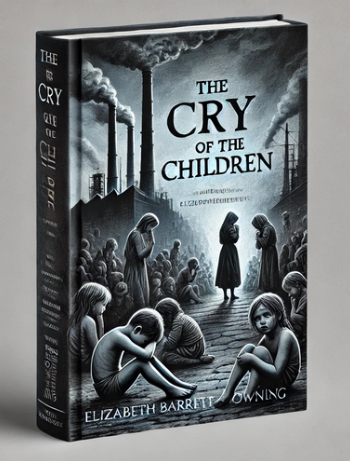

Introduction: “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning first appeared in 1843 as part of a collection published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. The poem is a poignant critique of the exploitation of child labor during the Industrial Revolution in England, highlighting the physical and emotional suffering of children forced to work in harsh conditions. Its vivid imagery and empathetic tone effectively convey the plight of these young workers, resonating with contemporary social reform movements. The poem’s enduring popularity as a textbook example lies in its powerful social commentary, its role in sparking discussions about labor rights, and its embodiment of Victorian-era concerns about morality and justice. It serves as a classic illustration of how literature can act as a catalyst for societal change.

Text: “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Pheu pheu, ti prosderkesthe m ommasin, tekna;”

[[Alas, alas, why do you gaze at me with your eyes, my children.]]—Medea.

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years ?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers, —

And that cannot stop their tears.

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows ;

The young birds are chirping in the nest ;

The young fawns are playing with the shadows ;

The young flowers are blowing toward the west—

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

They are weeping bitterly !

They are weeping in the playtime of the others,

In the country of the free.

Do you question the young children in the sorrow,

Why their tears are falling so ?

The old man may weep for his to-morrow

Which is lost in Long Ago —

The old tree is leafless in the forest —

The old year is ending in the frost —

The old wound, if stricken, is the sorest —

The old hope is hardest to be lost :

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

Do you ask them why they stand

Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers,

In our happy Fatherland ?

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their looks are sad to see,

For the man’s grief abhorrent, draws and presses

Down the cheeks of infancy —

“Your old earth,” they say, “is very dreary;”

“Our young feet,” they say, “are very weak !”

Few paces have we taken, yet are weary—

Our grave-rest is very far to seek !

Ask the old why they weep, and not the children,

For the outside earth is cold —

And we young ones stand without, in our bewildering,

And the graves are for the old !”

“True,” say the children, “it may happen

That we die before our time !

Little Alice died last year her grave is shapen

Like a snowball, in the rime.

We looked into the pit prepared to take her —

Was no room for any work in the close clay :

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her,

Crying, ‘Get up, little Alice ! it is day.’

If you listen by that grave, in sun and shower,

With your ear down, little Alice never cries ;

Could we see her face, be sure we should not know her,

For the smile has time for growing in her eyes ,—

And merry go her moments, lulled and stilled in

The shroud, by the kirk-chime !

It is good when it happens,” say the children,

“That we die before our time !”

Alas, the wretched children ! they are seeking

Death in life, as best to have !

They are binding up their hearts away from breaking,

With a cerement from the grave.

Go out, children, from the mine and from the city —

Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do —

Pluck you handfuls of the meadow-cowslips pretty

Laugh aloud, to feel your fingers let them through !

But they answer, ” Are your cowslips of the meadows

Like our weeds anear the mine ?

Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows,

From your pleasures fair and fine!

“For oh,” say the children, “we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap —

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

Our knees tremble sorely in the stooping —

We fall upon our faces, trying to go ;

And, underneath our heavy eyelids drooping,

The reddest flower would look as pale as snow.

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring,

Through the coal-dark, underground —

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.

“For all day, the wheels are droning, turning, —

Their wind comes in our faces, —

Till our hearts turn, — our heads, with pulses burning,

And the walls turn in their places

Turns the sky in the high window blank and reeling —

Turns the long light that droppeth down the wall, —

Turn the black flies that crawl along the ceiling —

All are turning, all the day, and we with all ! —

And all day, the iron wheels are droning ;

And sometimes we could pray,

‘O ye wheels,’ (breaking out in a mad moaning)

‘Stop ! be silent for to-day ! ‘ “

Ay ! be silent ! Let them hear each other breathing

For a moment, mouth to mouth —

Let them touch each other’s hands, in a fresh wreathing

Of their tender human youth !

Let them feel that this cold metallic motion

Is not all the life God fashions or reveals —

Let them prove their inward souls against the notion

That they live in you, or under you, O wheels ! —

Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward,

As if Fate in each were stark ;

And the children’s souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark.

Now tell the poor young children, O my brothers,

To look up to Him and pray —

So the blessed One, who blesseth all the others,

Will bless them another day.

They answer, ” Who is God that He should hear us,

While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred ?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us

Pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word !

And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)

Strangers speaking at the door :

Is it likely God, with angels singing round Him,

Hears our weeping any more ?

” Two words, indeed, of praying we remember ;

And at midnight’s hour of harm, —

‘Our Father,’ looking upward in the chamber,

We say softly for a charm.

We know no other words, except ‘Our Father,’

And we think that, in some pause of angels’ song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong.

‘Our Father !’ If He heard us, He would surely

(For they call Him good and mild)

Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely,

‘Come and rest with me, my child.’

“But, no !” say the children, weeping faster,

” He is speechless as a stone ;

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on.

Go to ! ” say the children,—”up in Heaven,

Dark, wheel-like, turning clouds are all we find !

Do not mock us ; grief has made us unbelieving —

We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.”

Do ye hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye preach ?

For God’s possible is taught by His world’s loving —

And the children doubt of each.

And well may the children weep before you ;

They are weary ere they run ;

They have never seen the sunshine, nor the glory

Which is brighter than the sun :

They know the grief of man, without its wisdom ;

They sink in the despair, without its calm —

Are slaves, without the liberty in Christdom, —

Are martyrs, by the pang without the palm, —

Are worn, as if with age, yet unretrievingly

No dear remembrance keep,—

Are orphans of the earthly love and heavenly :

Let them weep ! let them weep !

They look up, with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they think you see their angels in their places,

With eyes meant for Deity ;—

“How long,” they say, “how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart, —

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart ?

Our blood splashes upward, O our tyrants,

And your purple shews your path ;

But the child’s sob curseth deeper in the silence

Than the strong man in his wrath !”

Annotations: “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

| Stanza | Annotation |

| Epigraph | The opening quote from Medea reflects the grief and despair of children, a theme central to the poem. Medea’s cry of anguish parallels the lament of the exploited children in the Industrial Revolution. |

| 1st Stanza | The children’s weeping contrasts with the joy of nature (lambs, birds, fawns). This juxtaposition highlights the unnatural suffering of children in a supposedly free and prosperous country. The rhetorical question “Do ye hear?” engages the audience and underscores their ignorance or apathy. |

| 2nd Stanza | This stanza contrasts the sorrow of children with that of the elderly. While old age brings natural grief, the suffering of children is unnatural and premature, challenging the ideal of a “happy Fatherland.” The image of children weeping before their mothers emphasizes their vulnerability. |

| 3rd Stanza | The children describe their world as “dreary,” emphasizing their physical weakness and emotional despair. Their exhaustion reflects the relentless labor they endure. The concept of graves as a “rest” exposes the horrifying reality that death is preferable to their current existence. |

| 4th Stanza | Using the example of “little Alice,” the stanza illustrates how death brings release from suffering. The grave becomes a sanctuary, contrasting with the oppressive lives of the children. The imagery of the smiling, peaceful dead contrasts with the weary living, intensifying the tragedy. |

| 5th Stanza | The children lament that life has become a form of living death, binding their hearts in grave-like silence. Calls to enjoy nature fall on deaf ears, as the children, burdened by labor, see no beauty in the world. The “weeds anear the mine” symbolize their bleak reality. |

| 6th Stanza | The children express their inability to partake in joy or physical play due to exhaustion from labor. Their description of trembling knees and drooping eyelids highlights their physical deterioration. Nature’s vibrancy pales against the monotony of their toil underground or in factories. |

| 7th Stanza | The relentless turning of factory wheels symbolizes the mechanical, dehumanizing labor the children endure. The “turning” imagery extends to their environment (walls, sky, ceiling), showing how every aspect of their lives revolves around oppressive labor. The children’s cry for the wheels to stop conveys their desperation. |

| 8th Stanza | The plea for silence underscores the children’s yearning for human connection and relief. The “cold metallic motion” contrasts with the warmth of human interaction. The stanza critiques how industrialization reduces human souls to mere cogs in a machine. |

| 9th Stanza | The children question the effectiveness of prayer, as the noise of the machines drowns their cries. This highlights their spiritual alienation and growing disbelief in divine intervention. The industrial world has eroded their faith in God and humanity alike. |

| 10th Stanza | The children’s fragmented prayers (“Our Father”) symbolize their limited access to spiritual solace. Their perception of God as distant reflects the failure of religious institutions to alleviate their suffering. This stanza critiques society’s hypocrisy in preaching faith while ignoring the children’s plight. |

| 11th Stanza | The children’s disbelief grows as they view God as silent and powerless. The metaphor of “wheel-like, turning clouds” in heaven parallels the relentless wheels of industry, suggesting that even divine realms are mechanical and indifferent. Their loss of faith reflects their despair. |

| 12th Stanza | This stanza contrasts the children’s premature grief with the wisdom that comes with age. Their suffering is unnatural and devoid of consolation. The comparison to martyrs without recognition intensifies the sense of injustice and neglect. |

| 13th Stanza | The children’s “pale and sunken faces” evoke pity and horror. They accuse society of exploiting their innocence for economic gain, with the “mailed heel” imagery symbolizing oppression. The final lines warn that the silent curse of children is more damning than any overt rebellion. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

| Literary Device | Example | Explanation |

| Alliteration | “Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers” | The repetition of the “b” sound emphasizes the sorrow and vulnerability of the children. |

| Allusion | “Pheu pheu, ti prosderkesthe m ommasin, tekna;” (Epigraph from Medea) | The reference to Medea aligns the suffering of the children with Greek tragedy, emphasizing their plight. |

| Anaphora | “The young… The young… The young…” | The repetition of “The young” highlights the contrast between the vibrancy of youth in nature and the suffering of the children. |

| Apostrophe | “O my brothers” | The speaker directly addresses the audience to appeal to their compassion and evoke responsibility. |

| Assonance | “Are worn, as if with age, yet unretrievingly” | The repetition of vowel sounds (“o,” “a,” and “e”) creates a mournful tone. |

| Caesura | “And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)” | The pause within the line reflects the interruption caused by the relentless noise of the machines. |

| Contrast | “The young lambs are bleating in the meadows; But the young, young children… are weeping bitterly” | Contrasts the innocence and joy of nature with the sorrow of the children, emphasizing the unnatural suffering they endure. |

| Enjambment | “For all day, the wheels are droning, turning, — / Their wind comes in our faces,” | The continuation of the sentence across lines mirrors the relentless motion of the factory wheels. |

| Epistrophe | “Turns the sky… Turns the long light… Turn the black flies…” | Repetition of “turns” at the beginning of successive clauses emphasizes the monotonous, mechanical motion surrounding the children. |

| Hyperbole | “Our blood splashes upward” | Exaggerates the children’s suffering to emphasize its severity and societal impact. |

| Imagery | “Pale and sunken faces” | Creates a vivid picture of the children’s physical suffering and despair. |

| Irony | “In the country of the free” | The phrase is ironic as it contrasts the suffering of children with the supposed freedom and prosperity of the nation. |

| Juxtaposition | “Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do” vs. “Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows” | Juxtaposes the joy of nature with the despair of the children’s reality, heightening the tragic tone. |

| Metaphor | “Cold metallic motion” | Compares industrial machinery to something lifeless and unfeeling, symbolizing the dehumanization caused by industrialization. |

| Onomatopoeia | “The wheels are droning, turning” | The word “droning” imitates the sound of the machines, making the reader feel the oppressive industrial noise. |

| Personification | “The old hope is hardest to be lost” | Personifies hope as something that can be “lost,” emphasizing the emotional impact of despair. |

| Rhetorical Question | “Do you hear the children weeping, O my brothers?” | Invites the reader to reflect on their own indifference to the children’s suffering. |

| Repetition | “Young, young children” | The repetition of “young” intensifies the focus on the innocence and vulnerability of the children. |

| Simile | “Her grave is shapen / Like a snowball, in the rime” | Compares Alice’s grave to a snowball, highlighting the coldness and stillness of death. |

| Symbolism | “The wheels” | Symbolize the relentless, dehumanizing force of industrial labor, consuming the children’s lives. |

Themes: “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

1. Exploitation of Children

One of the central themes of The Cry of the Children is the exploitation of children during the Industrial Revolution. Elizabeth Barrett Browning vividly portrays the suffering of young laborers in mines and factories, highlighting their physical and emotional exhaustion. Lines such as “For all day, we drag our burden tiring, / Through the coal-dark, underground” reveal the grueling conditions the children endure. Their labor is likened to a form of living death, as they lament, “We are weary, / And we cannot run or leap.” Browning’s use of vivid imagery and repetitive descriptions of their weariness underscores the unnatural and inhumane demands placed on children, drawing attention to the moral failure of a society that sacrifices its most vulnerable for economic gain.

2. Loss of Innocence

The poem emphasizes the premature loss of innocence among the children, who experience profound sorrow instead of the joy and freedom typical of youth. Browning contrasts the natural world’s vitality—”The young lambs are bleating in the meadows; / The young birds are chirping in the nest”—with the bitter tears of the children: “But the young, young children… are weeping bitterly.” This juxtaposition highlights how industrialization strips children of their childhood, replacing innocence with despair. Furthermore, their exposure to death at a young age, as seen in the line, “Little Alice died last year her grave is shapen,” intensifies the tragic loss of innocence. The poem reveals the devastating emotional toll of industrial labor, which denies children the carefree experiences of youth.

3. Spiritual Alienation

Another significant theme is the spiritual alienation caused by relentless suffering. The children express doubt in divine justice, questioning, “Who is God that He should hear us, / While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred?” The industrial environment, symbolized by the incessant turning of wheels, drowns out both their prayers and any sense of divine presence. Browning portrays how the children’s faith is eroded by their experiences, as they state, “We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.” This spiritual alienation not only reflects their personal despair but also critiques a society that values economic progress over moral responsibility, leaving the children abandoned by both man and God.

4. Social Injustice

Browning critiques the social injustice inherent in a system that prioritizes industrial and economic growth over human well-being. The poem’s repeated address to “O my brothers” serves as a direct appeal to the readers, urging them to acknowledge their complicity in perpetuating the children’s suffering. The line, “How long, O cruel nation, / Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart,” accuses society of building its prosperity on the physical and emotional exploitation of children. The vivid image of “blood splashes upward” symbolizes the cost of industrial progress, while the “child’s sob curseth deeper in the silence” serves as a haunting reminder of the moral consequences of ignoring their plight. Through these indictments, Browning calls for social reform and moral accountability.

Literary Theories and “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

| Literary Theory | Application to the Poem | References from the Poem |

| Marxist Criticism | The poem critiques the capitalist exploitation of child labor during the Industrial Revolution. It highlights class oppression and economic inequality. | The line, “How long, O cruel nation, / Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart,” condemns the industrial system that profits from children’s suffering. |

| Feminist Criticism | Browning, as a woman poet, gives voice to the powerless children, often aligning their plight with societal neglect of vulnerable groups. | The repeated address to “O my brothers” implies a patriarchal audience, critiquing their indifference to the suffering of children, particularly those reliant on maternal care. |

| Ecocriticism | The poem contrasts the vibrant, natural world with the bleak, industrialized settings where children suffer, highlighting the destructive effects of industrialization. | The juxtaposition of “The young lambs are bleating in the meadows” with “Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows” illustrates the loss of harmony with nature. |

Critical Questions about “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

1. How does Elizabeth Barrett Browning critique the industrialization of Victorian society through the poem?

Browning’s poem serves as a powerful critique of the Industrial Revolution, emphasizing the human cost of industrial progress. She highlights how the mechanization of labor dehumanizes workers, particularly children, who are reduced to cogs in the industrial machine. The relentless motion of the “iron wheels” symbolizes the inescapable and oppressive force of industrialization: “For all day, the wheels are droning, turning.” Browning juxtaposes the natural world’s freedom and vibrancy—”The young lambs are bleating in the meadows”—with the children’s sorrowful reality in the “dark of the coal-shadows.” This stark contrast underscores how industrialization not only exploits human life but also disconnects society from the natural world, transforming it into a bleak and oppressive environment. The poem critiques the moral bankruptcy of a society that prioritizes economic growth over the well-being of its people, especially its youngest and most vulnerable members.

2. How does the poem explore the theme of spiritual alienation among the children?

Browning portrays spiritual alienation as a direct result of the children’s relentless suffering, suggesting that their faith has been eroded by the harsh realities of their lives. The poem asks, “Who is God that He should hear us, / While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred?” Here, the noise of industrial machines drowns out both the children’s prayers and any sense of divine presence. The children’s fragmented prayer, reduced to the simple phrase “Our Father,” highlights their limited spiritual connection, further underscored by their belief that God is unresponsive: “He is speechless as a stone.” This alienation extends beyond religion to a broader critique of Victorian society, which has abandoned its moral and spiritual responsibility to protect its most vulnerable members. Browning uses this theme to underline the devastating psychological impact of labor exploitation, which strips children not only of their physical well-being but also their hope and faith.

3. What role does nature play in the poem, and how does it contrast with the children’s reality?

Nature in The Cry of the Children is presented as a symbol of innocence, freedom, and vitality, in stark contrast to the oppressive and unnatural conditions of the children’s lives. Browning uses imagery of vibrant natural life—”The young lambs are bleating in the meadows; / The young birds are chirping in the nest”—to underscore what the children are denied. The contrast becomes even starker when the children respond with, “Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows.” This response reflects their alienation from the natural world, which has become irrelevant in their world of relentless labor and despair. Nature also serves as a moral backdrop, emphasizing the unnaturalness of the children’s suffering and the moral failing of a society that allows it. Browning’s use of nature as a foil to industrialization critiques the broader societal disconnect from humanity and the environment.

4. How does Browning evoke empathy and call for social reform in the poem?

Browning employs rhetorical devices, vivid imagery, and direct appeals to evoke empathy for the children and call for social reform. The repeated address to “O my brothers” personalizes the issue, urging readers to acknowledge their complicity in perpetuating the children’s suffering. Browning uses haunting imagery, such as “pale and sunken faces” and “our grave-rest is very far to seek,” to make the children’s plight visceral and immediate. The line, “How long, O cruel nation, / Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart,” directly challenges societal priorities, calling for a moral reckoning. By juxtaposing the children’s suffering with the indifference of their “happy Fatherland,” Browning critiques the hypocrisy of a nation that prides itself on freedom while exploiting its own people. The poem’s emotional appeal and moral urgency serve as a call to action, urging readers to advocate for social and labor reform.

Literary Works Similar to “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- “The Chimney Sweeper” by William Blake

Similarity: This poem, like The Cry of the Children, critiques child labor and exploitation during the Industrial Revolution, focusing on the innocence lost and the suffering endured by young workers. - “London” by William Blake

Similarity: Both poems expose the harsh realities of industrialized society, with a focus on the moral and social decay caused by economic greed and systemic oppression. - “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

Similarity: This poem parallels Browning’s themes by portraying the relentless labor and suffering of the working poor, particularly women, highlighting societal neglect and injustice. - “A Voice from the Factories” by Caroline Norton

Similarity: Norton’s poem specifically focuses on child labor in coal mines, mirroring Browning’s emotional appeal and vivid imagery to elicit empathy and call for reform.

Representative Quotations of “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers?” | The opening line addresses the audience directly, highlighting the children’s suffering and society’s apathy. | Marxist Criticism: Critiques the class inequality that forces children into labor for economic profit. |

| “They are weeping in the playtime of the others, / In the country of the free.” | Contrasts the children’s suffering with the supposed freedom and prosperity of their nation. | Postcolonial Criticism: Challenges the national myth of freedom by exposing internal exploitation. |

| “The young birds are chirping in the nest; / But the young, young children… are weeping bitterly.” | Juxtaposes the innocence of nature with the misery of the children. | Ecocriticism: Highlights the disconnection between human life and the natural world. |

| “For all day, we drag our burden tiring, / Through the coal-dark, underground.” | Describes the harsh physical labor and exhaustion faced by the children. | Marxist Criticism: Illustrates the exploitation of children as a result of industrial capitalism. |

| “How long, O cruel nation, / Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart?” | Critiques societal indifference to the suffering of children in pursuit of progress. | Moral Philosophy: Questions the ethical compromises made for economic growth. |

| “Our grave-rest is very far to seek!” | The children express that even the relief of death feels unattainable amidst their suffering. | Existentialism: Reflects the despair and lack of agency in the children’s lives. |

| “We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.” | Highlights the spiritual alienation and loss of faith among the suffering children. | Theology and Religious Criticism: Critiques the failure of religious institutions to address social issues. |

| “Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward, / As if Fate in each were stark.” | The relentless wheels symbolize the inescapable oppression of industrial labor. | Symbolism: Represents the dehumanizing force of industrialization and its impact on human lives. |

| “Little Alice died last year her grave is shapen / Like a snowball, in the rime.” | Uses the death of a child as an example of the toll labor takes on young lives. | Feminist Criticism: Highlights the societal neglect of vulnerable groups, particularly women and children. |

| “The child’s sob curseth deeper in the silence / Than the strong man in his wrath.” | Suggests the silent suffering of children carries a more profound moral indictment than overt rebellion. | Moral Philosophy: Argues that passive suffering is a powerful critique of systemic injustice. |

Suggested Readings: “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- HENRY, PEACHES. “The Sentimental Artistry of Barrett Browning’s ‘The Cry of the Children.'” Victorian Poetry, vol. 49, no. 4, 2011, pp. 535–56. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23079671. Accessed 19 Dec. 2024.

- Arinshtein, Leonid M. “‘A Curse for a Nation’: A Controversial Episode in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Political Poetry.” The Review of English Studies, vol. 20, no. 77, 1969, pp. 33–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/512974. Accessed 19 Dec. 2024.

- Donaldson, Sandra. “‘Motherhood’s Advent in Power’: Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Poems About Motherhood.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 18, no. 1, 1980, pp. 51–60. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40002713. Accessed 19 Dec. 2024.