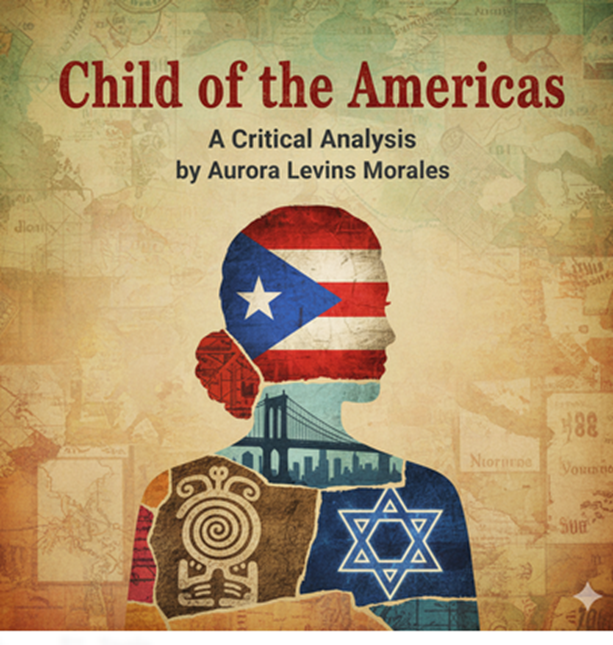

Introduction: “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

“Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales first appeared in 1986 in her collection Getting Home Alive, co-authored with Rosario Morales. The poem articulates the layered identity of a U.S. Puerto Rican Jew who embodies multiple diasporas—Caribbean, Jewish, African, Taíno, and European—woven into the fabric of American experience. Its main ideas revolve around hybridity, cultural inheritance, displacement, and the affirmation of wholeness despite fragmented histories. Through lines such as “I am new. History made me. My first language was spanglish. / I was born at the crossroads / and I am whole,” Morales rejects the notion of divided identity and instead celebrates multiplicity as strength. The poem gained popularity for its resonant exploration of immigrant and diasporic identity, its lyrical embrace of Spanglish as a legitimate linguistic medium, and its political assertion that American identity is inherently plural. This combination of personal narrative and cultural affirmation positioned the poem as a powerful voice in Latina feminist and multicultural literature of the late 20th century.

Text: “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

I am a child of the Americas,

a light-skinned mestiza of the Caribbean,

a child of many diaspora, born into this continent at a crossroads.

I am a U.S. Puerto Rican Jew,

a product of the ghettos of a New York I have never known.

An immigrant and the daughter and granddaughter of immigrants.

I speak English with passion: it’s the tongue of my consciousness,

a flashing knife blade of crystal, my tool, my craft.

I am Caribeña, island grown. Spanish is in my flesh,

Ripples from my tongue, lodge in my hips:

the language of garlic and mangoes,

the singing of poetry, the flying gestures of my hands.

I am of Latinoamerica, rooted in the history of my continent:

I speak from that body.

I am not African.

Africa is in me, but I cannot return.

I am not taína.

Taíno is in me, but there is no way back.

I am not European.

Europe lives in me, but I have no home there.

I am new. History made me. My first language was spanglish.

I was born at the crossroads

and I am whole.

(1986)

Annotations: “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

| Stanza (Lines) | Detailed Annotation | Literary Devices |

| 1. “I am a child of the Americas… my tool, my craft.” | The speaker defines her layered identity as Caribbean, Jewish, immigrant, and mestiza, highlighting the complexity of belonging across multiple diasporas. Her pride in English shows it as both survival and artistry, describing it as “the tongue of my consciousness” and a “flashing knife blade of crystal” to emphasize its precision and power. | 🌍 Metaphor (“flashing knife blade of crystal”) ✨ Symbolism (English = consciousness, identity) 🌸 Repetition (“child of”) 🔥 Juxtaposition (New York “I have never known”) |

| 2. “I am Caribeña, island grown… I speak from that body.” | Here the speaker roots herself in Caribbean and Latin American heritage. Spanish is portrayed not only as a language but as part of her body—embedded in tongue, hips, and gestures. Food, rhythm, and poetry illustrate how culture is lived through the senses. The stanza emphasizes identity as embodied history and tradition. | 🌊 Imagery (garlic, mangoes, singing, gestures) 🌸 Personification (“Spanish is in my flesh”) 🌍 Metaphor (language = body and roots) ✨ Sensory details (taste, sound, motion) |

| 3. “I am not African… I have no home there.” | This stanza engages with ancestral memory. The speaker acknowledges African, Taíno, and European heritage but stresses displacement and historical rupture. She embodies these legacies internally but has no direct home or return to them, underscoring the complexity of colonial history and diasporic identity. | 🌸 Anaphora/Repetition (“I am not…”) 🌍 Paradox (heritage present but no return) ✨ Allusion (African, Taíno, European) 🔥 Contrast (identity vs. belonging) |

| 4. “I am new… and I am whole.” | The closing stanza embraces hybridity as strength and completeness. The speaker credits history with shaping her and celebrates Spanglish as a natural product of blended cultures. The “crossroads” symbolizes both conflict and creativity, and the declaration “I am whole” asserts identity not as fragmented but as unified and empowering. | 🌍 Symbolism (crossroads = intersection of cultures) ✨ Affirmation (“I am whole”) 🌸 Metaphor (history “made” me) 🔥 Code-switching (Spanglish as identity marker) |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

| Device | Example from Poem | Explanation |

| 2. Allusion ✨ | “I am not taína. Taíno is in me” | References to African, Taíno, and European heritage allude to colonization, slavery, and indigenous history. |

| 3. Anaphora 🔥 | “I am not African. / I am not taína. / I am not European.” | Repetition at the beginning of clauses emphasizes denial of single roots while showing internal plurality. |

| 4. Assonance 🌊 | “I speak English with passion” | Repetition of the vowel sound “ea” adds musicality and flow to her declaration. |

| 5. Code-Switching 🌍 | “My first language was spanglish.” | Blending Spanish and English symbolizes hybridity and identity shaped at cultural crossroads. |

| 6. Contrast 🔥 | “Africa is in me, but I cannot return.” | Highlights the tension between ancestral presence and impossibility of return. |

| 7. Enumeration 🌸 | “U.S. Puerto Rican Jew” | Listing multiple identities showcases the layering and hybridity of her cultural self. |

| 8. Hyperbole ✨ | “Spanish is in my flesh” | Exaggeration to stress how deeply language and culture are embodied. |

| 9. Imagery 🌊 | “the language of garlic and mangoes” | Sensory description evokes taste, smell, and cultural richness of Caribbean life. |

| 10. Juxtaposition 🔥 | “A New York I have never known.” | Contrasts lived reality and inherited memory, highlighting immigrant displacement. |

| 11. Metaphor 🌍 | “English… a flashing knife blade of crystal” | Compares language to a knife for sharpness and clarity, suggesting power and danger. |

| 12. Paradox ✨ | “I am not African. Africa is in me.” | Contradiction reveals the complexity of diasporic identity—present yet unreachable. |

| 13. Personification 🌸 | “Spanish is in my flesh… lodge in my hips” | Treats language as a living force embodied in the body, not just spoken. |

| 14. Repetition 🔥 | “I am… I am…” | Repeated use of “I am” emphasizes affirmation of self-identity. |

| 15. Sensory Details 🌊 | “garlic and mangoes, / the singing of poetry” | Appeals to taste, smell, and sound, grounding cultural memory in the senses. |

| 16. Simile ✨ | “English… a flashing knife blade of crystal” (implied simile) | Suggests English is as sharp and clear as crystal, using comparison imagery. |

| 17. Symbolism 🌍 | “crossroads” | Represents the intersection of cultures, diasporas, and history. |

| 18. Synecdoche 🌸 | “my hips” / “my hands” | Body parts stand for the whole person, embodying cultural expression. |

| 19. Tone ✨ | “I am whole.” | The assertive, celebratory tone conveys empowerment and pride in hybrid identity. |

| 20. Voice 🔥 | Entire poem as “I” | The strong first-person voice gives authenticity, agency, and authority to her identity. |

Themes: “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

1. The Complexities of Identity

“Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales explores the intricate and multifaceted nature of identity, portraying it not as a singular, fixed concept but as a blend of various cultures, histories, and languages. The poem’s title itself, “Child of the Americas,” immediately establishes a broad, continental identity that transcends national borders. Morales refers to herself as a “light-skinned mestiza of the Caribbean,” highlighting her mixed heritage and the historical intersections that shaped her. She further complicates this by identifying as a “U.S. Puerto Rican Jew,” showcasing the diaspora she is a product of—the “ghettos of a New York I have never known” and her family’s immigrant past. Her identity is a composite of these elements, a dynamic and evolving self that is “new,” forged by a history that “made me.” She confidently asserts her wholeness despite being born “at a crossroads,” suggesting that her identity is complete precisely because of its diverse and intersecting parts.

2. Language as a Tool of Identity

“Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales powerfully portrays language as more than just a means of communication; it’s a fundamental aspect of identity and self-expression. The poet’s relationship with English is described as a passionate and deliberate choice—”it’s the tongue of my consciousness, a flashing knife blade of crystal, my tool, my craft.” This vivid imagery shows English as a sharp, precise instrument she uses to shape her thoughts and creativity. In contrast, Spanish is an inherent, physical part of her. She says, “Spanish is in my flesh,” and it “lodges in my hips,” using sensory language to describe a deep, visceral connection to her Caribbean roots. Spanish is the “language of garlic and mangoes” and the “flying gestures of my hands,” representing a cultural and embodied knowledge that is distinct from her intellectual use of English. The final line, “My first language was spanglish,” unifies these two linguistic worlds, confirming that her identity is not about choosing one language over the other but embracing the unique hybrid that reflects her lived experience.

3. The Sense of Not Belonging and Finding Wholeness

A central theme in “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales is the feeling of not fully belonging to any single place, culture, or heritage. The poem’s third stanza is a poignant litany of this displacement: “I am not African… I cannot return,” “I am not taína… there is no way back,” and “I am not European… I have no home there.” Morales acknowledges that each of these ancestral threads—Africa, the indigenous Taíno people, and Europe—is “in me” or “lives in me,” but she feels an insurmountable distance from their origins. This sense of being a product of many places yet belonging to none is a common immigrant experience. However, the poem takes a powerful turn in its conclusion. Despite this feeling of being at a crossroads, she asserts, “and I am whole.” This statement redefines what it means to belong. Instead of finding wholeness by returning to a single origin, she finds it in the very fact of her blended, diasporic identity. Her wholeness is not a lack of fragmentation but a confident acceptance of her unique and complex self.

4. The Impact of Diaspora and History

“Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales is a testament to the profound and lasting impact of diaspora and history on personal identity. The poem’s title and opening lines immediately place the speaker as “a child of many diaspora,” recognizing her identity as a direct result of historical movements and migrations. The poet is a “product of the ghettos of a New York I have never known,” connecting her present to the struggles and experiences of previous generations of immigrants. She is “rooted in the history of my continent” and speaks “from that body,” indicating that her physical and spiritual self is inextricably linked to the historical landscape of the Americas. The poem highlights that identity is not just a personal matter but a collective one shaped by global forces. Morales’s identity is not self-created but is “new” and “made” by the histories of forced migration, colonization, and cultural blending that have defined the Americas. Her final declaration of being “whole” despite this historical weight is a powerful assertion of resilience and self-acceptance.

Literary Theories and “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

| Literary Theory | Core Concepts and Application to “Child of the Americas” |

| Postcolonialism 🌍 | This theory examines the legacy of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on themes of identity, culture, and power in societies that were once colonized. Aurora Levins Morales’s poem is a quintessential postcolonial text. She navigates the complex identity of being a “U.S. Puerto Rican Jew” and a “light-skinned mestiza of the Caribbean,” a product of histories shaped by colonial powers (Spain, the U.S.) and global migrations. The line “I am not African… I cannot return. I am not taína… there is no way back. I am not European… I have no home there” directly addresses the fragmentation and displacement caused by colonial histories and diasporas, where a person is a mix of cultures but can’t fully claim any one origin as “home.” |

| Feminist Criticism ♀️ | Feminist criticism analyzes how literature reflects and shapes gender roles, power dynamics, and the experiences of women. While not overtly about gender, the poem can be read through a feminist lens by examining how Morales asserts her agency and defines her identity on her own terms, separate from male-dominated or patriarchal narratives. Her self-definition as “I am a child of the Americas” and “I am whole” is a powerful act of self-authorship. The description of language as a physical, embodied experience—”Spanish is in my flesh, Ripples from my tongue, lodge in my hips”—connects her linguistic and cultural identity to her physical body, a common theme in feminist writing that reclaims the female body as a site of knowledge and power. |

| New Historicism 📜 | This theory views a literary text as a product of its historical context, arguing that literature is not an isolated artifact but is deeply intertwined with the politics, culture, and social norms of the time it was written. “Child of the Americas” (1986) is a powerful example. It directly engages with the historical context of late 20th-century immigration, the rise of a distinct Spanglish culture, and the complexities of being a multicultural citizen in the United States. Morales’s reference to being “a product of the ghettos of a New York I have never known” and being “born into this continent at a crossroads” grounds the poem in specific socio-historical realities of diaspora and migration that were shaping American identity at the time. |

| Reader-Response Criticism 📖 | This theory focuses on the reader’s role in creating the meaning of a text. Meaning is not inherent in the text itself but is constructed through the interaction between the reader and the text. A reader-response analysis of “Child of the Americas” would explore how different readers—depending on their own cultural background, heritage, or experiences with immigration—would interpret the poem. For instance, a reader from a single-heritage background might be challenged by the poem’s complex layers of identity, while a reader from a mixed-race or immigrant background might feel a strong sense of kinship and validation in Morales’s declaration of being “whole.” The poem’s meaning, therefore, changes and deepens based on the unique lens each reader brings to it. |

Critical Questions about “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

🌍 Question 1: How does “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales redefine the meaning of “American” identity?

Answer: In “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales, American identity is redefined as plural, layered, and born of multiple diasporas rather than singular or uniform. Morales identifies herself as “a light-skinned mestiza of the Caribbean” and “a U.S. Puerto Rican Jew,” showing that her American identity is not rooted in one tradition but in the intersection of many. By declaring, “I was born at the crossroads / and I am whole,” she reframes hybridity as a source of wholeness rather than fragmentation. Her insistence that her “first language was spanglish” further resists assimilationist notions of what it means to be American, celebrating linguistic mixture as a marker of belonging. Thus, Morales redefines being American as embracing multiplicity, showing that hybridity is the authentic fabric of the Americas.

✨ Question 2: In what ways does “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales present language as both a tool of survival and a marker of cultural identity?

Answer: In “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales, language embodies both survival in America and cultural inheritance. English is described as “the tongue of my consciousness, / a flashing knife blade of crystal, my tool, my craft,” which frames it as precise, empowering, and necessary for her intellectual expression and survival in a U.S. context. In contrast, Spanish is portrayed as visceral and embodied: “Spanish is in my flesh… lodge in my hips,” tied to food, music, and gesture, such as “garlic and mangoes” and “the singing of poetry.” This contrast reveals English as instrumental and rational while Spanish functions as cultural memory and emotional connection. Her embrace of Spanglish—the fusion of both—demonstrates language as a marker of hybridity, where survival and identity merge. Morales shows that bilingualism is not conflict but strength, allowing her to claim belonging in both cultural worlds.

🔥 Question 3: How does “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales explore historical displacement and the impossibility of return?

Answer: In “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales, the theme of displacement is central to her identity, as she acknowledges the presence of ancestral legacies while recognizing the impossibility of returning to them. The stanza “I am not African. / Africa is in me, but I cannot return. / I am not taína… / I am not European” highlights how history, colonization, and slavery have fractured direct connections to origins. These repetitions stress that while her body carries traces of Africa, Taíno, and Europe, she cannot reclaim them as homelands. Instead, identity emerges in the present, forged out of memory and displacement. By rejecting the idea of “return,” Morales reframes the diasporic experience: identity is not about recovering a lost past but about embracing a new cultural self born of survival, migration, and history.

🌸 Question 4: How does the affirmation of wholeness in “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales reshape narratives of fragmented identity?

Answer: In “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales, the closing affirmation “I am whole” directly challenges narratives that view mixed or diasporic identities as incomplete. After tracing her roots across Africa, Europe, Taíno heritage, Puerto Rico, and Jewish diaspora, Morales concludes not with loss but with empowerment: “I am new. History made me. My first language was spanglish. / I was born at the crossroads / and I am whole.” The “crossroads” symbolizes both struggle and creation, and by embracing it, she transforms fragmentation into unity. Her declaration reshapes identity by refusing the assimilationist demand to erase difference in order to belong. Instead, she asserts that wholeness arises precisely from multiplicity and historical complexity. Thus, Morales reclaims hybridity as a powerful, self-affirming identity, rejecting deficit models of cultural mixing.

Literary Works Similar to “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

- “Heritage” by Countee Cullen: This poem shares a similar exploration of fragmented identity, with the speaker grappling with a deep, ancestral connection to Africa that he has never seen, similar to Morales’s feeling that “Africa is in me, but I cannot return.”

- “Biracial” by Carolyn Oxley: Like Morales’s work, this poem directly confronts the societal gaze and expectations placed on individuals of mixed heritage, asserting a sense of wholeness and individual identity beyond a simple classification.

- “On My Tongue” by Alycia Pirmohamed: This poem explores the intimate and often complex relationship with language and its connection to cultural heritage, resonating with Morales’s detailed descriptions of English as a tool of consciousness and Spanish as being “in my flesh.”

- “Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border” by Alootook Ipellie: This title itself captures the same “at a crossroads” sentiment found in Morales’s poem, portraying the experience of living between two distinct cultural worlds and finding a way to be whole within that space.

- “I, Too” by Langston Hughes: This poem shares a common thread of asserting one’s identity and belonging within a larger, often exclusionary, national context, with Hughes’s “I, too, sing America” mirroring Morales’s confident declaration of being “a child of the Americas” and “whole.”

Representative Quotations of “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

| Quote & Context | Theoretical Concept |

| 🌍 “I am a child of the Americas, / a light-skinned mestiza of the Caribbean, / a child of many diaspora, born into this continent / at a crossroads.” Context: The poem’s opening lines establish the speaker’s complex, multicultural identity shaped by migration and diverse heritages. | Postcolonialism: This quote embodies postcolonial identity, which is often a hybrid and fragmented product of historical movements, colonialism, and the mixing of cultures. The term “mestiza” itself is a product of colonial history. |

| ♀️ “I speak English with passion: it’s the tongue of my consciousness, / a flashing knife blade of crystal, my tool, my craft.” Context: The speaker describes her relationship with the English language, portraying it as a deliberate choice and a powerful instrument for self-expression and creation. | Feminist Criticism: This imagery presents language not as a passive inheritance but as an actively wielded tool, a form of intellectual and creative power, which is a key theme in feminist discourse on female agency and voice. |

| 📜 “I am a U.S. Puerto Rican Jew, / a product of the ghettos of a New York I have never / known.” Context: The speaker links her personal identity to the historical and social conditions of her ancestors, connecting her present to a past she did not personally experience. | New Historicism: This quote directly connects the individual to a specific historical and social context—the urban ghettos of New York that shaped immigrant and Jewish American identities, even for those who did not live there. |

| 📖 “I am Caribeña, island grown. Spanish is in my flesh, / Ripples from my tongue, lodge in my hips:” Context: The speaker describes her connection to the Spanish language and Caribbean culture as a physical, embodied, and deeply ingrained part of her being. | Reader-Response Criticism: A reader with a similar cultural background might immediately connect with this physical description of language and culture, feeling a strong sense of validation. The meaning is generated by the reader’s own embodied experience. |

| 📜 “An immigrant and the daughter and granddaughter of / immigrants.” Context: This line explicitly states the family history of migration that has defined the speaker’s life and identity. | New Historicism: This simple statement is a historical fact that provides crucial context for understanding the speaker’s identity as a product of continuous migration, a defining characteristic of American history. |

| 🌍 “I am not African. / Africa is in me, but I cannot return. / I am not taína. / Taíno is in me, but there is no way back.” Context: The speaker reflects on her ancestral ties to different parts of the world, acknowledging the connection but also the impossibility of a physical or cultural return. | Postcolonialism: This quote powerfully illustrates the sense of displacement and un-homeliness often felt by people in postcolonial societies, who carry the legacy of multiple cultures but belong fully to none of them. |

| ♀️ “I am of Latinoamerica, rooted in the history of my / continent: / I speak from that body.” Context: The speaker claims a continental identity, explicitly linking her voice and perspective to the collective history and “body” of Latin America. | Feminist Criticism: This assertion of speaking from “that body” is a feminist act of reclaiming and centering one’s own corporeal and cultural experience as the source of truth and knowledge, rather than relying on external or male-defined authority. |

| 📖 “My first language was spanglish.” Context: The speaker reveals her unique linguistic origin, a hybrid language born of cultural mixing. | Reader-Response Criticism: This line would resonate differently with various readers. For a native Spanish or English speaker, it might represent a “broken” language, while for someone from a bicultural background, it would be a powerful affirmation of a shared, valid linguistic identity. |

| 📜 “I was born at the crossroads” Context: The speaker repeatedly uses this metaphor to describe her birth and identity, highlighting the intersection of cultures and histories that define her. | New Historicism: “Crossroads” is a historical metaphor, representing the meeting points of different cultures and migrations that have shaped the Americas, from the Columbian Exchange to modern immigration patterns. |

| 🌍 “and I am whole.” Context: The poem’s final, single-line sentence serves as a powerful conclusion, a confident declaration of self-acceptance and integrity. | Postcolonialism: This line offers a hopeful counter-narrative to the fragmentation often associated with postcolonial identity. It suggests that wholeness isn’t found in a singular, pure origin but in the very act of embracing a complex, blended, and diasporic self. |

Suggested Readings: “Child of the Americas” by Aurora Levins Morales

Books

- Morales, Aurora Levins, and Rosario Morales. Getting Home Alive. Firebrand Books, 1986.

- Morales, Aurora Levins. The Story of What Is Broken Is Whole: An Aurora Levins Morales Reader. Duke University Press, 2024.

Academic Articles

- Junquera, Carmen Flys. “Grounding Oneself at the Crossroads: Getting Home Alive by Aurora Levins Morales and Rosario Morales.” Atlantis: Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 47–67.

https://atlantisjournal.org/index.php/atlantis/article/download/320/243/2088 - Cristian, Réka M. “Healing Processes in Aurora Levins Morales’s Remedios and Medicine Stories.” PJAS (Polish Journal of American Studies), 2025.

https://paas.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/18-5-cristian.pdf

Websites

- “Voices of Feminism Oral History Project: Morales, Aurora.” Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Interview transcript by Kelly Anderson, 2005.

https://www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/ssc/vof/transcripts/LevinsMorales.pdf - “Aurora Levins Morales.” Jewish Women’s Archive.

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/morales-aurora-levins