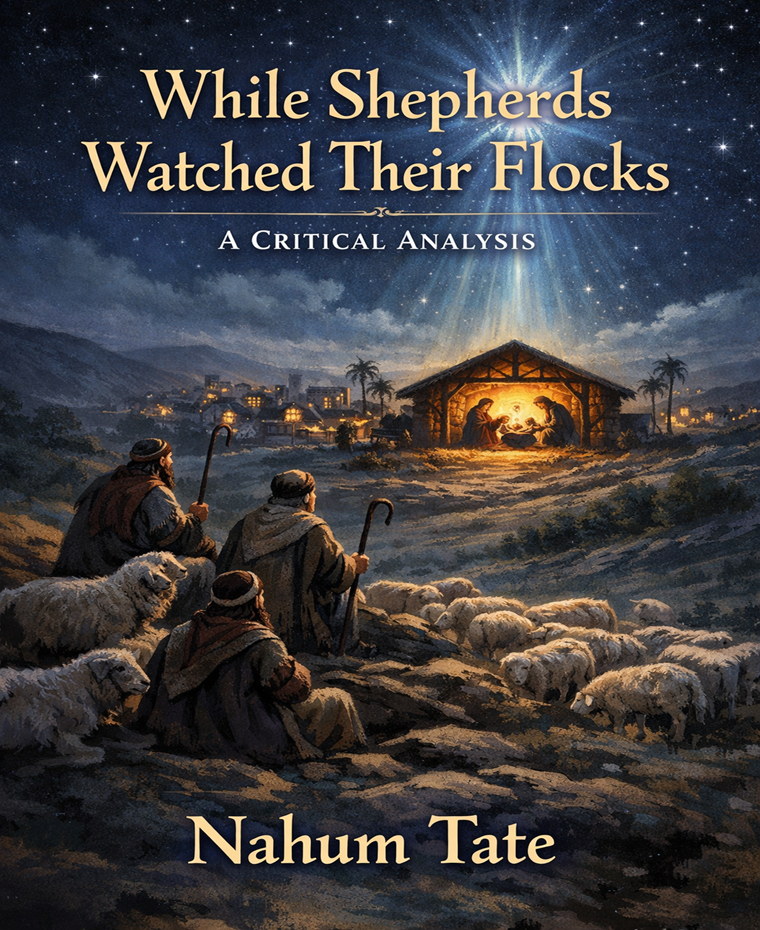

Introduction: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

“While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate: first appeared in 1700, published in A Supplement to the New Version of the Psalms of David (the Tate–Brady supplement to their 1696 psalter collection), where it circulated as a singable, congregational retelling of Luke’s Nativity scene. Its central ideas are the ordinary world interrupted by revelation (“an angel of the Lord came down, / and glory shone around,” stanza 1), fear transformed into assurance (“Fear not,” stanza 2), and the universal scope of the Incarnation (“glad tidings of great joy…to you and all mankind,” stanza 2), culminating in a deliberately plain “sign” of divine humility (“wrapped in swaddling clothes…in a manger laid,” stanzas 3–4) and a cosmic doxology that weds worship to ethics (“All glory be to God on high, / and to the earth be peace…goodwill,” stanza 6). The hymn’s enduring popularity is typically explained by (i) its lucid narrative, which makes the Christmas story immediately graspable for public singing, (ii) its common-meter simplicity that fits many tunes and invites communal participation, and (iii) its distinctive historical status as the only Christmas hymn traditionally said to have been authorised for Anglican worship at a time when metrical psalms dominated, giving it wide, repeated seasonal use across generations.

Text: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

1 While shepherds watched their flocks by night,

all seated on the ground,

an angel of the Lord came down,

and glory shone around.

2 “Fear not,” said he for mighty dread

had seized their troubled mind

“glad tidings of great joy I bring

to you and all mankind.

3 “To you, in David’s town, this day

is born of David’s line

a Savior, who is Christ the Lord;

and this shall be the sign:

4 “The heavenly babe you there shall find

to human view displayed,

all simply wrapped in swaddling clothes

and in a manger laid.”

5 Thus spoke the angel. Suddenly

appeared a shining throng

of angels praising God, who thus

addressed their joyful song:

6 “All glory be to God on high,

and to the earth be peace;

to those on whom his favor rests

goodwill shall never cease.”

Psalter Hymnal, 1987

Annotations: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

| Stanza | Text (one stanza in one cell) | Annotation | Literary devices |

| 1 | While shepherds watched their flocks by night, all seated on the ground, an angel of the Lord came down, and glory shone around. | Establishes a quiet nocturnal pastoral setting, then interrupts it with divine descent and radiant “glory,” framing the Nativity as revelation breaking into ordinary life. | 🌙 Setting & atmosphere; 🖼️ Imagery; 📖 Biblical allusion; ⚖️ Heaven→earth contrast; ✨ Light/glory symbolism; 🎶 End-rhyme & hymn cadence |

| 2 | “Fear not,” said he for mighty dread had seized their troubled mind “glad tidings of great joy I bring to you and all mankind. | Moves from fear to reassurance, then to proclamation of “good news,” widening the audience from shepherds to all humanity—an emotional and theological expansion. | 🗣️ Direct speech; 👤 Personification (“dread…seized”); ⚖️ Fear vs. joy contrast; 📖 Biblical diction/allusion; 🔤 Sound patterning; 🎶 End-rhyme (mind/mankind) |

| 3 | “To you, in David’s town, this day is born of David’s line a Savior, who is Christ the Lord; and this shall be the sign: | Anchors the event in sacred time/place and Davidic lineage; intensifies identity through stacked titles, then introduces a “sign” that creates expectancy. | 🔁 Repetition/anaphora (“To you”); 📖 Biblical allusion (David/Bethlehem, lineage); 👑 Epithets/titles; ⏱️ “this day” immediacy; 🔮 Foreshadowing (“sign”); 🎶 Hymn cadence |

| 4 | “The heavenly babe you there shall find to human view displayed, all simply wrapped in swaddling clothes and in a manger laid.” | Specifies the “sign” as humility: the paradox of the “heavenly” shown in ordinary infant vulnerability—swaddling and a manger—making lowliness the proof of the divine. | ⚖️ Paradox (heavenly babe); 🖼️ Concrete imagery; ✨ Symbolism (manger/humility; incarnation); 📖 Biblical allusion; 🗣️ Direct speech; 🎶 End-rhyme (displayed/laid) |

| 5 | Thus spoke the angel. Suddenly appeared a shining throng of angels praising God, who thus addressed their joyful song: | Shifts from single messenger to a multitude; “Suddenly” accelerates pacing, while “shining throng” amplifies awe and turns the scene into communal worship. | ⏱️ Temporal shift/pacing (“Suddenly”); 🖼️ Imagery; ✨ Light symbolism; 📖 Biblical allusion; 🎶 Choral turn / hymn structure |

| 6 | “All glory be to God on high, and to the earth be peace; to those on whom his favor rests goodwill shall never cease.” | Concludes with doxology and blessing: heavenward glory paired with earthly peace; “favor” grounds the promise, and “never cease” provides emphatic closure. | 🗣️ Direct speech; 📖 Biblical allusion (angelic hymn); ⚖️ High/earth parallelism; ✨ Symbolism/themes (peace, goodwill); 🎶 End-rhyme (peace/cease) & refrain-like cadence; 🔤 Sound patterning |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

| Device (A–Z) | Short definition | Example from the hymn | Explanation (how it functions here) |

| 🔴 Alliteration | Repetition of initial consonant sounds | “glad tidings of great joy” | The repeated initial sounds support musicality and memorability, reinforcing the celebratory message. |

| 🟠 Allusion (Biblical) | Reference to a well-known text/story | “in David’s town…a Savior…Christ the Lord” | Echoes Luke’s Nativity account, grounding the hymn’s authority in scripture and tradition. |

| 🟡 Anaphora | Repetition at the start of successive units | “To you… / To you” | Personalizes the proclamation and intensifies direct address to the hearers. |

| 🟢 Assonance | Repetition of vowel sounds | “glory shone around” | The long “o” sounds produce a smooth, luminous sonic effect matching “glory.” |

| 🔵 Caesura | A meaningful pause within a line | “Fear not,” said he | The comma creates a dramatic pause, heightening reassurance after “mighty dread.” |

| 🟣 Consonance | Repetition of consonant sounds within/at ends of words | “mighty dread / had seized their troubled mind” | The repeated hard consonants intensify tension, mirroring fear before relief arrives. |

| 🟤 Contrast / Juxtaposition | Placing opposites side-by-side for effect | “heavenly babe… / …in a manger laid” | Highlights the Incarnation paradox: divine majesty revealed through humble circumstances. |

| ⚫ Dialogue | Direct speech in the poem/hymn | “ ‘Fear not,’ said he…” | Makes the narrative immediate and dramatic, as if the congregation overhears the angel. |

| 🟥 Diction (Elevated vs. Plain) | Word choice shaping tone and meaning | “Savior…Christ the Lord” vs. “swaddling clothes…manger” | Sacred titles convey holiness; plain domestic nouns emphasize humility—together creating theological depth. |

| 🟧 End Rhyme | Rhymes at line endings | “ground / around,” “mind / mankind” | Strengthens singability and recall; rhymes also link paired ideas across lines. |

| 🟨 End-Stopped Lines | Lines concluding with punctuation/complete sense | “all seated on the ground,” | Produces clarity and steadiness, supporting congregational comprehension and performance. |

| 🟩 Exclamation (Doxological Burst) | Emphatic praise language | “All glory be to God on high” | Shifts from narration to worship, inviting communal proclamation rather than private reflection. |

| 🟦 Imagery (Visual) | Sensory language creating a picture | “an angel…came down, / and glory shone around” | Vividly portrays the night scene transformed by radiance, heightening wonder and sacred atmosphere. |

| 🟪 Imperative Mood | Command/request language | “Fear not” | Functions pastorally: it addresses fear directly and models the move from dread to trust. |

| 🟫 Meter (Common Meter / Ballad Meter) | Regular rhythmic pattern (often 8.6.8.6) | “While shepherds watched their flocks by night” | Predictable rhythm enables easy singing and adaptation to multiple tunes, aiding popularity. |

| ⬛ Parallelism | Balanced grammatical structures | “All glory… / and to the earth be peace” | Joins worship (God) and ethics (peace), underscoring the hymn’s theological-social message. |

| 🟥 Repetition | Reuse of key words/phrases | “angel(s)” appears repeatedly | Reinforces the heavenly witness motif and sustains the tone of proclamation and praise. |

| 🟧 Symbolism | Concrete details signifying larger meanings | “manger” / “swaddling clothes” | Symbolize humility and accessibility: the divine is located among ordinary human realities. |

| 🟨 Tone Shift (Fear → Joy) | Movement in emotional attitude | “mighty dread” → “glad tidings…great joy” | The emotional arc enacts the hymn’s spiritual message: anxiety is replaced by assurance and celebration. |

| 🟩 Universal Address | Framing the message as for everyone | “to you and all mankind” | Establishes inclusivity, expanding the Nativity from a local scene to a universal proclamation. |

Themes: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

- 🔴 Incarnation and Divine Humility: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate frames the Nativity as a deliberate inversion of worldly expectations, because the announcement of cosmic significance is paired with the “sign” of radical simplicity, thereby insisting that divine authority is disclosed not through spectacle but through abasement. The hymn’s narrative logic moves from celestial radiance—“glory shone around”—to the startlingly ordinary details of embodiment, “wrapped in swaddling clothes” and “in a manger laid,” so that the listener is led to read poverty and vulnerability as theological meaning rather than incidental setting. By yoking “a Savior, who is Christ the Lord” to the lowly manger, Tate encodes the paradox of Christian doctrine, namely that transcendence enters history through dependence, and that salvation arrives by sharing the conditions of those it redeems. Consequently, the hymn does not merely recount an event; it interprets it, guiding congregational imagination toward a spirituality of humility.

- 🟠 Fear, Consolation, and Pastoral Reassurance: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate dramatizes the psychology of revelation by foregrounding fear as the first human response to the holy, yet it promptly converts dread into stability through the angel’s authoritative speech, “Fear not,” which functions simultaneously as command, comfort, and theological reframing. The shepherds’ “mighty dread” is not mocked or minimized; rather, it is acknowledged as a credible disturbance when “glory shone around,” and this admission lends emotional realism to the hymn’s devotional purpose. However, the angel’s intervention redirects the troubled mind from self-protective panic to receptive attention, because “glad tidings of great joy” is presented as news that answers fear with meaning, not with mere sentiment. In this way, the hymn becomes pastoral discourse in poetic form: it rehearses how anxiety is met by divine address, how terror yields to trust, and how the sacred draws near not to crush the vulnerable but to console them into hope.

- 🟡 Universal Salvation and Inclusive Proclamation: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate repeatedly expands the radius of the Nativity message, so that what begins as an encounter on a quiet night becomes a public declaration “to you and all mankind,” thereby establishing universality as a core theological and rhetorical principle. The hymn’s insistence on shared address matters because the shepherds, socially ordinary and religiously unremarkable, are made the first recipients of the announcement, which implies that access to grace is not restricted by status, learning, or power. Moreover, the phrase “glad tidings of great joy” is coupled with the explicit inclusiveness of “all mankind,” producing a logic in which joy is not private consolation but communal possibility, intended to cross boundaries of class and nation. When the Savior is named—“Christ the Lord”—the title carries doctrinal weight, yet the communicative posture remains open, because the message is framed as gift rather than gatekeeping. Thus, Tate’s hymn popularizes the Nativity not only by narrating it clearly, but by construing it as universally relevant, ethically expansive, and spiritually available to any hearer.

- 🟢 Heavenly Worship and Earthly Peace: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate culminates in the angelic chorus that translates revelation into liturgy—“All glory be to God on high”—while simultaneously binding worship to social consequence, since the same song announces “to the earth be peace” and enduring “goodwill.” The structure is significant: once the birth is proclaimed and the “sign” is given, a “shining throng” appears, so that the hymn’s narrative shifts from information to adoration, and from individual astonishment to collective praise. Yet Tate does not allow praise to remain purely vertical; instead, the doxology turns outward, presenting peace and goodwill as the earthward extension of heavenly glory, which means that true devotion must have ethical and communal traction. In practical terms, this closing vision supplies the hymn’s seasonal appeal, because it offers a concise theology of Christmas: God is glorified, the world is invited into reconciliation, and divine “favor” is imagined as a stabilizing force that “shall never cease.” Accordingly, the hymn’s popularity is inseparable from its capacity to unify doctrine, worship, and moral aspiration in a single singable climax.

Literary Theories and “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

| Literary theory | Poem-based references (quoted phrases) | How the theory reads the poem (concise) |

| ✝️📜 New Historicism / Cultural Poetics | “While shepherds watched their flocks by night”; “in David’s town”; “glad tidings… to you and all mankind” | Treats the hymn as a cultural text that circulates authority and belief: it embeds a biblical scene in a singable, communal form, shaping collective memory and religious identity through repeated performance. |

| 🧠🗣️ Reader-Response (Reception Theory) | “Fear not”; “mighty dread had seized their troubled mind”; “great joy”; “peace”; “goodwill shall never cease” | Focuses on how the hymn guides audience feeling: it scripts a movement from anxiety to consolation and assurance, inviting singers/readers to experience the transition as their own—fear → joy → peace. |

| 🧩🔍 Structuralism / Narratology | Sequence markers and scene shifts: “Thus spoke the angel. Suddenly”; the announced “sign”; chorus-like close: “All glory be to God on high” | Analyzes the hymn as a compact narrative with functions: (1) setting, (2) disruption (angel), (3) message, (4) verification (“sign”), (5) escalation (throng), (6) communal resolution (doxology). Meaning emerges from this patterned structure and binary oppositions (heaven/earth; fear/joy). |

| 🕊️✨ Myth/Archetypal Criticism (Jung/Campbell line) | “angel… came down”; “glory shone around”; “heavenly babe”; “peace”; “goodwill” | Reads the poem as a mythic pattern of “descent of the sacred”: the messenger/numinous light signals transformation; the humble child embodies the “divine in the ordinary,” and the ending offers archetypal restoration—cosmic harmony expressed as peace on earth. |

Critical Questions about “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

- 🔴 Critical Question 1: How does the hymn reshape the biblical Nativity narrative into a congregational argument about revelation and meaning?

“While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate condenses Luke’s Nativity into a sequence of theatrical “beats” that are designed less for textual fidelity than for communal intelligibility, because the poem selects a few high-yield moments—descent, dread, announcement, sign, and chorus—and turns them into a singable logic of faith. The opening image, “an angel of the Lord came down, / and glory shone around,” creates an atmosphere of interruption, while the shepherds’ “mighty dread” supplies psychological realism that prepares for the corrective imperative, “Fear not.” Tate then universalizes the event through “glad tidings of great joy…to you and all mankind,” shifting the scene from local history to inclusive proclamation. Finally, the “sign” of the “manger” and “swaddling clothes” interprets revelation as humility, so that the hymn argues, implicitly, that God is known through simplicity rather than grandeur. - 🟠 Critical Question 2: In what ways do meter, rhyme, and plain diction contribute to the hymn’s theological accessibility and enduring reception?

“While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate uses regular rhythm and predictable end rhyme (“ground/around,” “mind/mankind”) to make doctrine cognitively easy to retain and socially easy to perform, because a congregation can anticipate the line’s landing even before the sense fully resolves. This formal stability matters theologically: when the poem asserts “a Savior, who is Christ the Lord,” the elevated title is buffered by a familiar musical container, so that complex Christological claims arrive as common speech rather than specialist discourse. Likewise, plain nouns—“swaddling clothes,” “manger”—anchor abstraction in the domestic world, which encourages identification rather than distance. Even the narrative pivots are arranged for vocal clarity: the quotation marks and the brief command “Fear not” behave like stage directions, helping singers “hear” the scene. In effect, form does not merely decorate meaning; it operationalizes it, translating sacred content into repeatable, embodied practice. - 🟡 Critical Question 3: What does the hymn suggest about the human response to the divine, and how does it manage the movement from fear to joy?

“While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate presents fear not as moral failure but as a reasonable response to transcendence, since “mighty dread had seized their troubled mind” follows immediately after the irruptive brightness of “glory shone around.” Yet the poem refuses to let dread become the last interpretive frame, because the angel’s speech performs a reorientation: “Fear not” does not erase fear by denial; it addresses it by replacing uncertainty with intelligible promise, namely “glad tidings of great joy.” The grammar of direct address—“To you…this day”—intensifies intimacy, so that consolation is not abstract but personally targeted, and the concrete “sign” (the “heavenly babe…in a manger laid”) stabilizes belief by offering something verifiable within human perception. The result is an emotional pedagogy: fear is acknowledged, instructed, and finally absorbed into communal praise, culminating in the “joyful song” of the angels. - 🟢 Critical Question 4: How does the hymn’s final doxology connect worship to ethics, and what social vision does it implicitly promote?

“While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate ends by binding vertical devotion to horizontal responsibility, because the angels’ anthem—“All glory be to God on high, / and to the earth be peace”—treats praise and peace as a coupled pair rather than competing aims. This coupling matters critically: the hymn does not portray peace as a merely political settlement or an emotional mood, but as the earthward consequence of divine favor, since “goodwill shall never cease” is grounded “to those on whom his favor rests.” In that sense, the poem carries a social ethic without explicit social commentary; it proposes that communities shaped by the Nativity should be communities oriented toward reconciliation, restraint, and benevolence. Moreover, by giving this ethic to a “shining throng” rather than to rulers or institutions, Tate implies that the moral vision is not the property of elites; it is a public mandate sung over ordinary listeners, inviting them to embody what they celebrate.

Literary Works Similar to “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

- 🎄✨ “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity” by John Milton — Like Tate’s hymn, it frames the Nativity as a cosmic event where heaven’s intervention transforms the earthly night into a moment of sacred revelation and praise.

- 🌟🕊️ “In the Bleak Midwinter” by Christina Rossetti — Similar in devotional tone, it centers the paradox of divine majesty in humble circumstance, aligning closely with Tate’s “heavenly babe” and manger humility.

- 🌙🐑 “The Oxen” by Thomas Hardy — Echoes Tate’s pastoral Nativity atmosphere by returning to stable imagery and rural belief, treating Christmas night as a space where wonder and tradition press against doubt.

- 🔔🕯️ “Christmas Bells” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow — Comparable in its movement from distress to reassurance, it culminates in a moral-spiritual affirmation akin to Tate’s closing promise of “peace” and enduring “goodwill.”

Representative Quotations of “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

| Quotation | Context in the hymn | Theoretical perspective |

| 🔴 “While shepherds watched their flocks by night” | Establishes the ordinary nighttime vigil of working shepherds before the divine interruption. | New Historicism: The opening locates sacred meaning within a recognizable laboring context, suggesting that religious experience is embedded in social routines and material life rather than abstracted from them. |

| 🟠 “an angel of the Lord came down” | The decisive narrative turn: a heavenly messenger enters the human scene. | Narratology: This is the inciting incident that shifts the story from pastoral realism to revelation, introducing a supernatural agent who propels plot, authority, and interpretation. |

| 🟡 “and glory shone around” | Visual atmosphere of epiphany; the scene becomes radiant and overwhelming. | Phenomenology of Religion: The line represents the felt “appearance” of the sacred—an encounter that exceeds normal perception, generating awe, disruption, and transformed awareness. |

| 🟢 “Fear not,” | The angel’s first act is pastoral reassurance that directly addresses human panic. | Psychoanalytic Criticism: The command manages anxiety produced by the uncanny; it contains dread by offering symbolic order (a message, a meaning, a promise) that stabilizes the “troubled mind.” |

| 🔵 “glad tidings of great joy…to you and all mankind.” | The announcement expands from the shepherds to universal humanity. | Reader-Response Criticism: The inclusive address positions every listener as an implied recipient, producing identification and emotional participation, which helps explain the hymn’s persistent congregational appeal. |

| 🟣 “in David’s town, this day” | Pins the miracle to a specific place and an urgent present tense (“this day”). | Historical Theology: The line fuses prophecy and immediacy—messianic lineage (“David”) meets the “now” of salvation history, making doctrine feel temporally present rather than distant. |

| 🟤 “a Savior, who is Christ the Lord” | The hymn names the child with densely loaded titles that carry doctrinal authority. | Theological Criticism: Tate compresses Christology into a single clause, asserting identity (Savior), office (Christ/Messiah), and sovereignty (Lord), thereby turning narrative into confession. |

| ⚫ “The heavenly babe…all simply wrapped in swaddling clothes” | The “sign” emphasizes vulnerability and ordinariness rather than spectacle. | Ethical Criticism: The hymn’s moral imagination valorizes humility and simplicity; divinity is revealed through lowliness, implicitly critiquing prestige-based models of worth and power. |

| 🟥 “and in a manger laid.” | The climax of humility: the infant is placed in an animal feeding-trough. | Marxist Criticism: The manger becomes a material sign of poverty and marginality, framing salvation as arriving from outside elite spaces and challenging assumptions that the “important” must appear in privileged sites. |

| 🟧 “All glory be to God on high, and to the earth be peace” | The angelic chorus shifts narration into liturgy and links worship with social consequence. | Political Theology: The coupling of “glory” and “peace” implies that true devotion has public implications—praise is incomplete if it does not translate into reconciliation, goodwill, and communal ethics. |

Suggested Readings: “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks” by Nahum Tate

Books

- Dearmer, Percy, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Martin Shaw, editors. The Oxford Book of Carols. Oxford UP, 1928.

- Bailey, Albert Edward. The Gospel in Hymns: Backgrounds and Interpretations. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950.

Academic Articles

- Russell, Ian. “’While Shepherds Watched their Flocks by Night’: A Paradigm of English Village Carolling for Three Centuries.” European Journal of Musicology, vol. 20, no. 1, 2022, pp. 81–104. https://bop.unibe.ch/EJM/article/view/8341. Accessed 12 Jan. 2026. (DOI: https://doi.org/10.5450/EJM.20.1.2021.81.)

- Temperley, Nicholas. “Kindred and Affinity in Hymn Tunes.” The Musical Times, vol. 113, no. 1555, Sept. 1972, pp. 905–909. PDF, https://hymnologyarchive.squarespace.com/s/Temperley-Affinity-MT-1972.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan. 2026.

Poem / Text Websites

- Tate, Nahum. “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks.” Hymnary.org, https://hymnary.org/text/while_shepherds_watched_their_flocks_by. Accessed 12 Jan. 2026.

- Tate, Nahum. “While Shepherds Watch’d Their Flocks by Night.” Poem of the Week, https://www.potw.org/archive/potw323.html. Accessed 12 Jan. 2026.