Introduction: “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

“The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché first appeared in 1978 in Women’s International Resource Exchange and was later collected in The Country Between Us (1978; published 1978–79, copyright 1981). Rooted in Forché’s eyewitness experience of state violence in El Salvador, the poem exposes the banality and theatricality of terror by juxtaposing domestic normalcy with atrocity: the civilized rituals of dinner, “rack of lamb, good wine,” and a parrot saying “hello” are shattered by the colonel’s sack of severed ears, which “came alive” in a water glass. Its central ideas include the routinization of political brutality, the collapse of moral language under authoritarian power (“As for the rights of anyone…”), and the ethical burden placed on poetry itself when violence demands testimony (“Something for your poetry, no?”). The poem’s enduring popularity stems from its stark documentary realism, its refusal of metaphor at the climactic moment (“There is no other way to say this”), and its chilling indictment of spectatorship, captured in the final image where “Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground,” suggesting that even mutilated bodies continue to listen for truth.

Text: “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

WHAT YOU HAVE HEARD is true. I was in his house. His wife carried

a tray of coffee and sugar. His daughter filed her nails, his son went

out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the

cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on its black cord over

the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English.

Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to

scoop the kneecaps from a man’s legs or cut his hands to lace. On

the windows there were gratings like those in liquor stores. We had

dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for

calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of

bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief

commercial in Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was

some talk then of how difficult it had become to govern. The parrot

said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed

himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say

nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries

home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like

dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one

of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water

glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As

for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck them-

selves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last

of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some

of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the

ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

May 1978

Copyright Credit: All lines from “The Colonel” from The Country Between Us by Carolyn Forché, Copyright (c) 1981 by Carolyn Forché. Originally appeared in Women’s International Resource Exchange. Used by Permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Additional territory: Virginia Barber, William Morris Agency, 1325 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10019

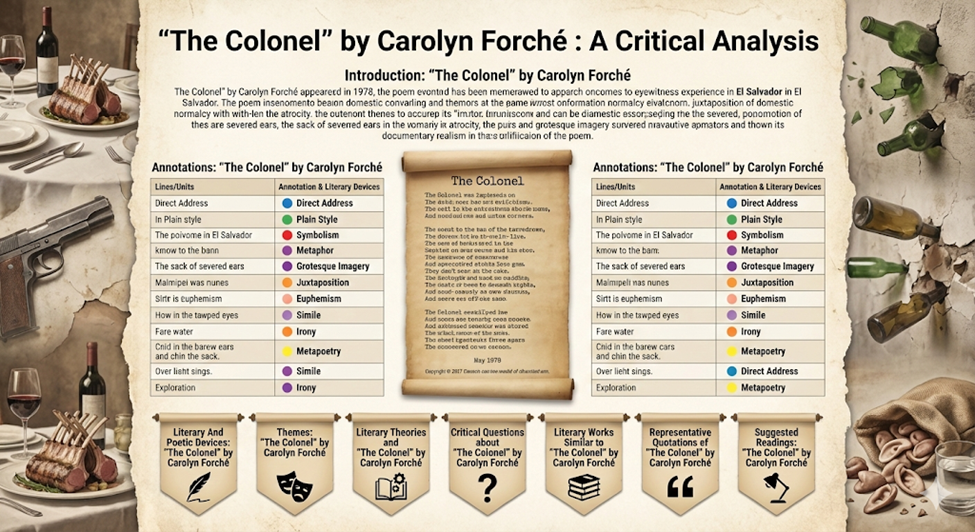

Annotations: “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

| Text (Line /Unit) | Annotation & Literary Devices |

| “WHAT YOU HAVE HEARD is true. I was in his house… a pistol on the cushion beside him.” | Establishes testimonial realism and credibility through direct witness. Domestic normalcy is juxtaposed with latent violence. 🔵 Direct Address – confronts reader as witness🟢 Plain Style / Documentary Tone – journalistic realism🔴 Juxtaposition – domestic calm vs. weaponized power🟣 Symbolism – pistol = normalized violence |

| “The moon swung bare on its black cord… It was in English.” | The moon becomes an image of exposure and surveillance; English-language television hints at U.S. cultural/political presence. 🟠 Metaphor – moon as hanging bulb / exposure🟡 Imagery – stark visual contrast🔵 Political Allusion – English TV = imperial reach |

| “Broken bottles were embedded in the walls… gratings like those in liquor stores.” | Architecture itself becomes a weapon; the house mirrors a prison or torture chamber. 🔴 Grotesque Imagery – bodily mutilation implied🟣 Metonymy – walls stand for state brutality🟢 Irony – domestic security becomes sadistic defense |

| “We had dinner, rack of lamb, good wine… green mangoes, salt, a type of bread.” | Ritualized hospitality contrasts violently with state terror; echoes biblical and sacrificial imagery. 🟠 Juxtaposition – luxury vs. cruelty🟡 Symbolism – lamb = sacrifice🔵 Cultural Irony – civility masking atrocity |

| “I was asked how I enjoyed the country… how difficult it had become to govern.” | Casual political discourse sanitizes repression; euphemism replaces violence. 🟢 Euphemism – “govern” conceals terror🔴 Dramatic Irony – reader knows the cost of governance🟣 Satire – bureaucratic language critiqued |

| “The parrot said hello… told it to shut up.” | The parrot symbolizes uncontrolled speech; its silencing mirrors political repression. 🟡 Symbolism – parrot = free speech🔵 Personification – animal voice politicized🔴 Allegory – censorship enacted |

| “He spilled many human ears on the table… like dried peach halves.” | The poem’s central horror: ears symbolize surveillance, testimony, and silenced victims. The simile intensifies shock through grotesque beauty. 🔴 Shock Imagery – visceral horror🟠 Simile – ears ≈ dried peaches🟣 Symbolism – ears = listening, dissent, memory |

| “It came alive there… tell your people they can go fuck themselves.” | The colonel openly rejects human rights discourse; the ear “coming alive” suggests memory and testimony persist. 🔵 Irony – life within death🔴 Blunt Diction – moral nihilism🟢 Political Invective – rejection of international ethics |

| “Something for your poetry, no?… pressed to the ground.” | Poetry is challenged to bear witness; the final image affirms that the oppressed still “listen” and remember. 🟣 Metapoetry – poetry as moral record🟡 Personification – ears listening after death🔵 Symbolic Closure – testimony survives terror |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

| Literary / Poetic Device | Example from the Poem | Explanation |

| Allegory | The colonel and his household | The poem operates as an allegory of authoritarian regimes, with the colonel embodying institutionalized state violence rather than an individual villain. |

| Allusion | “There were daily papers… On the television was a cop show.” | These references to mass media allude to modern global culture, showing how brutality coexists with everyday normalcy. |

| Anecdote | “WHAT YOU HAVE HEARD is true. I was in his house.” | The poem is structured as a personal anecdote, enhancing its authenticity and testimonial authority. |

| Assonance | “rack of lamb, good wine” | The repetition of vowel sounds creates a smooth, ironic musicality that contrasts sharply with the poem’s violence. |

| Banality of Evil | “We had dinner… good wine” | Ordinary domestic actions illustrate how extreme cruelty becomes normalized under oppressive power structures. |

| Brutal Realism | “He spilled many human ears on the table.” | The direct, unfiltered depiction of violence rejects metaphor and forces the reader to confront atrocity. |

| Colloquialism | “go fuck themselves” | The crude diction reflects the colonel’s contempt for moral and human rights discourse. |

| Contrast (Juxtaposition) | Civilized dinner setting vs. severed ears | The juxtaposition of refinement and horror intensifies the poem’s moral and emotional impact. |

| Documentary Mode | “There is no other way to say this.” | The speaker asserts factual precision, positioning the poem as testimony rather than imaginative abstraction. |

| Dramatic Irony | “Something for your poetry, no?” | The colonel mocks poetry, yet the poem itself becomes an act of resistance and exposure. |

| Imagery | “They were like dried peach halves.” | Vivid visual imagery renders violence concrete and unforgettable. |

| Metonymy | “human ears” | The ears stand in for silenced victims, reduced to body parts by state terror. |

| Moral Shock | The sudden spilling of ears on the table | The abrupt revelation disrupts reader expectations and provokes ethical outrage. |

| Parataxis | Short, sequential sentences throughout | The lack of explanatory transitions mirrors the mechanical, normalized flow of violence. |

| Personification | “Some of the ears… caught this scrap of his voice.” | Human qualities attributed to the ears suggest that testimony persists even after death. |

| Political Satire | “As for the rights of anyone…” | The colonel’s speech satirizes authoritarian dismissal of human rights language. |

| Repetition | “Some of the ears… Some of the ears…” | Repetition reinforces the haunting persistence of listening and witnessing. |

| Shock Value | Display of mutilated ears | Shock is deliberately employed to break reader complacency and moral distance. |

| Symbolism | Ears | The ears symbolize listening, truth, and the suppressed voices of victims. |

| Testimonial Voice | First-person observer narrator | The speaker bears witness, transforming poetry into an ethical and historical record. |

Themes: “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

- State Violence and the Normalization of Atrocity

The Colonel by Carolyn Forché exposes how extreme state violence becomes disturbingly normalized within authoritarian power structures, presenting brutality not as an aberration but as an everyday administrative reality. The poem situates political terror within a domestic setting—coffee trays, family routines, polite conversation—thereby collapsing the boundary between private life and institutional cruelty. This normalization is most powerfully articulated through the colonel’s casual display of severed human ears, which are treated not as evidence of crime but as conversational props. The horror lies not merely in the violence itself but in the perpetrator’s ease, his bureaucratic confidence, and his belief that governance necessitates such acts. Forché thus critiques a system in which violence is routinized, justified through political rhetoric, and absorbed into social custom. The poem forces readers to confront how authoritarian regimes depend not only on coercion but also on the moral desensitization of those who exercise power.

- Silencing, Surveillance, and the Politics of Listening

The Colonel by Carolyn Forché centrally interrogates the politics of listening, using the recurring motif of ears to symbolize surveillance, silenced dissent, and the contested terrain of testimony. The severed ears represent those who once listened, spoke, or resisted, and whose punishment was mutilation—both literal and symbolic. In this context, the act of listening becomes politically dangerous, while enforced silence becomes a tool of governance. The colonel’s obsession with ears reflects a regime that fears what it cannot fully control: memory, communication, and the circulation of truth. Even after being discarded, some ears are described as “pressed to the ground,” suggesting that suppressed voices continue to listen, record, and bear witness beyond death. Through this unsettling image, Forché asserts that authoritarian power can maim bodies but cannot fully extinguish perception or historical memory, thereby reaffirming listening as a form of resistance.

- Poetry as Witness and Ethical Responsibility

The Colonel by Carolyn Forché positions poetry as an ethical act of witnessing rather than aesthetic detachment, explicitly challenging the poet’s role in relation to political violence. The colonel’s taunting remark—“Something for your poetry, no?”—forces a confrontation between art and atrocity, implying that poetry risks complicity if it merely observes without moral engagement. Forché rejects the notion of poetry as ornament or escape, instead advancing a poetics grounded in responsibility, testimony, and historical record. The poem functions as documentary evidence, insisting that language must register suffering truthfully, even at the cost of comfort or beauty. By refusing metaphorical distance at key moments, the poem compels readers to acknowledge their own position as witnesses. In this way, poetry becomes not a refuge from violence but a medium through which violence is exposed, remembered, and ethically confronted.

- Hypocrisy of Power and the Illusion of Civility

The Colonel by Carolyn Forché dismantles the illusion of civility that often masks political repression, revealing how refinement and brutality coexist within structures of power. The colonel’s cultivated environment—fine food, polite conversation, cultured manners—stands in grotesque contrast to the violence he orchestrates, highlighting the hypocrisy at the heart of authoritarian leadership. Governance is discussed as a technical difficulty rather than a moral catastrophe, reducing human suffering to an administrative inconvenience. This façade of order allows atrocity to appear rational, even necessary, while insulating perpetrators from accountability. Forché suggests that such hypocrisy is more dangerous than overt barbarism because it normalizes cruelty under the guise of stability and decorum. By exposing this contradiction, the poem critiques not only tyrants but also global audiences who may be seduced by surface civility and fail to interrogate the violence sustaining it.

Literary Theories and “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

| Literary Theory | Application to “The Colonel” (with Textual References & Symbols) |

| New Historicism | New Historicism reads “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché as a text embedded within the historical realities of Cold War–era Latin American dictatorships, particularly El Salvador. The poem does not fictionalize violence but records it as lived history, blurring the boundary between literature and political document. References such as “There were daily papers… a pistol on the cushion beside him” and “There was some talk then of how difficult it had become to govern” situate the poem within a specific socio-political discourse of authoritarian rule and U.S.-backed regimes. The colonel’s language reflects official state rhetoric that normalizes terror as governance. New Historicism emphasizes that the poem is not merely about power but is itself a cultural artifact shaped by—and responding to—real historical trauma. |

| Marxist Criticism | From a Marxist perspective, “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché exposes how state violence functions as an instrument of class domination and ideological control. The colonel embodies the ruling elite, enjoying material comfort—“rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell”—while enforcing terror on the oppressed masses. The severed ears symbolize the silencing of subaltern voices and the destruction of collective resistance. Governance is framed as a technical challenge rather than a moral issue, reflecting how power justifies exploitation through bureaucratic language. The poem critiques the material inequalities that allow the ruling class to convert human suffering into spectacle, revealing how ideology masks violence in order to preserve political and economic hierarchies. |

| Postcolonial Theory | Postcolonial theory interprets “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché as a critique of neo-imperial power structures and their internal collaborators. The presence of English-language television—“On the television was a cop show. It was in English”—signals cultural imperialism and Western normalization of authoritarian regimes. The colonel’s dismissal of human rights—“tell your people they can go fuck themselves”—directly challenges Western liberal discourse while simultaneously exposing its limited enforcement power. The poem suggests that postcolonial states often replicate colonial violence internally, turning their own citizens into subjects of terror. Forché positions the poet as a transnational witness, implicating global power networks rather than isolating brutality within a single nation. |

| Feminist / Ethical Criticism | Through a feminist and ethical lens, “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché interrogates power, voice, and moral responsibility rather than gender alone. The poet-speaker occupies a vulnerable position, silenced by fear—“My friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing”—highlighting how authoritarian systems suppress testimony. The domestic space, traditionally associated with safety, becomes a site of terror, implicating everyday social structures in violence. Ethical criticism emphasizes the poem’s demand that witnessing entails responsibility; the colonel’s mockery—“Something for your poetry, no?”—forces poetry to confront its moral obligations. The poem insists that ethical engagement, not aesthetic distance, is the writer’s primary duty in the face of atrocity. |

Critical Questions about “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

◆ Question 1: How does the poem transform personal witnessing into political testimony?

“The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché transforms private observation into public testimony by positioning the speaker as a reluctant but ethically compelled witness to state-sponsored violence, thereby collapsing the boundary between personal experience and political responsibility. The poem opens with an assertion of truth—“WHAT YOU HAVE HEARD is true”—which establishes a testimonial framework rather than a lyrical one, and this insistence on factual accuracy continues through the speaker’s restrained, documentary tone. By narrating ordinary domestic details alongside extraordinary cruelty, the speaker refuses sensationalism and instead allows the facts themselves to indict the regime. Moreover, the speaker’s silence—reinforced by the warning “say nothing”—mirrors the enforced muteness of victims, making the act of later narration a form of resistance. Through this strategy, Forché turns poetry into an archival space where suppressed histories are preserved, ensuring that private witnessing becomes a moral and political act addressed to the global reader.

● Question 2: In what ways does the poem critique the relationship between power and language?

“The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché offers a profound critique of how authoritarian power manipulates, empties, and ultimately destroys language, particularly the language of rights and morality. The colonel’s explicit dismissal of human rights—“tell your people they can go fuck themselves”—demonstrates how political authority reduces ethical discourse to obscenity, replacing reasoned governance with brute force. Language in the poem is repeatedly shown to fail: conversation drifts aimlessly, television broadcasts are trivial, and even poetry is mocked as a decorative afterthought to violence. Yet, paradoxically, the poem itself resists this collapse by insisting on precise description, most notably in the line “There is no other way to say this,” which asserts the necessity of naming atrocity accurately. The severed ears, symbols of listening and speech, further reinforce this critique by embodying silenced voices, suggesting that when power annihilates language, poetry must reclaim it as an instrument of truth.

■ Question 3: How does juxtaposition function as a moral strategy in the poem?

“The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché employs stark juxtaposition as a deliberate moral strategy designed to expose the normalization of terror within structures of everyday life. The calm domestic setting—complete with family rituals, fine food, polite conversation, and even a parrot—stands in chilling contrast to the sudden appearance of mutilated human ears, creating a cognitive and ethical dissonance for the reader. This contrast forces an awareness that violence is not an aberration but an integrated feature of authoritarian governance, comfortably coexisting with bourgeois refinement. By refusing transitional commentary, Forché allows the juxtaposition itself to perform the ethical work, compelling readers to confront how easily atrocity is accommodated within systems of privilege and power. The technique dismantles any illusion that brutality occurs only in chaotic or visibly monstrous spaces, revealing instead that the most extreme violence often operates behind polished surfaces, sustained by social rituals that conceal moral collapse.

▲ Question 4: What is the significance of the poem’s final image of the ears “pressed to the ground”?

“The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché concludes with one of the most haunting images in contemporary political poetry, as the ears “pressed to the ground” signify the persistence of listening, memory, and testimony even after extreme dehumanization. This image reverses the colonel’s attempt to render his victims silent, suggesting that truth cannot be fully eradicated by violence. Although the ears are severed from bodies, they retain a symbolic capacity to hear, implying that the oppressed continue to bear witness beyond death and that history itself remains attentive to injustice. The line also implicates the reader, who becomes the one now listening, positioned ethically as a receiver of this testimony. In this way, the poem refuses closure or consolation, ending instead with an enduring demand for attention and accountability, reinforcing Forché’s central claim that poetry must serve as a site of moral listening in the aftermath of political terror.

Literary Works Similar to “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

- “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen: This poem parallels The Colonel by Carolyn Forché in its uncompromising exposure of political violence, rejecting patriotic or official narratives by presenting bodily suffering and death in stark, graphic detail to indict systems of power that normalize human brutality.

- “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London” by Dylan Thomas: Like The Colonel by Carolyn Forché, this poem confronts mass violence through an ethical lens, transforming individual loss into collective testimony while questioning how language and art can respond responsibly to atrocity without aestheticizing suffering.

Representative Quotations of “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

| Quotation | Context & Theoretical Perspective | Explanation |

| ◆ “WHAT YOU HAVE HEARD is true. I was in his house.” | Testimony Theory / Ethics of Witnessing | The opening line establishes the poem as testimonial rather than imaginative, grounding it in factual witnessing and asserting moral responsibility toward historical truth. |

| ● “There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the cushion beside him.” | Banality of Evil / Political Sociology | Ordinary domestic objects coexist with instruments of violence, illustrating how authoritarian terror becomes normalized within everyday life. |

| ■ “Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house…” | Structural Violence / Foucaultian Power | The house itself becomes a weapon, symbolizing how violence is architecturally and systemically embedded in regimes of control. |

| ▲ “We had dinner, rack of lamb, good wine…” | Juxtaposition / Moral Philosophy | The refined meal contrasts sharply with brutality, exposing moral collapse beneath surfaces of civility and privilege. |

| ★ “There is no other way to say this.” | Anti-Aesthetic Realism / Documentary Poetics | This line rejects metaphor and insists on linguistic precision, asserting that atrocity demands direct naming rather than poetic embellishment. |

| ✦ “He spilled many human ears on the table.” | Trauma Theory / Shock Aesthetics | The graphic image confronts the reader with physical evidence of state violence, disrupting emotional distance and passive consumption. |

| ◆ “As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck themselves.” | Human Rights Discourse / Authoritarian Ideology | The colonel’s language reveals the outright rejection of universal rights, reducing ethical principles to objects of mockery. |

| ● “Something for your poetry, no?” | Metapoetry / Power vs. Art | This taunt challenges the legitimacy of poetry, while paradoxically proving its necessity as a mode of resistance and documentation. |

| ■ “Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice.” | Personification / Post-Traumatic Memory | The ears are endowed with agency, suggesting that victims continue to register truth even after death. |

| ▲ “Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.” | Collective Memory / Politics of Listening | The final image implies enduring witness and historical listening, transferring ethical responsibility to the reader and society at large. |

Suggested Readings: “The Colonel” by Carolyn Forché

- Baniewicz, Christine. “A Painful Turning: American Confessional Poets on Human Suffering Abroad.” Ellipsis: A Journal of Art, Ideas, and Literature, vol. 43, 2016, article 5, https://scholarworks.uno.edu/ellipsis/vol43/iss1/5/. Accessed 21 Jan. 2026.

- Blumenfeld, Emily R. “Poetry of Witness, Survivor Silence, and the Healing Use of the Poetic.” Journal of Poetry Therapy, vol. 24, no. 2, 2011, pp. 71–78. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233089773_Poetry_of_witness_survivor_silence_and_the_healing_use_of_the_poetic. Accessed 21 Jan. 2026. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2011.573283.

- Forché, Carolyn. The Country Between Us. Harper & Row, 1981. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Country_Between_Us.html?id=JDPuAAAAMAAJ. Accessed 21 Jan. 2026.

- Forché, Carolyn, and Duncan Wu, editors. Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500–2001. W. W. Norton, 2014. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books/about/Poetry_of_Witness.html?id=0FiNEAAAQBAJ. Accessed 21 Jan. 2026.

- Forché, Carolyn. “The Colonel.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/49862/the-colonel. Accessed 21 Jan. 2026.

- Forché, Carolyn. “The Colonel.” Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, https://poets.org/poem/colonel. Accessed 21 Jan. 2026.