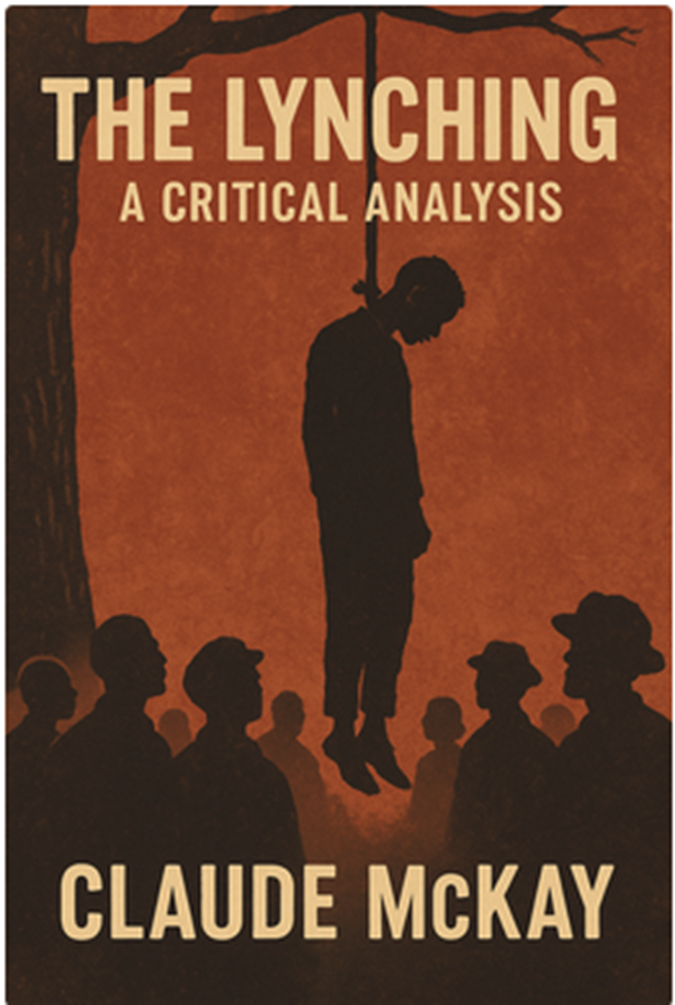

Introduction: “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

“The Lynching” by Claude McKay first appeared in his 1922 collection Harlem Shadows (Harcourt Brace and Company), one of the earliest works to bring the brutal realities of American racial violence into the Harlem Renaissance literary canon. The poem confronts the horror of lynching by combining biblical allusions with stark imagery of a murdered Black man whose “spirit in smoke ascended to high heaven” and whose body “sway[ed] in the sun” for public spectacle. McKay’s use of the Shakespearean sonnet form intensifies the tension between beauty of form and atrocity of subject, making the poem unforgettable. Its popularity stems from its fearless depiction of both the inhumanity of white spectators—“the women thronged to look, but never a one / Showed sorrow in her eyes of steely blue”—and the inherited cycle of racial hatred symbolized by the boys who “danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee.” By blending religious imagery, irony, and protest, McKay transformed the poem into both a work of mourning and a searing indictment of racial injustice, which secured its place as a landmark text of African American protest literature.

Text: “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

His spirit in smoke ascended to high heaven.

His father, by the cruelest way of pain,

Had bidden him to his bosom once again;

The awful sin remained still unforgiven.

All night a bright and solitary star

(Perchance the one that ever guided him,

Yet gave him up at last to Fate’s wild whim)

Hung pitifully o’er the swinging char.

Day dawned, and soon the mixed crowds came to view

The ghastly body swaying in the sun:

The women thronged to look, but never a one

Showed sorrow in her eyes of steely blue;

And little lads, lynchers that were to be,

Danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee.

Source: Harlem Shadows (Harcourt Brace and Company, 1922)

Annotations: “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

| Line | Annotation (Meaning & Analysis) | Literary Devices |

| His spirit in smoke ascended to high heaven. | The victim’s soul rises upward after death, suggesting martyrdom or transcendence despite the brutal murder. | 🌟 Imagery (smoke, heaven); ✝️ Religious allusion (soul rising); 🎭 Irony (a violent death framed as ascension). |

| His father, by the cruelest way of pain, | “His father” alludes to God, who allowed this suffering, suggesting divine silence or inscrutability. | ⛪ Biblical allusion (God as father); ⚔️ Paradox (cruelest way by divine will). |

| Had bidden him to his bosom once again; | The victim is called back into God’s embrace, but through violence, not peace. | 🤲 Metaphor (bosom = heaven’s embrace); 🕊️ Euphemism for death. |

| The awful sin remained still unforgiven. | Society and God both deny forgiveness—lynching becomes collective condemnation, symbolizing racial injustice. | ⚖️ Moral irony (sin vs. innocence); ⛓️ Theme of injustice. |

| All night a bright and solitary star | The star symbolizes hope, guidance, or fate watching the victim’s ordeal. | 🌟 Symbolism (star = destiny, divine eye); 🌌 Imagery (cosmic loneliness). |

| (Perchance the one that ever guided him, | The star may have been his lifelong guide, now powerless to save him. | 🔮 Personification (star guiding); ❓ Ambiguity (perhaps). |

| Yet gave him up at last to Fate’s wild whim) | Fate is portrayed as cruel, indifferent, abandoning him to lynching. | 🎭 Irony; 🎲 Personification (Fate’s whim). |

| Hung pitifully o’er the swinging char. | The star shines pitifully over the charred body, evoking horror and pity. | 🔥 Imagery (swinging charred body); 😢 Pathos. |

| Day dawned, and soon the mixed crowds came to view | Morning reveals the crime; the community gathers, turning death into spectacle. | 🌅 Imagery (day dawned); 🧑🤝🧑 Social critique. |

| The ghastly body swaying in the sun: | Graphic description of the corpse emphasizes dehumanization. | 🩸 Grotesque imagery; ⚰️ Symbolism (swaying = fragility of life). |

| The women thronged to look, but never a one | Women, expected to show compassion, appear cold and complicit. | 👁️ Irony (no sorrow in women); 🎭 Gender commentary. |

| Showed sorrow in her eyes of steely blue; | Their eyes are described as cold, metallic—symbols of racial indifference. | 🧊 Metaphor (steely blue eyes = inhumanity); 🎨 Color imagery. |

| And little lads, lynchers that were to be, | The next generation is indoctrinated, normalizing racial violence. | 👶 Foreshadowing; 🧑🎓 Social commentary (cycle of hatred). |

| Danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee. | Children dance joyfully around the corpse, symbolizing the perversion of innocence and communal cruelty. | 💃 Grotesque irony; 😈 Oxymoron (fiendish glee); 🎭 Symbolism (joy in horror). |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

| Device | Example from the Poem | Explanation |

| Alliteration 🔠 | “spirit in smoke” | The repetition of the /s/ sound creates a soft, whispering tone, evoking the rise of the soul like smoke. |

| Allusion (Biblical) ⛪ | “His father, by the cruelest way of pain” | Refers to God as the “father,” alluding to Christian imagery of divine will, but here framed in cruelty, creating moral irony. |

| Ambiguity ❓ | “Perchance the one that ever guided him” | The uncertainty of “perchance” shows doubt about divine guidance, suggesting fate or abandonment. |

| Anaphora 🔁 | “His… His…” (lines 1–2) | Repetition at the start of lines emphasizes the victim’s relationship with God and highlights suffering. |

| Antithesis ⚖️ | “Showed sorrow in her eyes of steely blue” | Contrasts expected compassion with cold indifference, heightening the horror of communal detachment. |

| Color Imagery 🎨 | “eyes of steely blue” | Blue eyes symbolize coldness, racial identity, and lack of empathy, creating chilling visual effect. |

| Euphemism 🕊️ | “Had bidden him to his bosom once again” | A gentle phrase for death, masking the brutal violence of lynching under the language of divine embrace. |

| Foreshadowing 👶 | “little lads, lynchers that were to be” | Suggests the continuation of racial violence, showing how children will grow into future perpetrators. |

| Grotesque Imagery 🩸 | “The ghastly body swaying in the sun” | Creates a horrifying visual, emphasizing the brutality and dehumanization of the victim. |

| Imagery (Cosmic) 🌌 | “All night a bright and solitary star” | Evokes loneliness and fate, with the star symbolizing divine witness or destiny’s indifference. |

| Irony 🎭 | “Danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee” | The joy of children at a lynching is grotesquely ironic, showing perversion of innocence. |

| Metaphor 🤲 | “to his bosom once again” | God’s bosom is a metaphor for heaven or afterlife, blending comfort with violence. |

| Moral Irony ⛓️ | “The awful sin remained still unforgiven” | The victim is condemned while real sinners (the lynchers) go unpunished—highlighting racial injustice. |

| Oxymoron 😈 | “fiendish glee” | Combines evil (fiendish) with joy (glee), showing the perverse delight of the crowd. |

| Paradox ⚔️ | “His father… by the cruelest way of pain” | God’s love is shown through cruelty, creating a theological contradiction. |

| Pathos 😢 | “Hung pitifully o’er the swinging char” | Evokes pity and sorrow, forcing the reader to emotionally confront the horror. |

| Personification (Fate) 🎲 | “Fate’s wild whim” | Fate is given human qualities, depicted as capricious and cruel. |

| Religious Symbolism ✝️ | “His spirit in smoke ascended to high heaven” | Uses Christian imagery of the soul ascending, but tied to racial violence, complicating the sacred. |

| Symbolism (Cycle of Violence) 🔄 | “little lads… lynchers that were to be” | Children symbolize the cycle of generational hatred and institutional racism. |

| Visual Contrast 👁️ | “women thronged to look… eyes of steely blue” | Contrasts physical beauty (blue eyes) with moral emptiness, reinforcing the theme of racial coldness. |

Themes: “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

Spiritual Redemption and Unforgiven Sin in “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, the opening lines elevate the tragedy of racial violence into a spiritual dimension. The lynched man’s “spirit in smoke ascended to high heaven,” suggesting martyrdom and transcendence beyond earthly brutality. Yet the poem asserts that “the awful sin remained still unforgiven,” highlighting the unresolved moral stain of lynching (lines 1–4). By framing the victim’s return to “his father, by the cruelest way of pain,” McKay links the event to Christ’s crucifixion, drawing a parallel between racial violence and religious sacrifice. This theme underscores the paradox of a supposed Christian society perpetuating atrocities that defy the very doctrine of redemption it claims to uphold.

Cosmic Witness and Indifference in “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, the act of lynching is situated under the silent gaze of the heavens, represented by “a bright and solitary star” that “hung pitifully o’er the swinging char” (lines 5–8). The star becomes a cosmic witness, evoking pity yet offering no intervention. This celestial imagery contrasts with the brutality of human action, suggesting that while the universe bears witness to injustice, it remains indifferent to human suffering. The star’s inability to alter “Fate’s wild whim” amplifies the theme of abandonment, portraying a world where divine or natural forces observe but do not intervene to stop racial violence.

Public Spectacle and Dehumanization in “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, daylight transforms the atrocity into a macabre spectacle, as “the mixed crowds came to view / The ghastly body swaying in the sun” (lines 9–10). The poem emphasizes the communal participation in this violence, where the lynched man’s body becomes a public display stripped of dignity. The women “showed sorrow in her eyes of steely blue,” embodying cold detachment in the face of atrocity (line 12). By highlighting the lack of compassion, McKay critiques the normalization of violence against Black bodies within society, where racial terror becomes not only tolerated but ritualized as entertainment.

Generational Perpetuation of Violence in “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, perhaps the most chilling image is the presence of children: “little lads, lynchers that were to be, / Danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee” (lines 13–14). This theme illustrates how racial hatred is transmitted across generations, ensuring the continuity of violence. The children’s joyful mimicry of brutality reveals the systemic nature of racism, bred into society from a young age. McKay suggests that lynching is not merely an isolated act of violence but a cultural ritual that indoctrinates future perpetrators, embedding racial terror into the social fabric.

Literary Theories and “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

| Literary Theory | Explanation with References from the Poem |

| 1. New Historicism 📜 | This theory situates the poem in the historical context of early 20th-century America, when lynching of African Americans was widespread. McKay, a Harlem Renaissance poet, highlights how racial violence was normalized as community spectacle. For example, the line “Day dawned, and soon the mixed crowds came to view / The ghastly body swaying in the sun” shows lynching as a public event, reflecting the systemic racism of the Jim Crow era. New Historicism reveals how the poem mirrors and critiques the social, cultural, and political realities of its time. |

| 2. Marxist Criticism ⚒️ | From a Marxist lens, the poem exposes the power structures and class dynamics underpinning racial oppression. The “mixed crowds” who participate in or passively watch the lynching represent the ideological control of the dominant class, where racial hatred serves to maintain hierarchy. The “little lads, lynchers that were to be” symbolize how ideology is reproduced across generations, ensuring continued exploitation and violence against marginalized groups. Marxist reading emphasizes the structural role of race and class in sustaining injustice. |

| 3. Psychoanalytic Criticism 🧠 | Psychoanalytic theory examines the psychological impulses and collective unconscious behind the lynching. The grotesque joy in “Danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee” suggests a perverse sublimation of repressed desires and aggression, projected onto the victim. The women’s “eyes of steely blue” reflect emotional detachment and repression of compassion, revealing a communal pathology. This theory shows the poem as an exploration of the dark, unconscious drives that fuel mob violence and normalize cruelty. |

| 4. Postcolonial Theory 🌍 | Through a postcolonial lens, the poem critiques racial subjugation and dehumanization rooted in colonial ideologies. The victim is reduced to a “swinging char,” symbolizing how black bodies were commodified, objectified, and stripped of humanity. The “awful sin remained still unforgiven” highlights how Western Christian morality was weaponized against black lives, denying forgiveness while justifying violence. The presence of “little lads” shows how colonial legacies reproduce systemic racism. This theory underscores the poem as a resistance text within the Harlem Renaissance’s struggle for identity and liberation. |

Critical Questions about “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

🎭 Question 1: How does McKay use irony to critique society in the poem?

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, irony functions as a sharp critique of communal morality. The grotesque scene where “little lads, lynchers that were to be, / Danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee” inverts the innocence of children into symbols of inherited cruelty. Instead of horror, there is entertainment; instead of sorrow, there is cold fascination. Likewise, the women’s “eyes of steely blue” reflect detachment rather than compassion, undermining expectations of female nurturing. This irony demonstrates McKay’s indictment of a society where violence is normalized, and even the supposed symbols of innocence or moral care are complicit in brutality.

🔥 Question 2: In what ways does McKay use religious imagery to highlight injustice?

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, religious imagery underscores the tension between spiritual ideals and racial reality. The victim’s soul “ascended to high heaven” invokes Christian notions of salvation, yet the following line—“The awful sin remained still unforgiven”—contradicts the promise of redemption, suggesting that even divine justice fails. God as “His father” appears to embrace the victim only “by the cruelest way of pain,” exposing the cruel paradox of suffering tied to spiritual reward. By intertwining religious language with violence, McKay highlights the hypocrisy of a society that used Christianity to justify racial oppression while denying forgiveness and dignity to its victims.

🌌 Question 3: How does the poem reflect generational cycles of racial violence?

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, the presence of children symbolizes the continuity of racial hatred across generations. The line “little lads, lynchers that were to be” suggests how children inherit not only their parents’ cultural values but also their prejudices and capacity for cruelty. Witnessing and celebrating such brutality ensures that violence becomes embedded in the social fabric. The communal glee transforms lynching into both spectacle and education, teaching the young that racial violence is naturalized and even celebrated. McKay thus warns that unless this cycle is broken, the future is destined to replicate the horrors of the past.

⚖️ Question 4: How does McKay challenge the notion of justice in the poem?

In “The Lynching” by Claude McKay, the notion of justice is revealed as distorted and racially unjust. The victim, whose “awful sin remained still unforgiven,” is condemned while the true sinners—the mob—revel freely in their crime. Justice here is not moral or equitable but instead a perverted act of vengeance disguised as righteousness. The image of the “ghastly body swaying in the sun” witnessed by an indifferent crowd further illustrates how justice is replaced with spectacle. By contrasting divine silence, social complicity, and mob cruelty, McKay exposes lynching not as justice but as the collapse of all ethical and spiritual order.

Literary Works Similar to “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

- 🔴 “Strange Fruit” by Abel Meeropol (1937, popularized by Billie Holiday)

Like McKay’s sonnet, this poem uses haunting imagery of a lynched body—“Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze”—to condemn racial violence and its normalization as spectacle. - 🟡 “If We Must Die” by Claude McKay (1919)

Written in response to racial violence during the Red Summer, this poem, like “The Lynching,” uses the sonnet form to protest brutality, but emphasizes collective resistance rather than victimization. - 🔵 “Incident” by Countee Cullen (1925)

This poem parallels “The Lynching” in exposing how racism scars Black identity, with its powerful focus on childhood experience, much like the “little lads” inheriting hatred in McKay’s sonnet. - 🟢 “Bury Me in a Free Land” by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1858)

Harper’s plea to be laid to rest where no enslaved person suffers resonates with McKay’s vision of spiritual suffering and injustice transcending earthly life. - 🟣 “Theme for English B” by Langston Hughes (1951)

While less graphic than “The Lynching,” Hughes’s poem similarly unmasks racial realities in America, blending personal reflection with a critique of systemic injustice that parallels McKay’s social protest.

Representative Quotations of “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| 🔴 “His spirit in smoke ascended to high heaven.” | The victim’s soul is imagined as rising in smoke after death, fusing transcendence with violent destruction. | Religious Criticism & Martyrdom Studies – Suggests a Christ-like sacrifice but highlights irony: salvation comes only through terror, exposing the gap between faith and racial injustice. |

| 🟡 “His father, by the cruelest way of pain, / Had bidden him to his bosom once again.” | Divine imagery presents God as reclaiming the victim, though only via torture. | Theology & Irony – Frames lynching as grotesque parody of Christian redemption, critiquing the church’s complicity in racial violence while exploiting biblical imagery. |

| 🔵 “The awful sin remained still unforgiven.” | America’s collective racial guilt is unatoned for, with lynching presented as national sin. | Critical Race Theory & Moral Philosophy – Exposes racism as a systemic crime embedded in cultural and legal structures, with “sin” symbolizing enduring moral corruption. |

| 🟢 “All night a bright and solitary star / Hung pitifully o’er the swinging char.” | The star, a symbol of divine witness, shines helplessly over atrocity. | Symbolism & Religious Criticism – Cosmic pity contrasts with human cruelty, suggesting the silence of God and the futility of divine signs against systemic violence. |

| 🟣 “Day dawned, and soon the mixed crowds came to view.” | Lynching becomes a ritual of public spectacle attended by people across society. | New Historicism & Cultural Studies – Reads lynching as social theater, part of a broader cultural system that normalized violence through communal participation. |

| 🟠 “The ghastly body swaying in the sun.” | The corpse becomes both symbol and spectacle of racial terror. | Postcolonial Theory & Body Politics – Highlights how Black bodies were objectified, displayed, and disciplined, much like colonial practices of domination and dehumanization. |

| 🔶 “The women thronged to look, but never a one / Showed sorrow in her eyes of steely blue.” | White women’s cold detachment is foregrounded as chilling complicity. | Feminist & Critical Whiteness Studies – Challenges the stereotype of white women as passive, showing their active role in perpetuati |

Suggested Readings: “The Lynching” by Claude McKay

Books

- Cooper, Wayne F. Claude McKay, Rebel Sojourner in the Harlem Renaissance: A Biography. Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

- Locke, Alain, editor. The New Negro: An Interpretation. Albert & Charles Boni, 1925.

Academic Articles

- Davis, M. E. Morris. “Sound and Silence: The Politics of Reading Early Twentieth-Century Lynching Poems.” Canadian Review of American Studies, vol. 48, no. 2, 2018, pp. 211–232.

https://doi.org/10.3138/cras.2017.015 - Abd Allah, Amira Ezz El Din Ahmed. “The Radical Poetry of Claude McKay.” Occasional Papers in the Development of English Education, no. 61, Ain Shams University, June 2016.

https://opde.journals.ekb.eg/article_86132_9f30b51fbb556037cbd9dbec708b4c59.pdf

Website

- “The Lynching Full Text and Analysis.” Owl Eyes.

https://www.owleyes.org/text/lynching