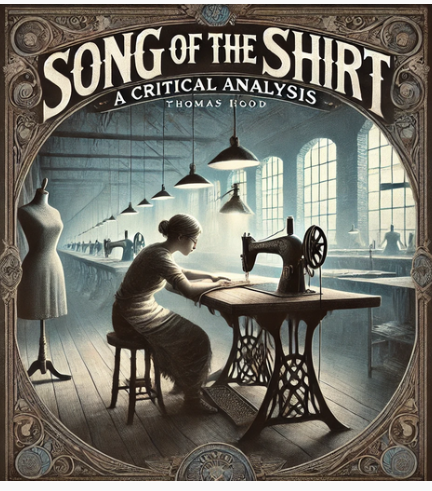

Introduction: “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

“Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood, first appeared in 1843 in the satirical magazine Punch, became an emblematic piece of social commentary, addressing the dire working conditions of seamstresses in Victorian England. Its main themes include poverty, exploitation, and the dehumanizing effects of unrelenting labor. Hood vividly portrays the physical and emotional toll of ceaseless toil, encapsulated in the repetitive refrain “Work! work! work!” The poem’s striking imagery and evocative language highlighted the plight of the working poor, particularly women, and it resonated with contemporary audiences, stirring public empathy and calls for reform. Its enduring popularity as a textbook poem lies in its powerful narrative style, rhythmic repetition, and its ability to elicit moral reflection on social injustice, making it a compelling piece for educational exploration of Victorian literature and social history.

Text: “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

With fingers weary and worn,

With eyelids heavy and red,

A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

Plying her needle and thread—

Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch

She sang the “Song of the Shirt.”

“Work! work! work!

While the cock is crowing aloof!

And work—work—work,

Till the stars shine through the roof!

It’s O! to be a slave

Along with the barbarous Turk,

Where woman has never a soul to save,

If this is Christian work!

“Work—work—work,

Till the brain begins to swim;

Work—work—work,

Till the eyes are heavy and dim!

Seam, and gusset, and band,

Band, and gusset, and seam,

Till over the buttons I fall asleep,

And sew them on in a dream!

“O, men, with sisters dear!

O, men, with mothers and wives!

It is not linen you’re wearing out,

But human creatures’ lives!

Stitch—stitch—stitch,

In poverty, hunger and dirt,

Sewing at once, with a double thread,

A Shroud as well as a Shirt.

“But why do I talk of death?

That phantom of grisly bone,

I hardly fear his terrible shape,

It seems so like my own—

It seems so like my own,

Because of the fasts I keep;

Oh, God! that bread should be so dear.

And flesh and blood so cheap!

“Work—work—work!

My labour never flags;

And what are its wages? A bed of straw,

A crust of bread—and rags.

That shattered roof—this naked floor—

A table—a broken chair—

And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank

For sometimes falling there!

“Work—work—work!

From weary chime to chime,

Work—work—work,

As prisoners work for crime!

Band, and gusset, and seam,

Seam, and gusset, and band,

Till the heart is sick, and the brain benumbed,

As well as the weary hand.

“Work—work—work,

In the dull December light,

And work—work—work,

When the weather is warm and bright—

While underneath the eaves

The brooding swallows cling

As if to show me their sunny backs

And twit me with the spring.

“O! but to breathe the breath

Of the cowslip and primrose sweet—

With the sky above my head,

And the grass beneath my feet;

For only one short hour

To feel as I used to feel,

Before I knew the woes of want

And the walk that costs a meal!

“O! but for one short hour!

A respite however brief!

No blessed leisure for Love or hope,

But only time for grief!

A little weeping would ease my heart,

But in their briny bed

My tears must stop, for every drop

Hinders needle and thread!”

With fingers weary and worn,

With eyelids heavy and red,

A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

Plying her needle and thread—

Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch,—

Would that its tone could reach the Rich!—

She sang this “Song of the Shirt!”

Annotations: “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

| Stanza | Content Summary | Themes/Imagery | Annotations |

| 1 | Introduces the woman, weary and worn, working tirelessly with her needle and thread amidst poverty, hunger, and dirt. | Despair, physical exhaustion, dehumanization. | The woman’s weariness symbolizes the relentless labor of the poor. Her “unwomanly rags” highlight the loss of dignity and femininity due to poverty. The repetitive “stitch! stitch! stitch!” mimics her monotonous work. |

| 2 | Describes unending labor from dawn until nightfall, comparing her plight to slavery and lamenting the cruelty of “Christian work.” | Critique of societal hypocrisy, endless toil. | The stanza contrasts Christian values with the inhumane treatment of workers, suggesting irony in her comparison to being a slave under a “barbarous Turk.” Hood critiques industrial exploitation cloaked in morality. |

| 3 | Recounts the physical toll of work—fatigue and dreaming of stitching even in her sleep. | Repetition, physical degradation. | The repetition of “work” and “seam, and gusset, and band” underscores the monotony. Her dreams of sewing indicate the all-encompassing nature of her work, showing how it invades her mind and rest. |

| 4 | Appeals to men with family connections to recognize that their clothing is made at the cost of human lives. | Emotional appeal, moral responsibility. | Hood appeals directly to male readers, emphasizing their connection to women (mothers, wives, sisters) to inspire empathy and reform. The metaphor of sewing a “Shroud as well as a Shirt” underscores the life-threatening labor. |

| 5 | Discusses her familiarity with death, noting it feels like her own due to starvation and suffering. | Death, starvation, physical decay. | The grim personification of death highlights her desensitization to it. The line “bread should be so dear, and flesh and blood so cheap” is a powerful critique of societal priorities and systemic neglect of human welfare. |

| 6 | Describes the meager wages and living conditions she endures—poverty is all-consuming. | Poverty, despair, minimal subsistence. | The description of her home (a shattered roof, broken chair) paints a vivid picture of extreme poverty. Even her shadow on a blank wall offers companionship, symbolizing her isolation and lack of comfort. |

| 7 | Emphasizes the monotony of work, likening her labor to that of prisoners and showing its mental and physical toll. | Monotony, dehumanization, numbness. | Comparing her work to a prisoner’s punishment reflects the lack of agency and autonomy. Her brain is “benumbed,” reflecting the mental exhaustion from her endless cycle of labor. |

| 8 | Notes that she works regardless of the seasons, envying the freedom and joy of birds. | Loss of connection to nature, unchanging hardship. | The swallows mocking her with their sunny backs symbolize freedom and the natural rhythms of life, which are inaccessible to her. This stanza contrasts her constrained existence with the liberty of nature. |

| 9 | Expresses a longing for even a brief respite, recalling a time when she was free from poverty and want. | Nostalgia, yearning, loss of joy. | Her yearning for “one short hour” of freedom underscores her deep suffering and the absence of basic human pleasures. Her longing is not for wealth but for peace, symbolizing the intensity of her deprivation. |

| 10 | Concludes with her continued labor, lamenting her inability to grieve or express emotions due to the demands of work. | Suppression of emotions, relentless hardship. | Tears are a luxury she cannot afford because they disrupt her work, a powerful symbol of how poverty suppresses humanity. The stanza circles back to the relentless “needle and thread,” completing the cycle of her drudgery. |

| 11 | Returns to the opening image of the woman, emphasizing her worn state and plea for the rich to hear her plight. | Final appeal, critique of inequality. | The repetition of the opening image and the line “Would that its tone could reach the Rich!” reinforces the central message of social critique, calling attention to the disconnect between the wealthy and the working poor. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

| Device | Example | Explanation |

| Alliteration | “With fingers weary and worn” | Repetition of the “w” sound emphasizes the woman’s exhaustion. |

| Allusion | “Along with the barbarous Turk” | Refers to the stereotype of harsh slavery under Turks, contrasting it with Victorian labor conditions. |

| Anaphora | “Work! work! work!” | Repetition at the beginning of lines reinforces the monotonous labor. |

| Apostrophe | “O, men, with sisters dear!” | Direct address to men appeals to their empathy and moral responsibility. |

| Assonance | “Till the brain begins to swim” | Repetition of the “i” sound creates a rhythmic effect mimicking weariness. |

| Caesura | “My labour never flags; / And what are its wages? A bed of straw” | A pause within the line mirrors the breaking point of the speaker’s patience. |

| Contrast | “Bread should be so dear, / And flesh and blood so cheap!” | Highlights the disparity between the value of basic needs and human lives. |

| Diction | “In poverty, hunger, and dirt” | The choice of stark, negative words emphasizes the dire conditions. |

| End Rhyme | “With fingers weary and worn, / With eyelids heavy and red” | Regular rhyme scheme adds to the musicality and memorability of the poem. |

| Enjambment | “Sewing at once, with a double thread, / A Shroud as well as a Shirt” | The continuation of the sentence into the next line emphasizes the interconnectedness of death and labor. |

| Epistrophe | “Seam, and gusset, and band, / Band, and gusset, and seam” | Repetition at the end of phrases mirrors the repetitive nature of the work. |

| Hyperbole | “Till over the buttons I fall asleep, / And sew them on in a dream!” | Exaggeration emphasizes the all-consuming nature of her labor. |

| Imagery | “A bed of straw, / A crust of bread—and rags” | Vivid descriptions paint a picture of the woman’s impoverished living conditions. |

| Irony | “If this is Christian work!” | Highlights the hypocrisy of a society claiming Christian values while exploiting workers. |

| Metaphor | “Sewing at once, with a double thread, / A Shroud as well as a Shirt” | The shirt becomes a metaphor for death, symbolizing the fatal cost of her labor. |

| Onomatopoeia | “Stitch! stitch! stitch!” | Mimics the sound of sewing, adding a sensory dimension to the monotony. |

| Paradox | “No blessed leisure for Love or hope, / But only time for grief!” | Highlights the contradiction in having time only for suffering, not for relief or joy. |

| Personification | “That phantom of grisly bone” | Death is given human characteristics, making it a familiar and almost relatable figure to the speaker. |

| Repetition | “Work—work—work” | Repetition emphasizes the relentless and unending nature of her labor. |

| Tone | “Would that its tone could reach the Rich!” | The tone is a mix of despair and plea, aiming to evoke empathy and social awareness from the audience. |

Themes: “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

1. Exploitation and Dehumanization of Labor

The central theme of “Song of the Shirt” is the exploitation and dehumanization of laborers, particularly working-class women. Hood vividly portrays the endless toil of a seamstress, emphasizing how relentless labor strips her of her humanity. Lines such as “Work! work! work! / Till the brain begins to swim; / Work! work! work, / Till the eyes are heavy and dim!” underscore the physical and mental toll of repetitive, unyielding work. The monotonous refrain “stitch! stitch! stitch!” mimics the mechanical, dehumanizing rhythm of her labor, making her existence seem like that of a mere tool in the service of others.

2. Poverty and Social Injustice

The poem highlights the severe poverty and social injustice experienced by Victorian workers. The speaker’s lament, “It is not linen you’re wearing out, / But human creatures’ lives!” directly critiques the upper-class consumers who benefit from her labor without acknowledging its human cost. Her description of her living conditions—“A bed of straw, / A crust of bread—and rags”—paints a grim picture of destitution, contrasting starkly with the comfort of those who exploit her. Hood uses this disparity to expose the moral failures of a society that allows such suffering to persist.

3. Hypocrisy of Christian Morality

Hood critiques the hypocrisy of a society that professes Christian values while perpetuating systems of oppression and poverty. The line, “If this is Christian work!” reflects the speaker’s bitter irony, as the exploitation she endures contradicts the principles of compassion and charity central to Christianity. This theme is further reinforced through the metaphorical comparison of her plight to slavery: “It’s O! to be a slave / Along with the barbarous Turk,” contrasting so-called “barbaric” cultures with the ostensibly moral Victorian society.

4. Longing for Freedom and Natural Beauty

The speaker yearns for freedom and a return to the natural world, which stands in stark contrast to her oppressive reality. Her wistful desire, “O! but to breathe the breath / Of the cowslip and primrose sweet,” reflects her longing for an escape from industrial drudgery into the peaceful simplicity of nature. However, the monotonous refrain of “work—work—work” serves as a reminder of her inability to break free, symbolizing how industrial labor suppresses individuality and connection to the natural world. This theme adds a poignant layer of emotional depth to the poem.

Literary Theories and “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

| Literary Theory | Explanation | Application to “Song of the Shirt” |

| Marxist Literary Theory | Focuses on class struggle, labor exploitation, and economic inequality in literature. | The poem critiques the capitalist system that exploits workers for profit. Lines such as “It is not linen you’re wearing out, / But human creatures’ lives!” expose the dehumanizing effects of industrial labor and highlight the stark disparity between the wealthy and the working poor. Hood’s portrayal of the seamstress reflects the alienation and oppression central to Marxist critique. |

| Feminist Literary Theory | Examines the roles, oppression, and representation of women in literature and society. | Hood highlights the unique suffering of working-class women, evident in the description of the seamstress’s plight: “A woman sat in unwomanly rags.” The phrase “unwomanly rags” signals the loss of femininity and dignity under harsh labor conditions, while the direct appeal to men (“O, men, with mothers and wives!”) underscores the gendered dimension of societal exploitation. |

| Formalism/New Criticism | Focuses on the structure, form, and use of literary devices within the text itself, rather than external context. | The repetition of “work! work! work!” and “stitch! stitch! stitch!” exemplifies the formalist focus on sound and structure to convey meaning. The poem’s rhythm and rhyme mimic the monotony of labor, while devices such as alliteration (“fingers weary and worn”) and imagery (“A bed of straw, / A crust of bread—and rags”) create a vivid and poignant experience for the reader, highlighting its craftsmanship. |

Critical Questions about “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

1. How does Hood use repetition to emphasize the theme of monotonous labor?

Hood employs repetition throughout the poem to mirror the unrelenting monotony of the seamstress’s labor. The recurring phrases “Work! work! work!” and “Stitch! stitch! stitch!” not only reflect the physical act of sewing but also the oppressive, cyclical nature of her life. This repetition creates a rhythmic cadence that mimics the repetitive actions of her work, reinforcing the exhaustion and lack of escape in her existence. The stanza “Seam, and gusset, and band, / Band, and gusset, and seam” exemplifies this device, as the repetition mirrors the routine nature of her tasks, making the reader feel the weariness of her ceaseless toil.

2. How does the poem critique societal inequality?

Hood’s critique of societal inequality is most evident in his depiction of the contrast between the laboring poor and the wealthy who benefit from their work. The line “It is not linen you’re wearing out, / But human creatures’ lives!” directly accuses the rich of exploiting workers without regard for their suffering. By addressing “men, with mothers and wives,” Hood appeals to the readers’ emotions, urging them to recognize the humanity of laborers. The seamstress’s impoverished conditions—“A bed of straw, / A crust of bread—and rags”—serve as a stark contrast to the comfort of the affluent, exposing the moral failing of a society that tolerates such disparity.

3. In what ways does the poem highlight the gendered nature of labor?

The poem underscores the gendered aspect of labor by focusing on the plight of a working-class woman. Hood describes her sitting “in unwomanly rags,” a phrase that highlights how poverty and exploitation strip her of traditional femininity and dignity. Her plea, “O, men, with sisters dear! / O, men, with mothers and wives!” emphasizes that women’s suffering is tied to the roles they fulfill within families, calling on men to empathize with their female relatives. Additionally, the imagery of her sewing “a Shroud as well as a Shirt” underscores the deadly intersection of labor and gender, suggesting that the domestic and societal expectations placed on women lead to their physical and emotional demise.

4. What role does nature play in the poem, and what does it signify?

Nature serves as a symbol of freedom and a stark contrast to the seamstress’s oppressive reality. Her yearning “to breathe the breath / Of the cowslip and primrose sweet” represents an escape from the constraints of industrial labor into a world of simplicity and peace. The imagery of “the brooding swallows” clinging beneath the eaves highlights her entrapment, as even the birds’ freedom mocks her confinement. By juxtaposing the natural world with the grimness of her work, Hood underscores the unnaturalness of her suffering, suggesting that such labor alienates her from life’s inherent joys and freedoms.

Literary Works Similar to “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

- “The Cry of the Children” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Explores the exploitation of child labor during the Industrial Revolution, similar to Hood’s focus on the suffering of laborers. - “London” by William Blake

Critiques the social injustices and moral decay of urban life, paralleling Hood’s condemnation of societal inequality. - “The Charge of the Light Brigade” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Though about war, it shares Hood’s use of repetition and rhythm to emphasize relentless human toil and sacrifice. - “To a Mouse” by Robert Burns

Reflects on human and animal suffering caused by societal systems, resonating with Hood’s empathy for the downtrodden. - “A Worker Reads History” by Bertolt Brecht

Questions the invisibility of the laboring class in historical narratives, aligning with Hood’s focus on the seamstress’s unacknowledged suffering.

Representative Quotations of “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

| Quotation | Context | Theoretical Perspective |

| “With fingers weary and worn, / With eyelids heavy and red” | Introduces the seamstress, highlighting her physical exhaustion from relentless labor. | Marxist Theory: Reflects the dehumanizing impact of industrial labor on the working class. |

| “Stitch! stitch! stitch! / In poverty, hunger, and dirt” | Describes the monotonous and degrading conditions under which the seamstress works. | Formalism: Repetition emphasizes monotony; Feminist Theory: Highlights the specific burden on working-class women. |

| “Work! work! work! / Till the stars shine through the roof!” | Emphasizes the endless nature of her labor, from dawn until night. | Existentialism: Highlights the lack of agency and autonomy in her life. |

| “It is not linen you’re wearing out, / But human creatures’ lives!” | Critiques the wealthy for ignoring the human cost of their luxuries. | Marxist Theory: Explores class exploitation and alienation. |

| “A Shroud as well as a Shirt” | Suggests her labor not only produces garments but also leads to her own physical deterioration. | Feminist Theory: Shows how the gendered labor of women can result in physical and emotional sacrifice. |

| “Oh, God! that bread should be so dear, / And flesh and blood so cheap!” | Critiques societal priorities that value goods over human lives. | Social Critique: Questions economic systems that devalue human dignity. |

| “From weary chime to chime, / Work—work—work, / As prisoners work for crime!” | Compares her relentless toil to the punishment of criminals, emphasizing its harshness. | Marxist Theory: Labor as punishment reflects industrial alienation and oppression. |

| “O! but to breathe the breath / Of the cowslip and primrose sweet” | Expresses her longing for freedom and connection to nature. | Romanticism: Contrasts industrial life with the idealized freedom of the natural world. |

| “Would that its tone could reach the Rich!” | A direct plea for the wealthy to hear and act on her plight. | New Historicism: Critiques Victorian-era societal inequality and lack of empathy among the elite. |

| “No blessed leisure for Love or hope, / But only time for grief!” | Highlights the emotional toll of her labor, leaving no space for joy or connection. | Feminist Theory: Reveals how economic systems disproportionately deny women emotional and social fulfillment. |

Suggested Readings: “Song of the Shirt” by Thomas Hood

- Eden, Helen Parry. “THOMAS HOOD.” Blackfriars, vol. 7, no. 78, 1926, pp. 554–67. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43810645. Accessed 21 Dec. 2024.

- Edelstein, T. J. “They Sang ‘The Song of the Shirt’: The Visual Iconology of the Seamstress.” Victorian Studies, vol. 23, no. 2, 1980, pp. 183–210. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3827085. Accessed 21 Dec. 2024.

- Gudde, Erwin G., and Edwin G. Gudde. “Traces of English Influences in Freiligrath’s Political and Social Lyrics.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 20, no. 3, 1921, pp. 355–70. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27702589. Accessed 21 Dec. 2024.

- MACLURE, JENNIFER. “Rehearsing Social Justice: Temporal Ghettos and the Poetic Way Out in ‘Goblin Market’ and ‘The Song of the Shirt.'” Victorian Poetry, vol. 53, no. 2, 2015, pp. 151–69. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26160125. Accessed 21 Dec. 2024.

- PITTOCK, MALCOLM. “Gaskell’s Uses of Thomas Hood.” The Gaskell Journal, vol. 25, 2011, pp. 114–18. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45179765. Accessed 21 Dec. 2024.