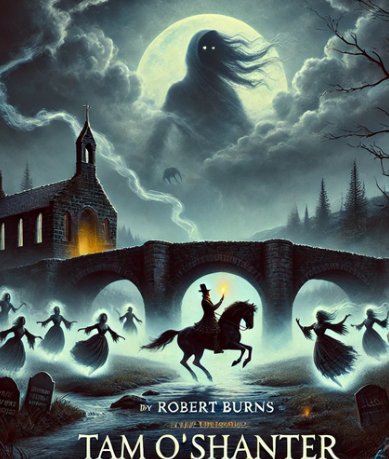

Introduction: “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

“Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns, first appeared in 1791 in the collection Gavin Hamilton’s Edition of Burns’s Poems, was set in the Scottish countryside. It masterfully blends humor, the supernatural, and moral reflection, making it a staple in literary anthologies and textbooks. It tells the tale of Tam, a habitual drunkard whose escapades lead him to witness a wild witch’s dance at the haunted Kirk Alloway, culminating in a dramatic chase. Its popularity stems from its vivid imagery, engaging rhythm, and relatable moral on indulgence and consequences. Memorable lines like “But pleasures are like poppies spread” and “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious” showcase Burns’s poetic dexterity and his deep engagement with human folly and resilience. The poem’s humor, combined with its exploration of Scottish folklore, continues to captivate students and readers, enriching its legacy in literary studies.

Text: “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

When chapman billies leave the street,

And drouthy neebors neebors meet,

As market-days are wearing late,

And folk begin to tak the gate;

While we sit bousin, at the nappy,

And gettin fou and unco happy,

We think na on the lang Scots miles,

The mosses, waters, slaps, and stiles,

That lie between us and our hame,

Whare sits our sulky, sullen dame,

Gathering her brows like gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

This truth fand honest Tam o’ Shanter,

As he frae Ayr ae night did canter:

(Auld Ayr, wham ne’er a town surpasses,

For honest men and bonie lasses.)

O Tam! had’st thou but been sae wise

As taen thy ain wife Kate’s advice!

She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum,

A bletherin, blusterin, drunken blellum;

That frae November till October,

Ae market-day thou was na sober;

That ilka melder wi’ the miller,

Thou sat as lang as thou had siller;

That ev’ry naig was ca’d a shoe on,

The smith and thee gat roarin fou on;

That at the Lord’s house, ev’n on Sunday,

Thou drank wi’ Kirkton Jean till Monday.

She prophesied, that, late or soon,

Thou would be found deep drown’d in Doon;

Ot catch’d wi’ warlocks in the mirk,

By Alloway’s auld haunted kirk.

Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet,

To think how mony counsels sweet,

How mony lengthen’d sage advices,

The husband frae the wife despises!

But to our tale:—Ae market night,

Tam had got planted unco right,

Fast by an ingle, bleezing finely,

Wi’ reaming swats that drank divinely;

And at his elbow, Souter Johnie,

His ancient, trusty, drouthy crony:

Tam lo’ed him like a vera brither;

They had been fou for weeks thegither.

The night drave on wi’ sangs and clatter;

And ay the ale was growing better:

The landlady and Tam grew gracious

Wi’ secret favours, sweet, and precious:

The souter tauld his queerest stories;

The landlord’s laugh was ready chorus:

The storm without might rair and rustle,

Tam did na mind the storm a whistle.

Care, mad to see a man sae happy,

E’en drown’d himsel amang the nappy:

As bees flee hame wi’ lades o’ treasure,

The minutes wing’d their way wi’ pleasure;

Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious,

O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white—then melts forever;

Or like the borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.

Nae man can tether time or tide:

The hour approaches Tam maun ride,—

That hour, o’ night’s black arch the key-stane

That dreary hour he mounts his beast in;

And sic a night he taks the road in,

As ne’er poor sinner was abroad in.

The wind blew as ‘twad blawn its last;

The rattling show’rs rose on the blast;

The speedy gleams the darkness swallow’d;

Loud, deep, and lang the thunder bellow’d:

That night, a child might understand,

The Deil had business on his hand.

Weel mounted on his grey mare, Meg,—

A better never lifted leg,—

Tam skelpit on thro’ dub and mire,

Despising wind and rain and fire;

Whiles holding fast his guid blue bonnet,

Whiles crooning o’er some auld Scots sonnet,

Whiles glowrin round wi’ prudent cares,

Lest bogles catch him unawares.

Kirk-Alloway was drawing nigh,

Whare ghaists and houlets nightly cry.

By this time he was cross the ford,

Whare in the snaw the chapman smoor’d;

And past the birks and meikle stane,

Whare drucken Charlie brak’s neckbane:

And thro’ the whins, and by the cairn,

Whare hunters fand the murder’d bairn;

And near the thorn, aboon the well,

Whare Mungo’s mither hang’d hersel.

Before him Doon pours all his floods;

The doubling storm roars thro’ the woods;

The lightnings flash from pole to pole,

Near and more near the thunders roll;

When, glimmering thro’ the groaning trees,

Kirk-Alloway seem’d in a bleeze:

Thro’ ilka bore the beams were glancing,

And loud resounded mirth and dancing.

Inspiring bold John Barleycorn!

What dangers thou can’st make us scorn!

Wi’ tippenny we fear nae evil;

Wi’ usquebae we’ll face the devil!

The swats sae ream’d in Tammie’s noddle,

Fair play, he car’d na deils a boddle.

But Maggie stood right sair astonish’d,

Till, by the heel and hand admonish’d,

She ventur’d forward on the light;

And, wow! Tam saw an unco sight!

Warlocks and witches in a dance;

Nae cotillion brent-new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels

Put life and mettle in their heels.

A winnock bunker in the east,

There sat Auld Nick in shape o’ beast:

A towzie tyke, black, grim, and large,

To gie them music was his charge;

He screw’d the pipes and gart them skirl,

Till roof and rafters a’ did dirl.—

Coffins stood round like open presses,

That shaw’d the dead in their last dresses;

And by some devilish cantraip sleight

Each in its cauld hand held a light,

By which heroic Tam was able

To note upon the haly table

A murderer’s banes in gibbet airns;

Twa span-lang, wee, unchristen’d bairns;

A thief, new-cutted frae the rape—

Wi’ his last gasp his gab did gape;

Five tomahawks, wi’ blude red-rusted;

Five scimitars, wi’ murder crusted;

A garter, which a babe had strangled;

A knife, a father’s throat had mangled,

Whom his ain son o’ life bereft—

The grey hairs yet stack to the heft;

Wi’ mair o’ horrible and awfu’,

Which ev’n to name wad be unlawfu’.

As Tammie glowr’d, amaz’d and curious,

The mirth and fun grew fast and furious:

The piper loud and louder blew,

The dancers quick and quicker flew;

They reel’d, they set, they cross’d, they cleekit

Till ilka carlin swat and reekit

And coost her duddies to the wark

And linket at it in her sark!

Now Tam, O Tam! had thae been queans,

A’ plump and strapping in their teens!

Their sarks, instead o’ creeshie flannen,

Been snaw-white seventeen hunder linen!—

Thir breeks o’ mine, my only pair,

That ance were plush, o’ gude blue hair,

I wad hae gien them aff y hurdies,

For ae blink o’ the bonie burdies!

But wither’d beldams, auld and droll,

Rigwoodie hags wad spean a foal,

Lowping and flinging on a crummock.

I wonder didna turn thy stomach.

But Tam ken’d what was what fu’ brawlie;

There was ae winsom wench and walie,

That night enlisted in the core

(Lang after ken’d on Carrick shore.

For mony a beast to dead she shot,

And perish’d mony a bonie boat,

And shook baith meikle corn and bear,

And kept the country-side in fear);

Her cutty sark o’ Paisley harn,

That while a lassie she had worn,

In longitude tho’ sorely scanty,

It was her best, and she was vauntie.

Ah! little ken’d thy reverend grannie,

That sark she coft for her wee Nannie,

Wi’ twa pund Scots (’twas a’ her riches),

Wad ever grac’d a dance of witches!

But here my Muse her wing maun cow’r,

Sic flights are far beyond her pow’r;

To sing how Nannie lap and flang,

(A souple jad she was and strang),

And how Tam stood like ane bewitch’d,

And thought his very een enrich’d;

Even Satan glowr’d and fidg’d fu’ fain,

And hotch’d and blew wi’ might and main:

Till first ae caper, syne anither,

Tam tint his reason a’ thegither,

And roars out, “Weel done, Cutty-sark!”

And in an instant all was dark:

And scarcely had he Maggie rallied,

When out the hellish legion sallied.

As bees bizz out wi’ angry fyke,

When plundering herds assail their byke;

As open pussie’s mortal foes,

When, pop! she starts before their nose;

As eager runs the market-crowd,

When “Catch the thief!” resounds aloud;

So Maggie runs, the witches follow,

Wi’ mony an eldritch skriech and hollo.

Ah, Tam! ah, Tam! thou’ll get thy fairin!

In hell they’ll roast thee like a herrin!

In vain thy Kate awaits thy comin!

Kate soon will be a woefu’ woman!

Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg,

And win the key-stane of the brig:

There at them thou thy tail may toss,

A running stream they dare na cross.

But ere the key-stane she could make,

The fient a tail she had to shake!

For Nannie far before the rest,

Hard upon noble Maggie prest,

And flew at Tam wi’ furious ettle;

But little wist she Maggie’s mettle—

Ae spring brought aff her master hale

But left behind her ain grey tail:

The carlin claught her by the rump,

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

Now, wha this tale o’ truth shall read,

Ilk man and mother’s son, take heed,

Whene’er to drink you are inclin’d,

Or cutty-sarks run in your mind,

Think, ye may buy the joys o’er dear,

Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mear.

Annotations: “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

| Stanza | Annotation |

| Opening lines: When chapman billies leave the street… | Sets the scene with an idyllic yet ominous tone. Burns describes the conviviality of market day and the carefree drinking of Tam and his companions, contrasting it with the long and challenging journey home, reflecting the themes of recklessness and forewarning. |

| This truth fand honest Tam o’ Shanter… | Introduces Tam as a relatable, flawed protagonist. Burns humorously portrays Tam’s shortcomings through his wife’s warnings and highlights his fondness for drink, setting the stage for the supernatural events. |

| Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet… | A reflective pause where the narrator sympathizes with the wives who are often ignored by their husbands. It adds a moralistic tone, emphasizing Tam’s folly in disregarding his wife’s advice. |

| But to our tale:—Ae market night… | The narrative begins in earnest with a vivid description of Tam’s drunken escapades and camaraderie with his friend Souter Johnnie. This stanza establishes the carefree yet foreboding atmosphere. |

| Care, mad to see a man sae happy… | A philosophical observation about the fleeting nature of happiness, setting a somber tone before the impending chaos. Burns uses rich imagery to depict the inevitability of time and consequence. |

| The wind blew as ‘twad blawn its last… | Describes the ominous weather as Tam embarks on his journey home. The stormy night mirrors the supernatural elements Tam is about to encounter, building suspense and atmosphere. |

| Weel mounted on his grey mare, Meg… | Introduces Tam’s loyal mare, Meg, and emphasizes Tam’s bravery and recklessness as he ventures into the dark. His prudence contrasts with his earlier frivolity, showing a shift in mood. |

| Kirk-Alloway was drawing nigh… | The description of haunted locales builds suspense. Each site is linked with a gruesome backstory, reflecting Scottish folklore and setting the eerie tone for the encounter at the kirk. |

| Inspiring bold John Barleycorn!… | Tam’s intoxication emboldens him, dismissing fear as he approaches the supernatural. Burns humorously attributes Tam’s courage to the effects of alcohol, illustrating his flawed heroism. |

| Warlocks and witches in a dance… | A vivid, surreal depiction of witches and the devil dancing in Kirk-Alloway. Burns uses grotesque imagery and humor to capture Tam’s amazement and terror, heightening the drama. |

| But Tam ken’d what was what fu’ brawlie… | Introduces the memorable “cutty sark” (short shirt) worn by Nannie, a witch. The humorous and sensual imagery contrasts with the ominous scene, reflecting Tam’s flawed focus on appearances despite the danger. |

| But here my Muse her wing maun cow’r… | The climax of the dance scene, where Tam foolishly cheers on Nannie, draws the attention of the witches. Burns shifts the tone from admiration to impending danger as the chase begins. |

| As bees bizz out wi’ angry fyke… | A frantic description of the witches chasing Tam, comparing their fury to swarming bees. The vivid imagery captures the urgency and terror of the pursuit. |

| Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg… | The chase reaches its climax as Meg races toward the safety of the bridge. Burns incorporates Scottish folklore, noting that witches cannot cross running water, adding tension and cultural context. |

| But ere the key-stane she could make… | A dramatic and humorous resolution as Meg saves Tam by reaching the bridge but loses her tail to the pursuing witch. This scene highlights Tam’s narrow escape and the consequences of his recklessness. |

| Now, wha this tale o’ truth shall read… | The moral of the poem warns readers about the perils of indulgence and folly. Burns humorously admonishes the audience to learn from Tam’s mistakes, reinforcing the poem’s didactic purpose. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

| Device | Example | Explanation |

| Alliteration | “There at them thou thy tail may toss” | The repetition of the “th” rhythm and musicality, emphasizing the subject’s trembling nature. |

| Allusion | “Auld Nick in shape o’ beast” | References the devil in Scottish folklore, enriching the poem with cultural and mythological depth. |

| Apostrophe | “O Tam! had’st thou but been sae wise…” | Directly addressing Tam involves the reader emotionally and creates a conversational tone. |

| Assonance | “The doubling storm roars thro’ the woods” | Repetition of the “o” vowel sound emphasizes the storm’s ominous intensity. |

| Couplet | “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious, / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” | Two consecutive rhyming lines emphasize Tam’s triumph, creating rhythm and memorability. |

| Dialect | “Whene’er to drink you are inclin’d” | Use of Scots dialect adds authenticity, grounding the poem in Burns’s cultural context. |

| Foreshadowing | “She prophesied, that, late or soon, / Thou would be found deep drown’d in Doon…” | Predicts the dangers Tam will face, creating suspense for the reader. |

| Hyperbole | “And loud resounded mirth and dancing” | Exaggeration emphasizes the supernatural chaos at Kirk-Alloway. |

| Imagery | “The lightnings flash from pole to pole, / Near and more near the thunders roll” | Vivid sensory descriptions enhance the poem’s dramatic atmosphere. |

| Irony | “Ah, Tam! ah, Tam! thou’ll get thy fairin! / In hell they’ll roast thee like a herrin!” | Dark humor contrasts with Tam’s serious predicament, creating situational irony. |

| Juxtaposition | “But pleasures are like poppies spread, / You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed” | Contrasts fleeting happiness with impending doom, emphasizing the transient nature of joy. |

| Metaphor | “As bees bizz out wi’ angry fyke” | Compares the witches’ pursuit to angry bees, emphasizing their relentless energy. |

| Mood | “The wind blew as ‘twad blawn its last; / The rattling show’rs rose on the blast” | Establishes an ominous and suspenseful mood that mirrors Tam’s predicament. |

| Onomatopoeia | “Till roof and rafters a’ did dirl” | The word “dirl” mimics the sound it describes, adding auditory realism. |

| Personification | “Care, mad to see a man sae happy, / E’en drown’d himsel amang the nappy” | Abstract concepts like “Care” are given human traits, emphasizing their pervasive impact on life. |

| Repetition | “Nae man can tether time or tide” | Repetition of “time” and “tide” underscores the inevitability of fate. |

| Rhyme | “Tam tint his reason a’ thegither, / And roars out, ‘Weel done, Cutty-sark!'” | The consistent rhyme enhances the poem’s rhythm and cohesion. |

| Simile | “But pleasures are like poppies spread” | A direct comparison emphasizes the fleeting nature of pleasures, reinforcing the poem’s moral. |

| Symbolism | “A running stream they dare na cross” | Represents safety and boundaries, rooted in Scottish folklore, between the natural and supernatural worlds. |

| Tone | “Now, wha this tale o’ truth shall read, / Ilk man and mother’s son, take heed” | The tone shifts from humorous to moralistic, guiding the reader to reflect on Tam’s behavior. |

Themes: “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

1. The Transience of Pleasure: One of the central themes of “Tam o’ Shanter” is the fleeting nature of human pleasure, as vividly captured in the lines, “But pleasures are like poppies spread, / You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed.” Burns compares moments of joy to delicate flowers, snowflakes, and rainbows—ephemeral beauties that disappear as quickly as they appear. This metaphor underscores the short-lived satisfaction of Tam’s indulgence in drink and revelry at the tavern. The camaraderie and drunken laughter shared with Souter Johnnie, described as “The night drave on wi’ sangs and clatter; / And ay the ale was growing better,” offer Tam temporary joy but ultimately lead him into the dangerous world of Kirk-Alloway. The theme serves as a poignant reminder of the consequences of hedonism, illustrating that fleeting pleasures often come at a significant cost.

2. The Supernatural and Folklore: The supernatural pervades “Tam o’ Shanter,” bringing to life the eerie and fantastical elements of Scottish folklore. Burns sets the stage for Tam’s encounter with the supernatural through chilling descriptions of the night: “The wind blew as ‘twad blawn its last; / The rattling show’rs rose on the blast.” The climax occurs at Kirk-Alloway, where Tam witnesses “Warlocks and witches in a dance; / Nae cotillion brent-new frae France,” grotesque figures reveling to the devil’s piping. The imagery of “coffins stood round like open presses, / That shaw’d the dead in their last dresses,” creates an unsettling and surreal atmosphere, immersing readers in the supernatural world. The witches’ pursuit, which mirrors folklore’s fascination with boundaries between the natural and otherworldly, adds both humor and terror to the tale, embodying the rich tradition of Scottish oral storytelling.

3. The Conflict Between Responsibility and Folly: Tam’s story is fundamentally one of a man torn between responsibility and folly, as highlighted in the narrator’s exclamation, “O Tam! had’st thou but been sae wise / As taen thy ain wife Kate’s advice!” Tam is warned repeatedly by his wife about the dangers of his drinking and irresponsibility: “She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum, / A bletherin, blusterin, drunken blellum.” However, Tam’s inability to resist temptation leads him to ignore her sage counsel, prioritizing his pleasures over prudence. This conflict drives the narrative, culminating in Tam’s harrowing escape from Kirk-Alloway. The poem humorously yet poignantly portrays the universal struggle between indulgence and duty, with the narrator lamenting, “Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet, / To think how mony counsels sweet / The husband frae the wife despises!” Through Tam’s character, Burns explores the enduring tension between personal desires and moral accountability.

4. The Power of Loyalty and Bravery: Despite Tam’s recklessness, his mare Maggie (Meg) emerges as a symbol of loyalty and bravery. As the witches pursue Tam, Burns writes, “Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg, / And win the key-stane of the brig.” Meg’s heroic sprint toward the bridge—the threshold separating Tam from danger—represents unwavering devotion in the face of chaos. The detail that witches cannot cross running water, a motif rooted in folklore, heightens the tension of the chase. Meg’s ultimate sacrifice, losing her tail to save Tam, is captured in the lines, “Ae spring brought aff her master hale, / But left behind her ain grey tail.” Her steadfastness contrasts with Tam’s irresponsibility, serving as a redemptive force in the narrative. Through Meg, Burns underscores the importance of courage and loyalty, even when human folly dominates the story.

Literary Theories and “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

| Literary Theory | Application to “Tam o’ Shanter” | References from the Poem |

| Formalism | This theory focuses on the structure, language, and literary devices in the poem. “Tam o’ Shanter” exemplifies intricate poetic techniques like alliteration, imagery, and rhythm to evoke a dynamic narrative. | Examples include the vivid imagery in “The lightnings flash from pole to pole, / Near and more near the thunders roll” and the rhythmic couplet, “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious, / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” |

| Psychoanalytic Criticism | Tam’s actions can be interpreted through Freudian ideas of the id, ego, and superego. His indulgence in drink and revelry reflects the id’s dominance, while his wife Kate symbolizes the superego, warning him of consequences. | Kate’s admonitions, “She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum, / A bletherin, blusterin, drunken blellum,” highlight the superego’s role, while Tam’s drunken revelry, “Care, mad to see a man sae happy,” reflects his pursuit of immediate gratification. |

| Cultural Criticism | This theory explores how the poem reflects 18th-century Scottish culture, particularly its folklore, dialect, and societal norms. Burns captures Scotland’s oral traditions and superstitions, such as the belief in witches and haunted places. | The depiction of the supernatural at Kirk-Alloway, “Warlocks and witches in a dance; / Nae cotillion brent-new frae France,” and the cultural importance of the Scots dialect throughout the poem, enriches its cultural significance. |

| Moral Criticism | The poem can be analyzed as a moral tale, warning readers against indulgence and recklessness. Tam’s actions lead to his near destruction, demonstrating the consequences of ignoring societal and personal responsibilities. | The narrator’s moralistic reflection, “Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet, / To think how mony counsels sweet / The husband frae the wife despises,” conveys a didactic tone, warning readers of the dangers of excess and irresponsibility. |

Critical Questions about “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

1. How does Burns use humor to balance the supernatural elements in “Tam o’ Shanter”?

Burns skillfully uses humor to provide relief and balance to the dark and eerie supernatural elements of the poem. The protagonist, Tam, is depicted as a flawed yet endearing character whose drunken escapades add a comedic tone. Lines such as “Ah, Tam! had’st thou but been sae wise / As taen thy ain wife Kate’s advice!” humorously highlight his inability to heed warnings, making his eventual predicament both alarming and amusing. Even amidst the witches’ chaotic dance, Tam’s reaction injects levity: “Weel done, Cutty-sark!” This exclamation not only angers the witches but also underscores his lack of judgment, evoking laughter despite the danger. The grotesque yet absurd imagery of the witches, such as “Nae cotillion brent-new frae France, / But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels,” adds to the comedic absurdity. Burns ensures that the supernatural remains entertaining, using humor to make the tale accessible and engaging while maintaining its underlying tension.

2. How does “Tam o’ Shanter” reflect themes of gender dynamics and societal expectations?

The poem portrays a complex interplay of gender roles and societal expectations, particularly through the relationship between Tam and his wife, Kate. Kate embodies the voice of reason and morality, warning Tam of the dangers of his behavior: “She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum, / A bletherin, blusterin, drunken blellum.” Her practical and critical perspective contrasts with Tam’s recklessness, reflecting traditional gender roles where women are tasked with upholding household stability. The narrator sympathizes with Kate, lamenting, “Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet, / To think how mony counsels sweet / The husband frae the wife despises!” Yet, the poem also humorously acknowledges the inevitability of Tam’s folly, suggesting a light-hearted critique of male irresponsibility. Through this dynamic, Burns explores broader societal themes, portraying women as guardians of morality while satirizing the often-dismissive attitudes of men toward their advice.

3. What role does folklore play in shaping the poem’s narrative and themes?

Scottish folklore is central to “Tam o’ Shanter,” both in its narrative structure and thematic depth. Burns weaves local legends and superstitions into the poem, particularly through the depiction of Kirk-Alloway and its inhabitants. The witches’ dance, described as “Warlocks and witches in a dance; / Nae cotillion brent-new frae France,” and the presence of the devil playing the bagpipes, anchor the story in supernatural folklore. The belief that witches cannot cross running water, referenced in “A running stream they dare na cross,” is a key plot device, highlighting the cultural significance of these myths. These elements enrich the poem’s narrative, offering both entertainment and a connection to Scotland’s oral storytelling tradition. Folklore also serves as a metaphor for human fears and moral lessons, reinforcing the idea that Tam’s recklessness and indulgence invite otherworldly consequences.

4. How does the poem explore the tension between freedom and consequence?

“Tam o’ Shanter” vividly captures the tension between the allure of freedom and the inevitability of consequence. Tam’s night of revelry at the tavern represents a moment of unrestrained freedom, described in celebratory terms: “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious, / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” However, this freedom comes at a cost, as Tam’s drunken state leads him into the perilous world of the supernatural. The witches’ chase serves as a metaphor for the consequences of his actions, with the narrator warning, “Think, ye may buy the joys o’er dear.” The contrast between Tam’s carefree indulgence and his frantic escape on Meg underscores the poem’s central moral: unbridled freedom often carries unforeseen dangers. Burns explores this theme with both humor and gravity, illustrating the universal human struggle to balance desire with responsibility.

Literary Works Similar to “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

- “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Similarity: Both poems blend the supernatural with moral lessons, using vivid imagery and suspenseful narratives to explore human folly and redemption. - “The Devil’s Thoughts” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Similarity: Both poems feature satirical depictions of the devil and supernatural themes, using humor and grotesque imagery to critique human behavior. - “Goblin Market” by Christina Rossetti

Similarity: This poem shares themes of temptation and consequences, with supernatural entities that challenge the protagonists’ moral resolve. - “The Erl-King” by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Similarity: Both poems involve a chase by supernatural beings, capturing a sense of foreboding and the danger of straying into the realm of the otherworldly.

Representative Quotations of “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “But pleasures are like poppies spread, / You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed.” | Reflects on the fleeting nature of joy during Tam’s night of indulgence. | Moral Criticism: Highlights the transient nature of pleasure and the consequences of hedonism. |

| “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious, / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” | Describes Tam’s drunken euphoria as he revels in his temporary freedom. | Psychoanalytic Criticism: Represents Tam’s id-driven pursuit of immediate gratification. |

| “Ah, Tam! had’st thou but been sae wise / As taen thy ain wife Kate’s advice!” | A lament for Tam’s reckless disregard for his wife’s warnings. | Feminist Criticism: Highlights gender dynamics, portraying Kate as the voice of reason dismissed by Tam. |

| “The wind blew as ‘twad blawn its last; / The rattling show’rs rose on the blast.” | Sets the ominous tone as Tam begins his journey home in stormy weather. | Formalism: Uses vivid imagery and auditory devices to establish a foreboding mood. |

| “Warlocks and witches in a dance; / Nae cotillion brent-new frae France.” | Describes the wild supernatural scene Tam encounters at Kirk-Alloway. | Cultural Criticism: References folklore and contrasts it humorously with European traditions. |

| “A running stream they dare na cross.” | Refers to the folkloric belief that witches cannot cross running water, symbolizing a boundary between safety and peril. | Structuralism: Examines the motif of the protective boundary as a recurring element in folklore. |

| “Weel done, Cutty-sark!” | Tam’s drunken exclamation during the witches’ dance, provoking their pursuit. | Postmodernism: Highlights the absurdity of Tam’s reaction to danger, blending humor with chaos. |

| “Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg, / And win the key-stane of the brig.” | Depicts Meg’s desperate race to the bridge to save Tam from the witches. | Humanism: Celebrates loyalty and bravery in the face of danger, as exemplified by Meg. |

| “Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet, / To think how mony counsels sweet / The husband frae the wife despises.” | Reflects on the recurring tendency of men to ignore women’s advice, often to their detriment. | Feminist Criticism: Critiques societal norms where women’s wisdom is undervalued. |

| “Think, ye may buy the joys o’er dear, / Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mear.” | Concludes the poem with a moralistic warning against indulgence. | Moral Criticism: Reinforces the consequences of recklessness with a direct lesson for the audience. |

Suggested Readings: “Tam o’ Shanter” by Robert Burns

- MacLAINE, ALLAN H. “Burns’s Use of Parody in ‘Tam O’Shanter.'” Criticism, vol. 1, no. 4, 1959, pp. 308–16. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23090932. Accessed 5 Jan. 2025.

- Noyes, Russell. “Wordsworth and Burns.” PMLA, vol. 59, no. 3, 1944, pp. 813–32. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/459386. Accessed 5 Jan. 2025.

- Burns, Robert, and Francis M. Collinson. Tam O’Shanter and Other Poems. WP Nimmo, Hay, & Mitchell, 1912.

- Weston, John C. “The Narrator of Tam o’ Shanter.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 8, no. 3, 1968, pp. 537–50. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/449618. Accessed 5 Jan. 2025.

- White, Kenneth. “‘Tam o’ Shanter’: A New Reading.” The Collected Works of Kenneth White, Volume 2: Mappings: Landscape, Mindscape, Wordscape, edited by Cairns Craig, Edinburgh University Press, 2021, pp. 46–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctv1kd7x1p.9. Accessed 5 Jan. 2025.