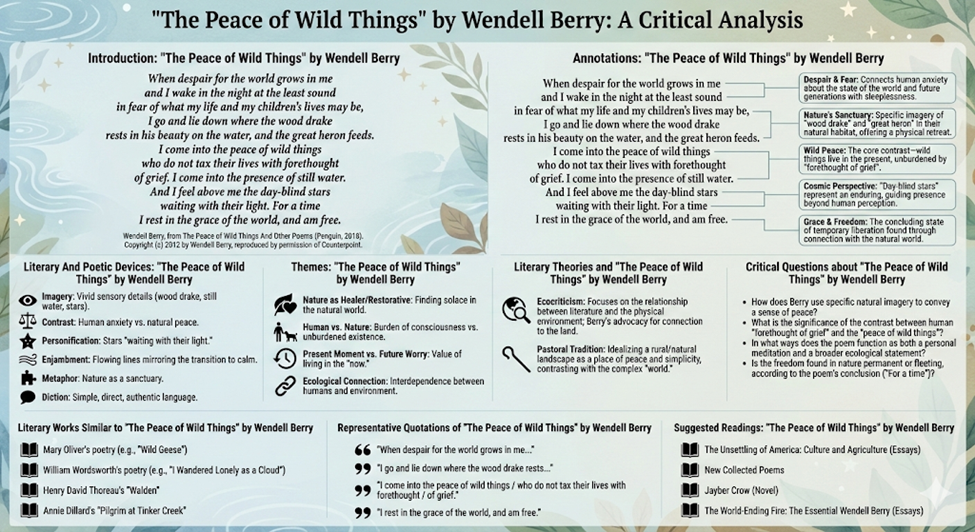

Introduction: “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

“The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry first appeared in 1968 and was later included in his poetry collection The Peace of Wild Things and Other Poems (most recently issued by Penguin in 2018). The poem articulates Berry’s enduring ecological and philosophical vision: a retreat from modern anxiety, political fear, and anticipatory grief into the restorative stillness of the natural world. Written in free verse and a confessional first-person voice, the speaker turns to “wild things” when “despair for the world grows in me,” finding solace among the “wood drake” and the “great heron,” creatures that live without “forethought / of grief.” Central images such as “still water” and the “day-blind stars” emphasize cosmic patience, cyclical time, and a non-anthropocentric order that contrasts sharply with human restlessness. The poem’s popularity lies in its moral clarity and emotional accessibility: it offers nature not as escape but as ethical reorientation, where one may briefly “rest in the grace of the world, and be free.” In an age marked by ecological crisis, political instability, and existential fear, Berry’s quiet affirmation of humility, attention, and peace has made the poem widely anthologized, frequently cited, and deeply resonant with readers seeking spiritual and ecological grounding.

Text: “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

Wendell Berry

from The Peace of Wild Things And Other Poems (Penguin, 2018)

Copyright (c) 2012 by Wendell Berry, reproduced by permission of Counterpoint

Annotations: “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

| Line(s) | Annotation / Meaning | Literary Devices |

| When despair for the world grows in me | The poem opens with global, existential anxiety; “despair” signals moral and ecological crisis rather than personal sadness. | 🔵 Theme (despair, crisis) • 🟢 Diction (abstract noun) • 🟣 Tone (anxious, reflective) |

| and I wake in the night at the least sound | Insomnia reflects heightened fear and psychological unrest; night amplifies vulnerability. | 🔴 Imagery (night, sound) • 🟡 Symbolism (night = fear) • 🟣 Tone |

| in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be, | Fear extends to future generations, foregrounding ethical responsibility and parental anxiety. | 🔵 Theme (future, responsibility) • 🟢 Syntax (expansive clause) • 🟣 Pathos |

| I go and lie down where the wood drake | A deliberate physical and spiritual movement toward nature; “lie down” implies surrender and rest. | 🟠 Motif (retreat) • 🔴 Imagery • 🟢 Contrast (action vs anxiety) |

| rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds. | Animals are portrayed as harmonious and untroubled; nature embodies grace and balance. | 🟡 Pastoral imagery • 🔴 Visual imagery • 🟢 Personification (“beauty”) |

| I come into the peace of wild things | Central thesis: peace is found not in control but in coexistence with the non-human world. | 🔵 Theme (ecological peace) • 🟡 Symbolism (“wild things”) • 🟣 Epiphany |

| who do not tax their lives with forethought | Animals are free from anticipatory anxiety; critique of human overthinking and modern stress. | 🟢 Contrast (human vs animal) • 🔵 Philosophical reflection • 🟣 Didactic tone |

| of grief. | A compressed line emphasizing the burden of human consciousness and projected sorrow. | 🟢 Enjambment • 🔵 Theme (grief) • 🟣 Emphasis through brevity |

| I come into the presence of still water. | Still water symbolizes calm, clarity, and spiritual equilibrium. | 🟡 Symbolism (stillness) • 🔴 Imagery • 🟠 Motif (tranquility) |

| And I feel above me the day-blind stars | Cosmic imagery suggests permanence and order beyond human fear. | 🔴 Celestial imagery • 🟡 Symbolism (stars = endurance) • 🟢 Perspective shift |

| waiting with their light. | Personified stars imply patience and quiet assurance. | 🟢 Personification • 🟣 Tone (reassuring) • 🔵 Theme (cosmic grace) |

| For a time | Acknowledges the temporary nature of peace; realism prevents escapism. | 🟢 Temporal qualifier • 🔵 Philosophical realism |

| I rest in the grace of the world, and am free. | Concluding affirmation: freedom comes through humility and alignment with nature, not mastery over it. | 🔵 Theme (grace, freedom) • 🟡 Metaphor (grace of the world) • 🟣 Resolution |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

| Symbol | Device | Example | Explanation |

| 🔄 | Alliteration | “great heron feeds. / I come into the peace… / presence” | The repetition of sounds (like the ‘h’ or ‘p’) creates a subtle rhythm, although Berry uses this sparingly to maintain a conversational, natural tone. |

| 🗣️ | Assonance | “I lie down,” “life and my children’s lives,” “grace… day” | The repetition of vowel sounds (like the long “i” sound) connects key concepts (life, lying down) and slows the reading pace to match the speaker’s calming state. |

| 🖼️ | Atmosphere (Mood) | Entire poem (shifts from anxious to peaceful) | The poem begins with a mood of “despair” and “fear” but shifts completely to one of “peace,” “grace,” and “freedom” as the speaker enters nature. |

| 🎶 | Consonance | “world,” “children,” “wild,” “feld” (implied in feel/field resonance) | Repetition of consonant sounds (like the ‘ld’ blend) ties the human world of worry to the wild world of peace, bridging the two distinct experiences. |

| ⚖️ | Contrast | “despair for the world” vs. “peace of wild things” | The poem is built on the opposition between human anxiety (future-oriented fear) and nature’s calm (living in the present). |

| 🧱 | Diction (Simple) | “wood drake,” “water,” “stars,” “night” | Berry uses plain, unpretentious language (“Anglo-Saxon” diction) to reflect the simplicity and unadorned truth of the natural world he describes. |

| ⤵️ | Enjambment | “where the wood drake / rests in his beauty” | Breaking the line in the middle of a sentence pulls the reader forward, mimicking the movement of water or the continuous flow of thought. |

| 🏞️ | Imagery (Visual) | “great heron feeds,” “still water,” “day-blind stars” | Vivid mental pictures ground the reader in the physical setting, making the abstract concept of “peace” tangible and concrete. |

| 👁️ | Imagery (Tactile) | “I go and lie down,” “feel above me” | Words that evoke the sense of touch or physical position emphasize the speaker’s bodily connection to the earth, grounded and prone. |

| 🧱 | Juxtaposition | “my life and my children’s lives” vs. “wild things” | Placing complex human concerns next to simple animal existence highlights the “tax” humans pay by worrying about the future. |

| 🧩 | Metaphor | “tax their lives” | Comparing worry to a “tax” suggests that anxiety is a cost or burden that humans pay, draining their resources, whereas animals are exempt from this payment. |

| ⏱️ | Pacing | Stanza structure (one single flow) | The poem is written as a single stanza that moves from a frantic, cluttered opening to a slower, spacious conclusion, mirroring the speaker’s calming breath. |

| 🙎 | Personification | “stars / waiting with their light” | Giving stars the human ability to “wait” implies a patient, benevolent universe that is ready to embrace the speaker whenever they arrive. |

| 📍 | Point of View | “I wake,” “I go,” “I come” | The first-person perspective (“I”) makes the poem a deeply personal confession, inviting the reader to share in the speaker’s private vulnerability. |

| 🔁 | Polysyndeton | “and I wake… and my children’s… and I feel” | The repetition of “and” creates a cumulative effect, first piling up anxieties, then later connecting the peaceful elements of nature. |

| 🌊 | Rhythm (Free Verse) | Entire poem | The lack of a strict rhyme scheme or meter allows the poem to sound like natural speech or a quiet thought process rather than a formal performance. |

| 👂 | Sibilance | “least sound,” “stars,” “rests,” “grace” | The repetition of “s” and soft “c” sounds creates a hushing effect, mimicking the quietness of the woods and the soothing of anxiety. |

| 🏛️ | Structure | Single Stanza | The poem is a single, unbroken block of text, representing a single, complete experience—a journey from one state of mind to another without interruption. |

| 🕊️ | Symbolism | “still water” | Water represents the stillness of the mind and the reflection of reality; it is a mirror that, unlike the human mind, does not distort the world with fear. |

| ⏳ | Temporal Shift | “For a time / I rest” | The phrase “For a time” acknowledges that this peace is temporary; the poem admits that the speaker must eventually return to the world, making the moment of respite more precious. |

Themes: “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

🧠 The Burden of Human Consciousness vs. The Simplicity of Nature

In The Peace of Wild Things, the poet Wendell Berry deftly juxtaposes the heavy, often paralyzing burden of human consciousness with the unencumbered, instinctive existence of the natural world. While the speaker is tormented by an existential dread regarding the uncertain future of his children and the chaotic state of society, the wild creatures he observes—the wood drake and the great heron—exist in a state of pure presence, utterly free from the “forethought of grief” that plagues the human mind. This sharp contrast highlights a fundamental disconnect where humanity’s unique capacity for anticipation and complex reasoning becomes a distinct source of suffering, whereas the animals’ immersion in the immediate moment allows them to retain a dignity and beauty that the anxious speaker envies. By seeking proximity to these creatures, the speaker realizes that the anxiety consuming him is a distinctly human fabrication, a “tax” on his life that can be temporarily shed by realigning himself with the simpler, timeless rhythms of the earth.

🌿 Nature as a Sanctuary for Psychological Restoration

Through the verses of The Peace of Wild Things, Wendell Berry articulates the profound capacity of the natural landscape to serve as a sanctuary for psychological and spiritual restoration when the pressures of the civilized world become overwhelming. The poem suggests that the remedy for a mind besieged by “despair for the world” is not found in intellectual rationalization or further societal engagement, but rather in a physical return to the wild, where one can “lie down” and surrender to the visual and auditory stillness of the water. This act of retreating to the woods is portrayed as a necessary pilgrimage to a holy place, where the “grace of the world” functions as a healing balm that washes away the accumulated grime of modern fear and sleeplessness. Berry posits that nature is not merely a passive backdrop for human activity, but an active, restorative force that offers a tangible, accessible grace to those willing to stillness their own internal chaos and accept the environment’s silent offering of peace.

🌌 The Cosmic Perspective and the Permanence of the Universe

The Peace of Wild Things by Wendell Berry situates the fleeting, often irrational anxieties of the individual human life against the backdrop of an enduring, almost eternal cosmic order represented by the “day-blind stars.” The speaker finds solace not by necessarily solving the specific political or personal problems that cause him to wake in the night, but by widening his perspective to include celestial bodies and natural cycles that have existed long before his fears and will continue long after. The stars, described as “waiting with their light,” imply a universe that is patient, benevolent, and indifferent to human turmoil, offering a sense of stability that contrasts sharply with the volatility of human affairs. By acknowledging that he rests in this grace only “for a time,” Berry accepts the temporary nature of this relief, yet implies that connecting with the timeless elements of the universe provides the strength needed to endure the inevitable return to the complexities of daily life.

👶 Parental Anxiety and the Fear for Future Generations

At the heart of The Peace of Wild Things, Wendell Berry grapples with the specific, gnawing anxiety of parental responsibility and the fear of what an environmentally and politically unstable future holds for the next generation. The poem opens with a confession of deep vulnerability, where the speaker’s dread is not merely for his own safety, but specifically for “what my life and my children’s lives may be,” grounding the abstract concept of despair in a deep, relatable familial love. This fear is presented as a “tax” of the imagination, a projection of potential doom that disrupts the sanctity of the present moment and alienates the speaker from the peace inherent in his immediate surroundings. However, by witnessing the continuity of life in the feeding heron and resting drake, the speaker finds reassurance that the world possesses a resilience and a biological logic that transcends human catastrophic thinking, offering a glimmer of hope that life will persist despite his darkest, late-night premonitions.

Literary Theories and “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

| Literary Theory | Application to Poem | References |

| 🌿 Ecocriticism | Nature as the Antidote to Civilization Ecocritics view this poem as a rejection of anthropocentrism (human-centeredness). The speaker finds that human society (“the world”) is toxic and anxiety-inducing, while the “wild” non-human world offers the only true reality. The poem argues that humans are biologically and spiritually dependent on the biosphere for sanity. It highlights the separation between the human construct of time (worrying about the future) and the ecological reality of the “eternal present.” | • “Despair for the world grows in me” • “I come into the peace of wild things” • “Grace of the world” • “Great heron feeds” |

| 🧠 Psychoanalytic Criticism | The Subconscious and Regression Through this lens, the poem explores the psyche’s response to repressed trauma or anxiety. The “night” represents the unconscious mind where fears manifest (insomnia). The speaker’s retreat to the woods can be seen as a desire to return to a pre-conscious, infantile state—a “womb-like” safety (“lie down,” “water,” “rest”) where the ego is no longer burdened by the complexities of adult responsibility (“forethought of grief”). Nature acts as a therapeutic mechanism to soothe the neurosis of modern life. | • “I wake in the night” • “Fear of what my life… may be” • “Do not tax their lives with forethought” • “I rest in the grace” |

| 💰 Marxist Criticism | Alienation and the “Cost” of Modernity A Marxist reading focuses on the specific word “tax.” It suggests that the speaker is alienated by a capitalist, industrial society that views time and life as commodities to be spent or levied. The “world” that causes despair is likely the socio-political structure. By contrast, the “wild things” exist outside this economic system; they do not pay the “tax” of worry or labor for future profit. The speaker seeks liberation from the oppressive structures of civilized production. | • “Tax their lives with forethought” • “Despair for the world” • “Am free” (implies previous enslavement to the system) |

| 🧘 Existentialism | Angst and the Burden of Consciousness Existentialists would focus on the speaker’s “Angst” (dread)—the uniquely human burden of being aware of one’s own mortality and the uncertainty of the future (“what my life… may be”). The animals are peaceful because they lack this “forethought”; they simply exist. The speaker’s journey is an attempt to overcome existential dread not by denying it, but by engaging with “Being” itself (the stars, the water) to find a moment of authentic freedom in the “now.” | • “Forethought of grief” (Existential anxiety) • “For a time… am free” • “Day-blind stars” (The indifferent universe) • “Waiting with their light” |

Critical Questions about “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

🌿 Question 1: How does the poem construct nature as a moral and psychological refuge rather than mere escapism?

“The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry presents nature not as an escapist fantasy but as a morally instructive space that corrects the excesses of human consciousness. The speaker does not flee responsibility; instead, he seeks temporary recalibration when “despair for the world grows in me,” a despair rooted in ethical concern for the future. By lying down near the wood drake and the great heron, the speaker enters a realm governed by presence rather than projection, where life is not “taxed” by anticipatory grief. Nature functions here as a counter-epistemology: it teaches by example, not by doctrine. The animals’ freedom from forethought exposes the self-imposed burden of modern human anxiety. Importantly, the peace is provisional—“for a time”—which prevents sentimentalization. Berry thus frames nature as a moral refuge that restores clarity and humility, enabling the speaker to re-enter the human world with renewed balance rather than abandoning it altogether.

🌌 Question 2: In what ways does Berry contrast human temporality with cosmic and natural time in the poem?

“The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry establishes a sharp contrast between anxious human temporality and the expansive, non-urgent time of nature and the cosmos. Human time in the poem is future-oriented and burdened by fear, particularly evident in the speaker’s worry about “what my life and my children’s lives may be.” This anticipatory mode of being generates insomnia and psychological unrest. In contrast, natural and cosmic time unfolds in stillness and patience, embodied by the resting wood drake, the feeding heron, and the “day-blind stars” waiting quietly with their light. These images suggest cyclical, enduring time that neither rushes nor anticipates catastrophe. The stars, especially, situate human anxiety within a vast cosmic order that predates and will outlast individual fears. By momentarily aligning himself with this broader temporality, the speaker experiences relief and perspective. Berry thus critiques modern time-consciousness and proposes attentiveness to natural rhythms as a corrective to existential dread.

🧠 Question 3: How does the poem critique human consciousness and rational foresight without rejecting intelligence altogether?

“The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry offers a subtle critique of human rationality, particularly its tendency toward over-anticipation and self-generated suffering, without advocating anti-intellectualism. The phrase “who do not tax their lives with forethought / of grief” identifies foresight as both a uniquely human faculty and a potential burden. Berry does not condemn thinking itself; rather, he questions a mode of consciousness that constantly projects loss and catastrophe, thereby diminishing present life. The animals’ freedom from such forethought is not presented as superiority but as an alternative way of being that exposes human imbalance. By choosing to “come into” their peace, the speaker seeks not to abandon reason permanently but to suspend its anxious excesses. This temporary withdrawal allows for emotional and ethical recalibration. Berry thus argues for a disciplined consciousness—one capable of thought and responsibility, yet grounded in presence, humility, and an acceptance of limits imposed by the natural order.

🌍 Question 4: Why has the poem remained widely popular and relevant in contemporary ecological and social contexts?

“The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry has retained its popularity because it speaks directly to modern conditions of ecological anxiety, political instability, and psychological overload while offering a restrained and credible response. Rather than proposing grand solutions, the poem affirms small, inward acts of attention as ethically meaningful. Its language is accessible yet philosophically rich, allowing readers from diverse backgrounds to recognize their own fears in the speaker’s insomnia and despair. At the same time, the poem resonates strongly with contemporary ecological thought by decentering human dominance and valorizing non-human life as morally instructive. The emphasis on temporary peace—“for a time”—aligns with modern realism, acknowledging that fear and crisis will return. In an era of climate change and collective uncertainty, Berry’s vision of resting “in the grace of the world” offers readers a model of resilience grounded in humility, interdependence, and reverent attention to the natural world.

Literary Works Similar to “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

- 🕊️ “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver: Like Berry’s work, this poem rejects the demand for moral perfection (“You do not have to be good”) and human worry, offering the natural world (“the wild geese, high in the clean blue air”) as a source of redemption and belonging that requires nothing but one’s presence.

- 🌼 “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” by William Wordsworth: Both poems explore the restorative power of nature memory; just as Berry finds peace lying down near the wood drake, Wordsworth’s speaker finds that the memory of dancing daffodils provides “bliss of solitude” when he is in a “vacant or in pensive mood.”

- 🚣 “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” by W.B. Yeats: Yeats’s poem shares Berry’s desire for a physical retreat from the “pavements grey” of civilization to a specific natural sanctuary (“a small cabin build there”), emphasizing the deep, resonant peace that “drops slow” from nature to soothe the troubled human heart.

- 🌲 “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost: While Frost’s ending is more ambiguous regarding duty versus rest, the poem parallels Berry’s in its depiction of a solitary figure pausing in the quiet of the woods to escape societal obligations, finding a magnetic, almost hypnotic peace in the “lovely, dark and deep” silence of the wild.

Representative Quotations of “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

| Quotation | Context in the Poem | Theoretical Perspective & Explanation |

| “When despair for the world grows in me” | Opening line; establishes global, existential anxiety rather than private sorrow. | 🌍 Ecocriticism: Despair is linked to planetary crisis, situating personal emotion within ecological decline rather than isolated psychology. |

| “and I wake in the night at the least sound” | Insomnia signals fear and hyper-awareness caused by modern uncertainty. | 🧠 Existentialism: Anxiety disrupts ordinary being, revealing the fragile condition of human existence under threat. |

| “in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,” | Fear projects into the future and across generations. | ⏳ Ethics of Responsibility: Moral anxiety extends beyond the self, foregrounding intergenerational concern and stewardship. |

| “I go and lie down where the wood drake” | Physical movement toward nature as deliberate choice. | 🌿 Pastoral Retreat: Nature becomes a corrective space, offering withdrawal without permanent escape from society. |

| “rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.” | Animals are shown in harmonious, unselfconscious activity. | 🐦 Biocentrism: Non-human life is valued intrinsically, not as a resource or symbol for human use alone. |

| “I come into the peace of wild things” | Central turning point and thematic core of the poem. | 🌱 Ecocritical Spirituality: Peace is achieved through coexistence, not domination or control of nature. |

| “who do not tax their lives with forethought” | Contrast between animal presence and human overthinking. | 🧩 Critique of Modern Rationality: Excessive foresight becomes psychological labor, undermining well-being. |

| “of grief.” | Isolated line intensifies meaning through brevity. | ✂️ Minimalism & Emphasis: Compression foregrounds grief as a uniquely human burden, sharpened by enjambment. |

| “I come into the presence of still water.” | Speaker reaches a state of calm and attentiveness. | 💧 Symbolism (Pastoral / Spiritual): Still water signifies inner equilibrium and clarity, echoing contemplative traditions. |

| “I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.” | Concluding affirmation; freedom is momentary yet real. | 🕊️ Ecological Humanism: Freedom arises from humility and belonging, not mastery—grace replaces control. |

Suggested Readings: “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry

- Berry, Wendell. The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays of Wendell Berry. Counterpoint, 2003. Counterpoint Press, https://www.counterpointpress.com/books/the-art-of-the-commonplace/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2026.

- Berry, Wendell. The Unsettling of America: Culture & Agriculture. Counterpoint, 2015. Counterpoint Press, https://www.counterpointpress.com/books/the-unsettling-of-america/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2026.

- Cook, Rufus. “Poetry and Place: Wendell Berry’s Ecology of Literature.” The Centennial Review, vol. 40, no. 3, Fall 1996, pp. 503–516. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23740693. Accessed 28 Jan. 2026.

- Cornell, Daniel. “‘The Country of Marriage’: Wendell Berry’s Personal Political Vision.” The Southern Literary Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, Fall 1983, pp. 59–70. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20077720. Accessed 28 Jan. 2026.

- Berry, Wendell. “The Peace of Wild Things.” On Being, 8 Dec. 2016, https://onbeing.org/poetry/the-peace-of-wild-things/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2026.

- Berry, Wendell. “The Peace of Wild Things.” Scottish Poetry Library, https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/peace-wild-things-0/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2026.