Introduction: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

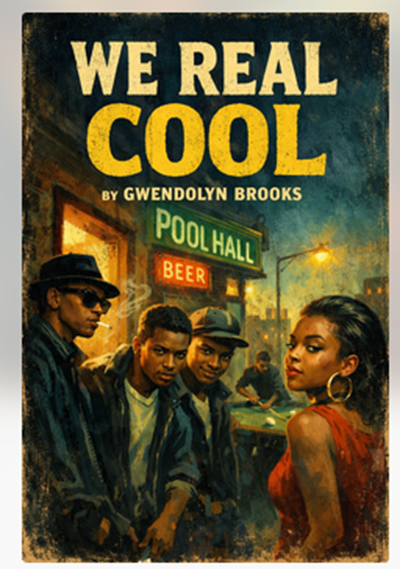

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks first appeared in 1959 in Poetry (September 1959) and was later collected in Brooks’s 1960 volume The Bean Eaters. Framed by the stark scene-setting subtitle—“The Pool Players. / Seven at the Golden Shovel.”—the poem compresses a whole social world into a collective first-person voice whose repeated “We” performs confidence while hinting at fragility. The speakers define “cool” through deliberate refusals and risks—“Left school,” “Lurk late,” “Strike straight,” “Sing sin,” and “Thin gin”—a catalogue of truancy, nocturnal drift, violence, vice, and self-numbing that reads like a set of ritual boasts and defenses. The poem’s main idea is that rebellious identity-making can feel empowering in the moment yet is structurally self-consuming, a tension sealed by the abrupt moral and temporal collapse of the last couplet: “Jazz June. We / Die soon.” Its enduring popularity follows from this exact combination of radical brevity, musical (jazz-like) cadence, and devastating closure: in just a few spare strokes Brooks makes the bravado legible, exposes its costs without sermonizing, and leaves readers with a line that is easy to remember yet difficult to forget.

Text: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

The Pool Players.

Seven at the Golden Shovel.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

Copyright Credit: Gwendolyn Brooks, “We Real Cool” from Selected Poems. Copyright © 1963 by Gwendolyn Brooks. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Gwendolyn Brooks.

Source: Poetry (September 1959)

Annotations: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

| Text | Annotation | Literary devices |

| Legend (how to read devices) | Symbols below identify recurring techniques Brooks uses to create a clipped, “jazz-like” rhythm and a sharp moral turn. | 🔁 Repetition/Epistrophe • ↩️ Enjambment & line-break emphasis • 🎵 End rhyme • 🔤 Sound play (alliteration/assonance/internal rhyme) • 🗣️ Colloquial diction & ellipsis • 🧠 Double entendre • 🕯️ Imagery/Symbolism • 🔮 Foreshadowing • 🎭 Irony/Social critique |

| The Pool Players. | Establishes the speakers as a collective (“players”)—not only pool players, but also risk-takers “playing” with life choices; sets up a choral, group-voice poem. | 🕯️ Framing/setting imagery • 🎭 Social critique (public labeling) |

| Seven at the Golden Shovel. | A precise headcount gives documentary realism; “Golden Shovel” works as a loaded sign: glamour (“Golden”) shadowed by burial (“shovel”), quietly forecasting the end. | 🕯️ Symbolism (place-name) • 🔮 Foreshadowing • 🔤 Emphasis through specificity (“Seven”) |

| We real cool. We | The group self-defines with bravado; the dropped verb (“are”) signals spoken voice; the line break isolates “We,” forcing a pause that turns identity into a beat. | 🔁 Repetition (We) • ↩️ Line-break syncopation • 🗣️ Colloquial diction/ellipsis • 🎭 Irony (boast undercut by context) |

| Left school. We | A blunt confession framed as a badge of honor; ending again on “We” stresses collective responsibility—no one person escapes the group’s choices. | 🔁 Repetition • ↩️ Line-break emphasis • 🎵 End rhyme (cool/school) • 🧩 Parallelism (same sentence pattern) |

| Lurk late. We | “Lurk” shifts the tone from carefree to suspect: secrecy, marginal spaces, and nighttime danger; the clipped phrasing mimics quick, evasive movement. | 🕯️ Imagery (night/streets) • 🔮 Foreshadowing (risk escalates) • 🔤 Sound play (L- onset/harsh consonants) • ↩️ Line-break emphasis |

| Strike straight. We | Can be read literally (accurate pool shots) and figuratively (violence/retaliation); the ambiguity lets “coolness” slide into menace. | 🧠 Double entendre • 🎵 End rhyme (late/straight) • 🔁 Repetition • 🎭 Irony (skill vs harm) |

| Sing sin. We | A tight phrase that fuses pleasure with wrongdoing—celebration replaces conscience; the musical verb (“Sing”) anticipates the later “Jazz.” | 🔤 Sound play (s- repetition) • 🎭 Irony (sin as entertainment) • ↩️ Line-break emphasis • 🕯️ Moral imagery |

| Thin gin. We | Drinking becomes routine; “thin” suggests dilution/cheapness and also bodily/spiritual depletion—pleasure that reduces rather than enriches. | 🔤 Sound play (sin/gin internal echo) • 🕯️ Imagery (alcohol as habit) • 🔮 Foreshadowing (self-wasting) • 🔁 Repetition |

| Jazz June. We | “Jazz” as a verb implies improvisation, speed, and nightlife; “June” hints at youth/summer—brief seasonality that cannot last. | 🔤 Sound play (J- alliteration/assonance) • 🕯️ Seasonal imagery (June = youth) • ↩️ Line-break emphasis • 🎭 Irony (celebration before collapse) |

| Die soon. | The poem snaps shut: no trailing “We,” no lingering rhythm—finality replaces bravado. The earlier “cool” posture is exposed as fragile and short-lived. | 🔮 Foreshadowing fulfilled • 🎵 End rhyme (June/soon) • ⛔ Closure via omission (no final “We”) • 🎭 Irony (boast → mortality) |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

| Device | Short definition | Example from the poem | How it works here |

| 🔴 Alliteration | Repetition of initial consonant sounds | “Lurk late”; “Strike straight” | The repeated sounds create a crisp, percussive beat—like quick cues in a pool hall. |

| 🟠 Anaphora | Repetition at the start of successive phrases/lines | “We real cool. We / Left school. We …” | “We” becomes a chant of group identity, confidence, and self-assertion. |

| 🟡 Assonance | Repetition of vowel sounds | “thin gin” | The tight vowel sound makes the line clipped and dry, reinforcing the sense of depletion. |

| 🟢 Caesura | A deliberate pause within a line | “We real cool. We” | The pause creates a beat-drop; the extra “We” sounds like a posed signature after each claim. |

| 🔵 Colloquialism | Everyday, informal speech | “We real cool.” | The spoken grammar/cadence feels authentic and immediate, fitting youthful bravado. |

| 🟣 Consonance | Repetition of consonant sounds (often at line ends) | “sin / gin”; “June / soon” | The shared end-sounds bind the poem tightly and add a closing-in musicality. |

| 🟤 Diction | Word choice and its effect | “Left,” “Lurk,” “Strike,” “Thin,” “Die” | Mostly blunt one-syllable verbs: hard-edged action that hints at hard consequences. |

| ⚫ Ellipsis (omission) | Leaving out words that are understood | “We real cool” (omits “are”) | The omission speeds the line and performs “cool,” while subtly signaling instability beneath the pose. |

| ⚪ Enjambment | Meaning runs over a line break | “We real cool. We / Left school. We” | The carry-over keeps momentum and restlessness, while each “We” resets the stance. |

| 🟥 End-stopped line | A line ending with punctuation/complete thought | “We real cool. We” | Short, snapped statements feel like boasts delivered as finished facts. |

| 🟧 Epigram | Brief, memorable poem with a sharp point | “Jazz June. We / Die soon.” | The ending lands like a proverb—compact, quotable, and devastating. |

| 🟨 Imagery | Concrete detail that evokes a scene | “Seven at the Golden Shovel.” | A vivid place-name anchors the speakers in a specific social space and mood. |

| 🟩 Irony | Contrast between surface meaning and deeper meaning | “We real cool.” → “Die soon.” | The swagger of “cool” is undercut by the ending; freedom flips into self-destruction. |

| 🟦 Minimalism | Extreme brevity and spareness | Very short lines; few adjectives | The stripped style intensifies the voice and amplifies the final warning. |

| 🟪 Parallelism | Repeated grammatical structures | “Lurk late. We / Strike straight. We / Sing sin. We” | The repeated pattern suggests a routine—choices becoming a cycle. |

| ♦️ Refrain | Repeated line/phrase across the poem | Recurring “We” | Like a chorus, “We” reinforces solidarity while sounding like continual self-justification. |

| ♣️ Rhyme (full/near) | Sound correspondence at line ends | “cool/school,” “sin/gin,” “June/soon” | The rhyme makes the poem musical and memorable; the neatness contrasts with messy lives. |

| ♥️ Rhythm (syncopation) | Pattern of beats/stresses | “We real cool. We” (beat-like phrasing) | The cadence mimics jazz riffs—short, syncopated bursts that perform style and bravado. |

| 💠 Synecdoche | A part stands for a whole | “Seven at the Golden Shovel.” | The seven voices represent a wider youth experience, condensed into one collective “We.” |

| ⭐ Volta (turn) | A shift in tone/meaning, often near the end | Turn into “Die soon.” | The poem pivots from defiance to mortality, converting swagger into warning. |

Themes: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

- 🔷 Performative “Cool” and Collective Identity

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks presents “coolness” as a performed group identity, because the repeated “We” functions like a chant that asserts solidarity while simultaneously revealing how fragile that solidarity is. When the speakers declare, “We real cool. We / Left school. We,” the compressed grammar and abrupt pauses create a voice that sounds confident, yet the relentless return to the collective pronoun suggests they must keep re-declaring themselves to keep uncertainty at bay. The poem’s tight, slogan-like statements operate as public self-fashioning, as though the seven players at “the Golden Shovel” can become a single persona by speaking in unison. At the same time, the chorus flattens individuality and implies that belonging requires adopting the same risky script, so that identity is gained through membership but purchased at the cost of personal depth and sustained possibility. In this way, the poem shows collective swagger as both protection and self-erasure. - 🟥 Rebellion, Truancy, and Defiance of Institutions

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks frames youthful rebellion as both an act of will and a symptom of exclusion, since the poem’s proud declarations—“Left school,” “Lurk late”—stage refusal as freedom even while implying that conventional routes to recognition may already feel blocked. By placing “Left school” so early, Brooks makes institutional rejection the foundation of the speakers’ self-definition, and by pairing it with nocturnal drifting she suggests that, once stabilizing structures are abandoned, time itself becomes unregulated and precarious. The poem’s minimal, one-syllable verbs read like a list of deliberate choices, yet their accumulation feels less like open possibility and more like narrowing options, as if defiance is the only language left to young men who have learned that compliance does not guarantee belonging. The result is a portrait of rebellion that is posture and protest at once, but also a drift into consequences the speakers refuse to name directly. - 🟩 Risk Culture, Violence, and Self-Destructive Pleasure

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks maps a risk culture in which pleasure, danger, and status reinforce one another, because the speakers bind identity to acts that court harm: “Strike straight,” “Sing sin,” “Thin gin.” “Strike straight” can signal both skill and aggression, so the poem keeps violence hovering without specifying a target, and that ambiguity mirrors how normalized threat can become within a peer code that prizes hardness. Likewise, “Sing sin” converts wrongdoing into performance, implying that transgression is not merely committed but showcased, while “Thin gin” reduces intoxication to an image of depletion, as though the very substance meant to fortify them instead erodes them. Even “Jazz June,” with its brightness and music, reads like a brief seasonal flare—an aestheticized present that intensifies the moment but cannot extend it. The poem therefore links hedonism to erosion, suggesting that “cool” is maintained only by repeatedly courting what will undo it. - 🟣 Foreshortened Futures and the Shock of Mortality

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks delivers its central warning through an ending that is musically inevitable yet morally startling, because “Jazz June. We / Die soon.” collapses pleasure into death with almost no transition, forcing the reader to feel how quickly a life can move from pose to silence. “Die soon” is not argued for; it is asserted, and that bluntness suggests a social reality in which early death is less an abstract risk than a known horizon for the “Seven” whose days are organized around lurking, striking, sinning, and drinking. By withholding explanation, Brooks avoids sermonizing, yet the final couplet retrospectively darkens every earlier boast, so that the poem’s rhythms begin to sound like a countdown rather than a celebration. Mortality here is not merely biological; it is structural and social, implying that certain lives are granted intensity in the present precisely because the future has been quietly foreclosed.

Literary Theories and “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

| Literary theory (theory in same cell) | Core lens (what it asks) | Poem references (quoted phrases) | Theory-based reading (applied to We Real Cool) |

| 🏛️ New Criticism / Formalism | How do form, sound, and structure produce meaning? | “We … We …”; “cool/school,” “late/straight,” “sin/gin,” “June/soon”; the missing final “We” after “Die soon.” | The poem’s tight couplets, end rhymes, and repeated “We” create a chant-like rhythm that mimics bravado. The line breaks make “We” a percussive beat—identity performed, not explained. The formal shock is the last line: by withholding “We” at the end, Brooks converts group swagger into abrupt finality, making mortality the poem’s decisive “closure.” |

| 🧩 Structuralism (Binary oppositions) | What oppositions and social codes structure meaning? | “cool” vs “school”; “lurk late” vs social respectability; “sing sin” vs moral order; “Jazz June” vs “Die soon.” | The poem is built on binaries: institutional order (school) versus street code (cool); visibility versus lurking; life/season (June) versus death (soon). The “We” functions as a collective sign (a group identity produced by shared behaviors), while the Golden Shovel setting codes the speakers into a recognizable cultural script of rebellion that leads to predictable social outcomes. |

| 💼 Marxist / Cultural Materialism | How do class, labor, institutions, and ideology shape lives? Who benefits from the social order? | “Left school”; “lurk late”; “Thin gin”; “Seven at the Golden Shovel.” | The poem can be read as a snapshot of marginalized youth positioned outside the pathways of social mobility (signaled by “Left school”). Leisure (pool hall) is not “free” but shaped by material constraint: limited access to secure work and education fosters alternative status economies (“cool”). “Thin gin” hints at cheap consumption and scarcity. The fatal ending underscores how a classed social environment can convert youthful defiance into shortened life chances. |

| 🧬 Critical Race Theory / African American Studies | How do race and power structure representation, space, and “respectability” narratives? | “The Pool Players”; “Seven at the Golden Shovel”; repeated “We”; “Die soon.” | Read as a racialized urban micro-scene, the poem refuses an outsider’s moral lecture and instead offers an inside, collective voice (“We”) that performs “cool” as both style and survival. The pool hall becomes a racialized social space where identity is negotiated under surveillance and stereotype. The ending—“Die soon”—can be read as an indictment of structural conditions that render Black youth disproportionately vulnerable (social risk, institutional abandonment, and constrained futures), even as the poem preserves their voice with dignity and precision. |

Critical Questions about “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

- 🔍 Critical Question 1: How does the poem’s repeated “We” shape our understanding of identity and responsibility?

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks uses the recurring “We” to construct a collective persona that feels confident, rhythmic, and unified, yet the same chorus also complicates responsibility by dispersing it across the group. Because each statement is immediately followed by “We,” the voice reads like a practiced performance, as though the speakers are continuously affirming that they belong and that their choices are shared rather than individual. This collective framing can be read as protective, since it offers solidarity within a marginal space (“Seven at the Golden Shovel”), but it can also be read as evasive, because the group voice allows any single speaker to hide behind the plural and to treat risky actions—“Left school,” “Thin gin”—as badges of membership rather than personal decisions with personal consequences. In this way, Brooks turns a simple pronoun into a moral instrument, showing how identity can be built through community while accountability is quietly diluted. - 🧩 Critical Question 2: Does the poem criticize the speakers, sympathize with them, or do both at once?

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks achieves its sharpest effect by refusing a single, settled posture toward the speakers, because the poem simultaneously records their bravado with lyrical precision and exposes how that bravado collapses into vulnerability. On one level, the clipped, musical lines honor the speakers’ style—“Lurk late,” “Strike straight,” “Jazz June”—and the voice sounds self-possessed, even charismatic, which can draw the reader into a momentary admiration of their “cool.” Yet the sequence of verbs steadily accumulates into a portrait of narrowing options, and the final turn—“Die soon”—reframes the earlier swagger as a tragic performance staged against a foreshortened future. Brooks therefore critiques the culture of risk and self-harm without turning the speakers into mere objects of blame, since the poem’s restraint and lack of moralizing invite the reader to ask what social conditions make such a script feel desirable, available, or inevitable. The poem thus holds judgment and empathy in productive tension. - 🎷 Critical Question 3: What is the relationship between the poem’s musicality and its message about time, pleasure, and consequence?

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks makes musicality do ethical work, because the poem’s syncopated brevity resembles jazz riffing—quick bursts, sharp stops, and repeated motifs—while the content narrates a lifestyle built on speed, sensation, and improvisation. Each compact phrase lands like a beat, and the repeated “We” functions as a refrain that keeps the voice moving forward, so the reader experiences momentum even as the poem offers almost no narrative explanation. That musical propulsion mirrors the speakers’ logic of the present: they “Lurk late,” “Sing sin,” and “Thin gin” as if the night is endless, while the poem’s rapid pacing suggests, ironically, how fast the consequences arrive. When Brooks writes “Jazz June,” she concentrates pleasure into a bright, seasonal instant, and by placing “Die soon” immediately after, she turns the rhythm into a kind of countdown, where style accelerates the approach of loss. The poem’s sound, therefore, is not decorative; it is the mechanism through which fleeting pleasure and shortened time are felt. - ⚖️ Critical Question 4: How does the poem invite a social reading of marginalization without explicitly stating social facts?

“We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks implies a dense social context through strategic minimalism, because it offers only a location marker—“The Pool Players. / Seven at the Golden Shovel.”—and then lets the speakers’ declarations disclose the pressures and limits shaping their lives. By naming a specific gathering place, the poem situates the speakers in a public yet marginal space where leisure becomes identity, and by foregrounding “Left school,” it signals a break with institutional pathways that typically structure mobility and recognition. The poem never supplies background on poverty, race, or neighborhood conditions, yet the condensed list of actions—lurking, striking, drinking—reads like a familiar survival script associated with restricted opportunity and peer-coded prestige. Importantly, Brooks avoids overt sociological explanation, and this restraint prevents the poem from flattening the speakers into case studies; instead, it compels the reader to infer the social forces that make “cool” feel necessary and danger feel normal. The closing “Die soon” then operates as a structural indictment, suggesting that premature endings are not only personal outcomes but also social patterns.

Literary Works Similar to “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

- 🔷 “Harlem” by Langston Hughes — Like Brooks, it uses compressed, musical phrasing to expose how social pressure and blocked futures can turn youthful energy into danger and loss.

- 🟥 “Ballad of Birmingham” by Dudley Randall — Similar in its plainspoken clarity and moral punch, it confronts the vulnerability of Black youth and ends with a stark, unforgettable finality.

- 🟩 “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar — Like We Real Cool, it relies on a collective “we” voice to show identity as performance under social constraint, with irony beneath the surface.

- 🟨 “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” by Gil Scott-Heron — Comparable for its beat-driven cadence and cultural critique, using rhythmic repetition and street-register language to indict the realities surrounding Black life.

Representative Quotations of “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical perspective |

| 🔹 “We real cool.” | Context: The poem opens in a collective first-person voice, establishing a public pose of confidence that will govern every subsequent claim. | Theoretical perspective: Performative identity (cultural studies/discourse) — “cool” functions as a social performance; the assertion sounds like self-creation through speech, yet its insistence hints that the identity must be repeatedly staged to remain credible. |

| 🟦 “We / Left school.” | Context: Early placement makes withdrawal from institutional schooling the foundation of the group’s self-definition and social stance. | Theoretical perspective: Marxist / cultural materialist reading — the line can be read as a refusal of dominant mobility scripts, while also registering how classed institutions distribute opportunity unevenly, making “leaving” both choice and symptom of structural constraint. |

| 🟩 “We / Lurk late.” | Context: The speakers align themselves with nighttime, secrecy, and a rhythm of life outside regulated schedules and surveillance. | Theoretical perspective: Spatial theory (urban/liminal space) — “late” marks a liminal temporal zone where marginal identities consolidate; the poem suggests how belonging is produced in edges (night, street, pool hall) rather than in sanctioned daytime spaces. |

| 🟥 “We / Strike straight.” | Context: The phrase implies precision and hardness; it can gesture to pool skill while keeping aggression and threat suggestively present. | Theoretical perspective: Masculinity studies / subcultural capital — “straight” striking reads as competence coded as toughness; credibility is earned through displays of control and force, which become currencies inside the peer group. |

| 🟨 “We / Sing sin.” | Context: Transgression becomes celebratory and communal, as if wrongdoing is converted into music and identity rather than guilt. | Theoretical perspective: Psychoanalytic (defense and desire) — turning “sin” into “song” aestheticizes forbidden desire, functioning as a defense mechanism that transforms moral anxiety into performance and pleasure. |

| 🟪 “We / Thin gin.” | Context: The poem compresses substance use into two clipped words, suggesting both indulgence and depletion (body, judgment, future). | Theoretical perspective: Critical public-health / social realism — “thin” implies erosion; the line can be read as a minimal social document of self-medicating under pressure, where coping practices accelerate harm. |

| 🎷 “We / Jazz June.” | Context: The diction brightens; “June” evokes youth, summer, and possibility, while “jazz” implies improvisation, style, and speed. | Theoretical perspective: Formalist (sound-and-structure) with modernist aesthetics — the poem’s musical economy peaks here; the line dramatizes how style becomes a way to seize the present, compressing life into a vivid, performative moment. |

| ⚫ “We / Die soon.” | Context: The closing couplet abruptly collapses bravado into mortality, turning the preceding boasts into a foreshortened life narrative. | Theoretical perspective: Existential / tragic realism — the poem confronts finitude without explanation or moralizing; the bluntness makes death feel not merely personal but predictable within the speakers’ chosen (and socially conditioned) script. |

| 🟠 “The Pool Players.” | Context: The subtitle frames the speakers as a recognizable social group gathered around leisure, risk, and display, before the “We” voice even begins. | Theoretical perspective: Reader-response / framing theory — the label guides interpretation by priming expectations about youth culture and social judgment; the poem then complicates that expectation by giving the group a seductive, self-authored voice. |

| 🟤 “Seven at the Golden Shovel.” | Context: A precise number and a named place create a vivid micro-scene: a small cohort in a specific social space with its own codes of belonging. | Theoretical perspective: New Historicist / cultural studies (microhistory) — the detail anchors the poem in lived social geography; the localized “Golden Shovel” becomes a symbol of how everyday sites produce identity, ritual, and fate. |

Suggested Readings: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

Books

- Brooks, Gwendolyn. The Bean Eaters. Harper, 1960.

- Mootry, Maria, and Gary Smith, editors. A Life Distilled: Gwendolyn Brooks, Her Poetry and Fiction. University of Illinois Press, 1987.

Academic articles

- Lockhart, James. “We Real Cool”: Dialect in the Middle-School Classroom.” English Journal, vol. 80, no. 8, Dec. 1991, pp. 53–58. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej19918206. Accessed 29 Dec. 2025.

- Sih, Emmerencia Beh. “A Postcolonial Reading of D.H Lawrence ‘Snake’ and Gwendolyn Brooks ‘We Real Cool’.” The Creative Launcher, vol. 5, no. 5, 30 Dec. 2020, pp. 36–42. https://doi.org/10.53032/tcl.2020.5.5.04. Accessed 29 Dec. 2025.

Poem websites

- Brooks, Gwendolyn. “We Real Cool.” Poetry Foundation (Poetry magazine archive). https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/28112/we-real-cool. Accessed 29 Dec. 2025.

- Brooks, Gwendolyn. “We Real Cool.” Poets.org (Academy of American Poets). https://poets.org/poem/we-real-cool. Accessed 29 Dec. 2025.