Introduction: “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

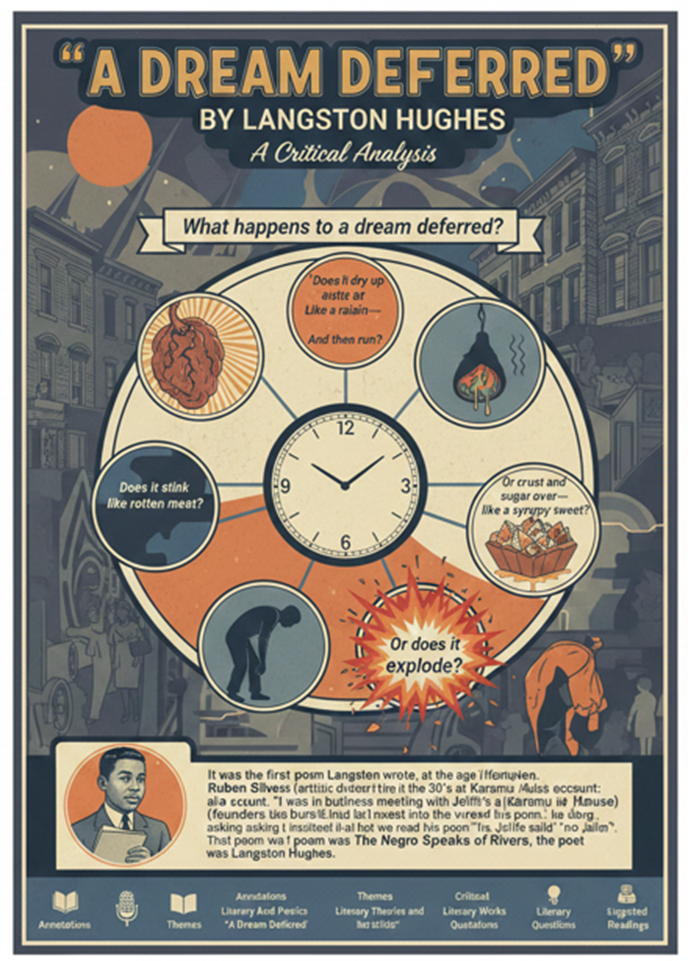

“A Dream Deferred” (better known by its published title “Harlem”) by Langston Hughes first appeared in 1951 in his book-length poem suite Montage of a Dream Deferred, where it crystallizes the suite’s central question about what prolonged racial and economic postponement does to Black aspirations in America. In eleven compressed lines, Hughes turns the abstract “dream” into a series of visceral consequences—“dry up / like a raisin in the sun,” “fester like a sore,” “stink like rotten meat,” or “crust and sugar over / like a syrupy sweet,” before it “sags / like a heavy load,” and finally threatens to “explode”—so the poem reads as both a warning and an indictment of enforced waiting. Its enduring popularity comes from this unforgettable chain of everyday, sensory images and relentless rhetorical questioning (“What happens to a dream deferred?”), which makes structural injustice feel immediate and bodily—while also echoing far beyond its moment (famously lending a key phrase to the title of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun).

Text: “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Annotations: “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

| Line | Text (as provided) | Annotation | Literary devices |

| 1 | What happens to a dream deferred? | Opens with a pressure-point question: postponing a “dream” (goal, dignity, freedom) doesn’t erase it—it changes it, and the poem investigates the consequences. | ❓ Rhetorical question · 🎯 Theme/Motif (deferred dream) · 🔮 Foreshadowing |

| 2 | Does it dry up | Suggests vitality draining away: delay can shrink possibility into lifelessness. | ❓ Rhetorical question · 🧠 Metaphor (dream as something organic) · 🔁 Parallel structure setup |

| 3 | Like a raisin in the sun? | A vivid simile: the dream becomes wrinkled/shriveled—once juicy, now diminished by exposure and time. | 🧪 Simile · 👁️ Visual imagery · 🍇 Symbolism (shriveled potential) · ❓ Rhetorical question |

| 4 | Or fester like a sore— | Delay doesn’t just “dry”; it can infect: a postponed dream may turn into pain, resentment, and harm that worsens internally. | 🧪 Simile · 🩹 Grotesque/medical imagery · ⚡ Diction (fester) · 🔁 Parallelism (“Or…”) |

| 5 | And then run? | Pushes the “sore” image to its ugly outcome: suppressed pain leaks out—private hurt becomes visible/social. The short line increases shock. | 👁️ Kinetic imagery · ✂️ Enjambment (carried from prior line) · ⏸️ Caesura (dash effect from line 4) |

| 6 | Does it stink like rotten meat? | Deferral becomes moral/social decay: the dream rots, producing a public “stink” (shame, corruption, humiliation, social unrest). | 🧪 Simile · 👃 Olfactory imagery · ⚡ Diction (stink/rotten) · ❓ Rhetorical question |

| 7 | Or crust and sugar over— | Another possibility: the dream hardens into a glossy cover—pain disguised as something “fine,” but actually sealed and rigid. | 🍬 Sensory (taste/texture) imagery · 🧠 Metaphor (masking/covering) · ⏸️ Caesura (dash/pause) · 🔁 Parallelism |

| 8 | like a syrupy sweet? | Sweetness becomes suspicious: it’s not nourishment but sticky concealment—surface pleasure covering unresolved deprivation. | 🧪 Simile · 🍬 Gustatory imagery · 🧵 Alliteration (“syrupy sweet”) |

| 9 | Maybe it just sags | Tone shifts to weary resignation: not rot or infection—just slow collapse under time and disappointment. | 🎭 Tone shift (speculation/resignation) · 🧍 Personification (dream “sags”) |

| 10 | like a heavy load. | The dream becomes weight: deferral burdens the person/community physically and psychologically—oppression as carried strain. | 🧪 Simile · 🏋️ Tactile/physical imagery · 🧠 Metaphor (dream as burden) |

| 11 | Or does it explode? | Climactic warning: prolonged deferral may culminate in rupture—anger, revolt, violence, or sudden transformation. The blunt ending intensifies urgency. | 💥 Explosive imagery / Metaphor · ❓ Rhetorical question · 📈 Climax · 🔄 Volta/turn (from “maybe” to threat) |

Themes: “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

🔴 The Destructive Nature of Inaction

In “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes, the poet explores the physical and psychological decay that occurs when a person’s fundamental aspirations are forced into a state of perpetual waiting. Rather than remaining static, the deferred dream undergoes a grotesque transformation, likened to a raisin drying in the sun or a festering sore that eventually runs with infection. This suggests that hope is a living entity that requires active pursuit to remain healthy; when it is denied, it does not simply vanish but instead putrefies within the individual’s psyche. The complex interplay between the “dry” and “festering” imagery illustrates a spectrum of suffering, ranging from the quiet shriveling of the spirit to the active, painful inflammation of resentment. Ultimately, Hughes argues that delaying justice or personal fulfillment is not a neutral act but a destructive one that poisons the dreamer from the inside out.

⚖️ The Weight of Systemic Oppression

The theme of psychological burden is central to “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes, specifically through the metaphor of a dream that “sags like a heavy load.” This imagery evokes the exhaustion inherent in the African American experience during the Jim Crow era, where the constant postponement of equality created a cumulative, crushing weight on the soul. Unlike the sharper metaphors of sores or rotten meat, the “heavy load” represents a chronic, wearying pressure that slows down the individual’s progress and dims their outlook on the future. Hughes masterfully uses this shift in tone to reflect how social stagnancy creates a wearying fatigue, implying that a dream deferred is not just a personal disappointment but a physical gravity that hinders entire communities. The sentence structures mirror this heaviness, suggesting that the long-term denial of opportunity eventually becomes a burden too massive for any single person to carry indefinitely.

🍏 The Illusion of Stagnant Peace

Within “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes, the poet considers whether a neglected ambition might “crust and sugar over—like a syrupy sweet,” presenting a chillingly deceptive form of decay. This theme highlights the danger of complacency or the “sweetening” of a bitter reality, where the dreamer might attempt to mask their disappointment with a hard, sugary exterior of feigned acceptance. However, this crusting is merely a surface-level transformation that hides the underlying loss of vitality, much like a confection that has sat too long and become unpalatable. By using this domestic, seemingly innocent metaphor, Hughes suggests that even when a deferred dream appears to have settled into a harmless state of sugary stillness, it remains a distorted version of its original self. The complexity of this theme lies in the realization that a “sweetened” dream is just as dead as a “rotten” one, representing a total loss of the dream’s original, nourishing potential.

💥 The Inevitability of Social Explosion

The final and most haunting theme of “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes is the potential for a sudden, violent release of long-repressed energy, encapsulated in the closing question, “Or does it explode?” This theme serves as a prophetic warning regarding the consequences of societal neglect and the systemic blocking of progress for marginalized groups. When dreams are deferred through generations, the internal pressure of resentment, grief, and unfulfilled energy builds to a critical point where it can no longer be contained by “sagging” or “festering.” This explosion represents a total breakdown of the status quo, suggesting that if the internal rot of a deferred dream is not addressed through justice, it will inevitably manifest as external upheaval. Hughes uses this brief, emphatic ending to shatter the previous metaphors of slow decay, replacing them with a singular, inevitable moment of volatile transformation that demands the reader’s immediate attention and reflection.

Literary Theories and “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

| Literary Theory | Core Perspective & Analysis | References from the Poem |

| Marxist Criticism 💰 | Focuses on power dynamics, class struggle, and the material conditions of the dreamer. It views the “deferred” dream as a result of socioeconomic barriers that prevent marginalized individuals from achieving prosperity. | “like a heavy load” (the physical weight of labor and poverty); “rotten meat” (the waste of human potential in a capitalist system). |

| Post-Colonial / African American Criticism ✊🏾 | Examines the poem as a reflection of the Black experience in America. It analyzes the “deferred” dream as the promise of the “American Dream” which is systematically denied to people of color. | “Does it dry up / like a raisin in the sun?” (the historical context of the Great Migration and Southern roots); “Or does it explode?” (the threat of racial uprising). |

| Formalism / New Criticism 🔍 | Ignores outside history and focuses strictly on the text’s mechanics—rhyme, meter, and imagery. It looks at how the series of similes creates a sensory “pile-on” that builds tension. | The use of italics for the final line; the structural shift from sensory decay (smell/taste) to physical action (“sags”, “explode”). |

| Psychoanalytic Criticism 🧠 | Analyzes the poem through the lens of the human psyche, specifically looking at “repression.” The “festering sore” represents the psychological trauma of keeping desires bottled up until they become toxic. | “fester like a sore— / And then run?” (the internal “leaking” of suppressed trauma); “Maybe it just sags” (the onset of clinical depression and hopelessness). |

Critical Questions about “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

🟣 Q1. How does the poem connect the “deferred dream” to collective racial injustice rather than a purely private disappointment?

“A Dream Deferred” — Langston Hughes frames the dream as something structurally postponed, not merely personally abandoned, because the speaker’s question is posed in a public register—urgent, communal, and ethically charged—so that “deferred” reads as a social condition imposed by power rather than a choice made by an individual. When Hughes cycles through images of drying, festering, rotting, and sagging, he implies that sustained blockage corrodes the inner life of a community, even as it deforms the public atmosphere around it; consequently, the poem’s “dream” becomes a figure for dignity, opportunity, and recognized humanity that has been repeatedly delayed. Moreover, by refusing to name the dream explicitly, Hughes invites the reader to hear what history already supplies—segregation, exploitation, humiliation—while keeping the poem transferable to other withheld futures. In that way, the poem converts private longing into civic critique.

🟠 Q2. Why does Hughes rely so heavily on bodily, food, and sensory imagery, and what argument does that imagery make?

“A Dream Deferred” — Langston Hughes uses the body and the senses because oppression is not abstract; it is felt, endured, and metabolized, and the poem’s metaphors insist that delay enters the bloodstream of everyday life. The raisin, sore, rotten meat, syrupy sweet, and heavy load are not decorative comparisons; rather, they dramatize how postponed aspiration changes texture over time—shriveling, infecting, decaying, hardening, or weighing down—so that the dream becomes increasingly difficult to recover in its original form. Importantly, the images also move between the intimate and the social: a sore is private until it “runs,” while rotten meat stinks outwardly, suggesting that injustice cannot be quarantined, even if the harmed are expected to suffer silently. By choosing sensory images, Hughes argues that deferred justice produces real consequences—psychological, moral, and political—that eventually become unavoidable to everyone.

🟢 Q3. How do structure and sound—short lines, repeated questions, and the escalating sequence—shape the poem’s meaning and tension?

“A Dream Deferred” — Langston Hughes builds pressure through a deliberately compressed architecture, since the poem’s brief, jagged lines mimic a mind returning again and again to the same unresolved problem, while the repetition of “Does it…?” and “Or…?” creates a prosecutorial rhythm that feels like cross-examination. Because each question offers an image that is more troubling or more consequential than the last, the poem behaves like a tightening coil: the reader is pulled forward by alternation and suspense, even as the poem refuses the comfort of a definitive answer. The dashes and line breaks function like controlled interruptions, so that meanings arrive in bursts—“fester like a sore— / And then run?”—where the pause becomes a hinge between concealed suffering and public leakage. This formally enacted escalation makes the final line feel less like a surprise than a verdict whose inevitability the poem has been preparing all along.

🔴 Q4. What does the final possibility—“Or does it explode?”—suggest about violence, rebellion, and responsibility, and how should readers interpret it ethically?

“A Dream Deferred” — Langston Hughes ends with “explode” to name the political risk produced when legitimate hopes are systematically postponed, because the poem implies that social stability cannot be purchased by indefinitely denying people their futures, even if silence and patience are demanded of them. Yet the line is ethically complicated: it can register as a warning about destructive upheaval, while also sounding like an accusation aimed at the conditions that make eruption thinkable, which means responsibility shifts from the “exploding” to the forces that keep deferring. The poem’s ambiguity is strategic, since “explosion” may be literal violence, but it may also be psychic rupture, mass protest, or sudden historical change that shatters old arrangements. By asking rather than declaring, Hughes forces readers to confront causality: if a society repeatedly blocks rightful aspirations, it manufactures its own crisis, and the moral question becomes not whether explosion is “bad,” but why deferral was treated as acceptable in the first place.

Literary Works Similar to “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

- 🟣 “If We Must Die” by Claude McKay — Like Langston Hughes’s “A Dream Deferred”, it channels the pressure of racialized oppression into a tight warning that prolonged degradation demands a reckoning—whether through defiant resistance or explosive consequence.

- 🟠 “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar — Similar to “A Dream Deferred”, it exposes how sustained injustice forces a community to conceal pain publicly, until hidden suffering becomes psychologically corrosive and socially unsustainable.

- 🟢 “For My People” by Margaret Walker — Like “A Dream Deferred”, it speaks in a collective voice about systemic deprivation and delayed dignity, turning postponed hope into a call for moral and political transformation.

- 🔴 “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou — In the same spirit as “A Dream Deferred”, it confronts racist constraint and refuses the shrinking of aspiration, insisting that repeated attempts to suppress a people’s future only intensify their resolve to rise.

Representative Quotations of “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical perspective |

| 💭 “What happens to a dream deferred?” | Context: A community’s aspirations are repeatedly postponed by unequal social structures, turning hope into a public problem rather than a private feeling. | Critical Race Theory: Deferred desire signals systemic racism—delay is not neutral; it is an instrument that manages and contains Black mobility and rights. |

| 🌞 “Does it dry up / Like a raisin in the sun?” | Context: Time and deprivation shrink possibilities; what was “fresh” with promise becomes withered under persistent hardship. | New Historicism: The image resonates with mid-century urban Black life—crowding, exclusion, and limited opportunity shaping what “the dream” can become. |

| 🩹 “Or fester like a sore—” | Context: Unmet needs don’t simply wait; they worsen, like an untreated wound in a body denied care. | Psychoanalytic (repression/symptom): Postponed desire returns as pathology—what is pushed down resurfaces as psychic and social “infection.” |

| 🩸 “And then run?” | Context: The consequence of neglect becomes visible and uncontrollable—damage spills into daily life and relationships. | Trauma Studies: The “running” wound suggests unresolved injury that leaks into the present, disrupting normality through recurring pain. |

| 🦨 “Does it stink like rotten meat?” | Context: Prolonged neglect produces public ugliness—social decay that cannot be hidden and forces recognition. | Marxist / Materialist Critique: Rot evokes material conditions—poverty, exploitation, and abandonment that make “dreams” spoil in the first place. |

| 🍬 “Or crust and sugar over—” | Context: Sometimes suffering is masked—appearing “fine” on the surface while harm hardens underneath. | Ideology Critique: Sweet “crust” symbolizes false consolation (token progress, empty slogans) that covers injustice without curing it. |

| 🍯 “like a syrupy sweet?” | Context: The delayed dream may become sentimentalized—turned into a sticky, superficial comfort rather than real change. | Cultural Studies: “Syrupy” suggests commodified pleasure—culture packaging pain into palatable narratives that pacify demands for justice. |

| 🧱 “Maybe it just sags” | Context: The most common outcome may be exhaustion—hope droops under repeated disappointment. | Affect Theory: The line captures the slow violence of attrition—emotional fatigue and diminished capacity produced by chronic deferral. |

| 🏋️ “like a heavy load.” | Context: The deferred dream becomes a burden carried daily—weight that shapes posture, pace, and survival. | Intersectional Social Theory: A “load” frames inequality as lived labor—people absorb structural pressure into the body and routine. |

| 💥 “Or does it explode?” | Context: When postponement reaches a limit, frustration can turn into rupture—social unrest, revolt, or breakdown. | Postcolonial / Fanonian Lens: The “explosion” reads as the return of denied humanity—when containment fails, pressure converts into collective confrontation. |

Suggested Readings: “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

Books

- Hughes, Langston. Montage of a Dream Deferred. Henry Holt, 1951.

- Hughes, Langston. The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. Edited by Arnold Rampersad and David E. Roessel, Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Academic Articles

- Dualé, Christine. “Langston Hughes’s Poetic Vision of the American Dream: A Complex and Creative Encoded Language.” Angles: New Perspectives on the Anglophone World, no. 7, 2018, OpenEdition Journals, https://journals.openedition.org/angles/920. Accessed 30 Jan. 2026.

- Hartman, Michelle. “Dreams Deferred, Translated: Radwa Ashour and Langston Hughes.” CLINA: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Translation, Interpreting and Intercultural Communication, vol. 2, no. 1, 2016, pp. 61–76.

- https://gredos.usal.es/bitstream/handle/10366/131324/La_traduccion_de_Dreams_Deferred_Radwa_A.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1. Accessed 30 Jan. 2026.

Poem Websites

- Hughes, Langston. “Harlem.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46548/harlem. Accessed 30 Jan. 2026.

- Hughes, Langston. “Harlem.” Academy of American Poets, Poets.org, https://poets.org/poem/harlem-0. Accessed 30 Jan. 2026.