos-poems-analysis/

Poem Website

- StudyCorgi. “‘Mexicans Begin Jogging’ by Gary Soto.” StudyCorgi, 18 Mar. 2022. https://studycorgi.com/mexicans-begin-jogging-by-gary-soto/