Introduction: “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

“Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle was published in 2012 in The New Yorker, showcasing the magazine’s penchant for thought-provoking short fiction. Boyle, a renowned author known for his scathing wit and ability to weave social critique into captivating narratives, likely used this platform to explore an unconventional theme through his story.

Main Events in “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

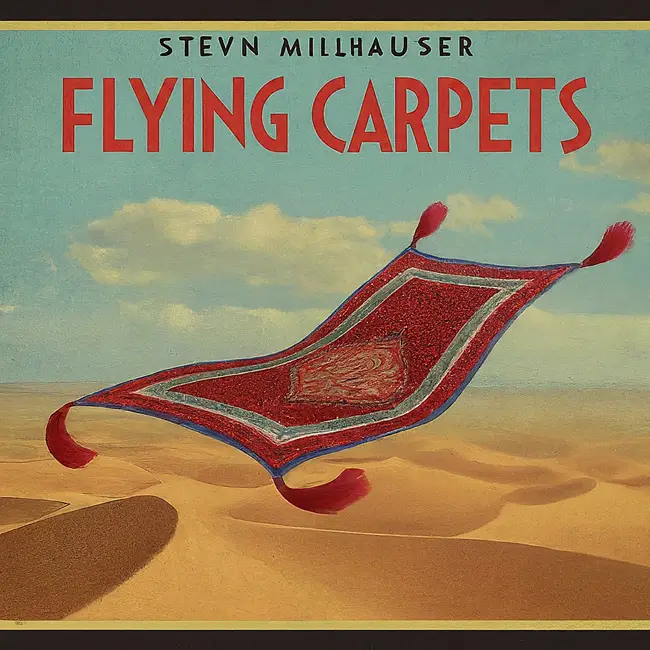

- Flying carpets arrive: The narrator first notices glimpses of flying carpets in other neighborhoods, sparking his curiosity.

- Gift of a flying carpet: The narrator’s father brings home a red and green flying carpet, which is duller than he imagined.

- Initial practice: The narrator cautiously practices flying the carpet in the backyard, following instructions and learning basic maneuvers.

- Night flight: Unable to resist temptation, the narrator takes a solo flight at night after his mother falls asleep.

- Exploration: He soars above his house, enjoying the view of the town and other flying carpets.

- Fear sets in: Venturing too far, the narrator becomes overwhelmed by the vast emptiness of the night sky and fears he won’t return.

- Near miss: He narrowly avoids crashing into rooftops before desperately clinging to the carpet as he descends.

- Safe landing: The narrator lands back in his yard, relieved and shaken by his experience.

- Lingering effects: He develops a fever and spends a few days recovering.

- Loss of interest: The allure of the flying carpet fades after his scary flight.

- Shifting focus: The narrator returns to his usual childhood activities.

- School approaches: With school nearing and other things demanding attention, flying carpets become a forgotten memory.

- Rediscovering the carpet: Cleaning his room, the narrator stumbles upon the rolled-up carpet, now dusty and neglected.

- Banishment to the cellar: He stores the carpet away in the cellar, seemingly putting an end to his flying adventures.

- Winter scene: The story concludes with the narrator playing in the snow, leaving the future of the flying carpets and his relationship with them uncertain.

Literary Devices in “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

| Literary Device | Example | Explanation |

| Allusion | “…a rumor swirling around the schoolyard like a miniature dust devil…” | Refers to a dust devil, a natural phenomenon, to describe a rumor. |

| Characterization | “He himself wasn’t sure if he believed it…” | Reveals the narrator’s uncertainty and cautious nature through his thoughts. |

| Hyperbole | “…a million glittering beetles…” | Uses exaggeration to describe the numerous flying carpets in the night sky. |

| Imagery | “The houses below looked like Monopoly pieces scattered across a green felt board.” | Creates a vivid image by comparing houses to game pieces. |

| Internal Monologue | “Was this all there was to it? A slow, sputtering ascent…” | Reveals the narrator’s internal thoughts and disappointment with the flying carpet. |

| Juxtaposition | “…the carpets, these magical emblems of freedom, were also potential deathtraps.” | Contrasts the freedom of flying carpets with the danger they pose. |

| Metaphor | “The town stretched out below him like a sleeping beast…” | Compares the town to a sleeping beast to evoke a sense of mystery. |

| Metonymy | “…the whine of a distant motor…” | Uses the sound of a motor to represent a car. |

| Onomatopoeia | “…the frantic wheeze of the straining engine…” | Uses sound words (“wheeze”) to create a sense of urgency and struggle. |

| Oxymoron | “…a dull roar…” | Combines opposite terms (“dull” and “roar”) to describe the sound of the flying carpet. |

| Personification | “…the wind clawed at his face…” | Gives human qualities (“clawed”) to a non-human thing (wind) to create a sense of danger. |

| Rhetorical Question | “Where did they all go at night?” | Asks a question not expecting an answer, emphasizing the narrator’s curiosity. |

| Simile | “…the houses thinned like receding hairs…” | Compares the houses shrinking in the distance to receding hairs. |

| Symbolism | The flying carpets can symbolize freedom, exploration, or the allure of the unknown. | An object (flying carpets) represents a larger idea. |

| Understatement | “He wasn’t having much fun.” | Downplays the narrator’s fear and panic during his night flight. |

Characterization in “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

Characterization of The Boy (Narrator) in “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle:

- Curious: The boy is fascinated by the flying carpets and eager to experience them for himself (e.g., following rumors and drawn to their novelty).

- Cautious at First: He initially practices under his mother’s supervision and feels hesitant to fly too high (e.g., following instructions and cautious maneuvers).

- Tempted by Adventure: Despite warnings, he can’t resist the urge to take a solo night flight, showcasing his adventurous spirit (e.g., succumbing to temptation despite potential dangers).

- Naive: He underestimates the potential dangers of the flying carpets, particularly at night (e.g., venturing too far and experiencing fear).

- Prone to Fear: During his nighttime flight, he becomes overwhelmed by the vastness and emptiness, experiencing panic (e.g., near misses and clinging desperately to the carpet).

- Recovers Quickly: He recovers physically from his fever after a few days (e.g., suggesting resilience).

- Loses Interest: Following his scary experience, his fascination with the flying carpet fades (e.g., returning to usual activities and forgetting about them).

- Matures: The experience seems to mark a shift towards a more mature understanding of limitations and potential dangers (e.g., prioritizing familiar activities and leaving the carpet in the cellar).

Major Themes in “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

- Socioeconomic Struggle: One prominent theme in the story is the socioeconomic struggle faced by the protagonists, highlighted through their precarious living conditions and financial instability. The protagonist’s stint as a substitute teacher and Nora’s reluctance to seek employment underscore their limited options and the harsh realities of making ends meet. For instance, the dilapidated shack they initially inhabit, with its leaky roof and lack of amenities, serves as a tangible symbol of their economic hardship.

- Disillusionment and Displacement: Another significant theme is disillusionment and displacement, as the protagonists grapple with shattered dreams and a sense of not belonging. The contrast between their idyllic summer memories and the grim reality of their current situation underscores their disillusionment with life’s promises. Moreover, their visit to Birnam Wood, an opulent enclave that starkly contrasts with their humble existence, accentuates their feelings of displacement and inadequacy in a world of wealth and privilege.

- Relationship Dynamics: The story delves into the complexities of relationships, particularly the strain caused by external pressures and internal conflicts. The protagonist and Nora’s relationship is fraught with tension, exacerbated by their dire circumstances and the challenges they face. Their communication breakdown, evident in moments of bickering and resentment, underscores the erosion of their bond amidst adversity. For instance, their inability to effectively communicate their needs and frustrations leads to further discord in their already strained relationship.

- Search for Stability and Identity: Throughout the narrative, there is a pervasive theme of the search for stability and identity amidst uncertainty. The protagonists’ quest for a new home symbolizes their desire for a sense of security and belonging. Whether it is the dilapidated shack or the grandeur of Birnam Wood, each setting reflects their search for stability in an ever-changing world. Additionally, the protagonist’s internal conflict regarding his role as a provider and his feelings of inadequacy underscore the broader quest for identity in the face of adversity.

Writing Style in “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

- First-Person Point of View: The story unfolds entirely from the narrator’s perspective, placing the reader directly in his headspace. This allows for a sense of immediacy and access to his thoughts, anxieties, and wonder. (e.g., “He himself wasn’t sure if he believed it, but a rumor swirling around the schoolyard like a miniature dust devil…”)

- Vivid Imagery: Boyle uses evocative descriptions to paint a picture of the flying carpets and the boy’s experiences. This imagery helps create a sense of wonder and later, of danger. (e.g., “The houses below looked like Monopoly pieces scattered across a green felt board.”)

- Dark Humor: Boyle injects subtle dark humor throughout the story, which can be unsettling or ironic. This adds complexity and reflects the boy’s potentially naive perspective on the dangers involved. (e.g., “…a dull roar that put him in mind of a malfunctioning furnace…”)

- Conversational Tone: The narrator’s voice feels conversational and informal, as if he’s recounting the events directly to the reader. This creates a sense of intimacy and allows the reader to connect with the boy’s thought process. (e.g., “The next day, after school, he snuck the manual out of the box…”)

- Sparse Dialogue: Dialogue is minimal, further emphasizing the internal world of the narrator and his fascination with the flying carpets.

Literary Theories and Interpretation of “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

| Literary Theory | Interpretation |

| Marxist Criticism | Marxist criticism examines the socioeconomic structures and power dynamics within a text. In “Birnam Wood,” this lens can highlight the disparities between the wealthy inhabitants of Birnam Wood and the struggling protagonists. The story exposes the inequalities inherent in capitalist society, where the working class faces eviction, poverty, and limited opportunities while the wealthy maintain their privilege. Additionally, Marxist analysis can delve into the commodification of labor, as seen in the protagonist’s substitute teaching job and Nora’s reluctance to work, reflecting broader issues of exploitation and alienation. |

| Feminist Criticism | Feminist criticism explores gender dynamics, representation, and the portrayal of women in literature. In “Birnam Wood,” Nora’s character offers fertile ground for feminist analysis. Her agency, or lack thereof, in the narrative, her decision-making process, and her role within the relationship can be scrutinized through this lens. Furthermore, the power dynamics between Nora and the protagonist, as well as societal expectations regarding women’s roles, can be examined. Nora’s actions, desires, and constraints can be analyzed to uncover underlying themes of gender inequality and the impact of patriarchal norms on individual agency. |

| Psychoanalytic Criticism | Psychoanalytic criticism delves into characters’ unconscious desires, motivations, and psychological conflicts. In “Birnam Wood,” the protagonist’s internal struggles and conflicts can be explored through this lens. His frustrations, insecurities, and resentment towards Nora, as well as his feelings of inadequacy as a provider, may stem from deeper psychological issues. Moreover, Nora’s behavior and choices, such as her reluctance to work and her reactions to their predicament, can be analyzed to uncover subconscious drives and anxieties. Psychoanalytic interpretation can provide insight into the characters’ psyches and illuminate the underlying emotional complexities driving their actions. |

| Ecocriticism | Ecocriticism focuses on the relationship between literature and the environment, exploring themes of nature, landscape, and ecology. In “Birnam Wood,” the natural setting plays a significant role, serving as both a backdrop and a mirror to the characters’ inner turmoil. The contrast between the bleakness of the protagonist’s initial dwelling and the lushness of Birnam Wood highlights the interconnectedness between human existence and the natural world. Moreover, the rain, woods, and lake symbolize renewal, transformation, and the cyclical nature of life, mirroring the characters’ journey towards hope and redemption amidst adversity. Ecocritical analysis can uncover the deeper ecological themes embedded within the narrative and their symbolic significance in relation to the human experience. |

Topics, Questions, and Thesis Statements about “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

| Topic | Questions | Thesis Statements |

| Socioeconomic Struggle | 1. How do the protagonists’ socioeconomic circumstances impact their choices and relationships? 2. What role does class disparity play in shaping the narrative and character dynamics? | “Birnam Wood” portrays the impact of socioeconomic struggle on individual agency, relationships, and identity, highlighting the pervasive influence of class disparity on the characters’ lives. |

| Disillusionment and Displacement | 1. How does the contrast between the protagonists’ summer memories and their current reality contribute to themes of disillusionment? 2. In what ways do the settings of the story reflect the characters’ feelings of displacement and inadequacy? | The narrative of “Birnam Wood” explores themes of disillusionment and displacement, revealing the characters’ longing for stability and belonging amidst the upheaval of their lives. |

| Relationship Dynamics | 1. How do external pressures and internal conflicts impact the protagonists’ relationship? 2. What role does communication breakdown play in shaping the dynamics between the protagonists? | Through an analysis of relationship dynamics in “Birnam Wood,” it becomes evident that external pressures and internal conflicts contribute to the erosion of communication and mutual understanding between the protagonists. |

| Search for Stability and Identity | 1. How do the protagonists’ search for a new home symbolize their quest for stability and identity? 2. What internal and external obstacles do the protagonists face in their search for stability and identity? | The narrative of “Birnam Wood” underscores the protagonists’ search for stability and identity amidst uncertainty, reflecting broader themes of resilience, adaptation, and the human desire for security. |

Short Questions/Answers about/on “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

- What is the significance of the title “Birnam Wood”? The title “Birnam Wood” alludes to the forest near Dunsinane in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, where trees are used as camouflage in battle. In Boyle’s story, Birnam Wood represents a contrasting symbol of wealth and privilege, highlighting the disparity between the protagonists’ humble existence and the opulent enclave they encounter.

- How does the rain serve as a metaphor in “Birnam Wood”? The rain in “Birnam Wood” symbolizes the protagonists’ bleak reality and emotional turmoil. It represents decay, hardship, and the erosion of hope as they struggle to navigate their dire circumstances amidst the relentless downpour.

- What role does communication breakdown play in the story? Communication breakdown exacerbates the protagonists’ challenges, leading to misunderstandings and resentment. Their inability to effectively communicate their needs and frustrations contributes to the strain on their relationship and hinders their ability to navigate their predicament together.

- How does the setting reflect the themes of disillusionment and displacement? The contrasting settings of the dilapidated shack and the luxurious Birnam Wood mirror the protagonists’ feelings of disillusionment and displacement. Their memories of idyllic summer days stand in stark contrast to their current reality, highlighting their longing for stability and belonging amidst the upheaval of their lives.

Literary Works Similar to “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

- The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck: Like “Birnam Wood,” Steinbeck’s novel explores themes of socioeconomic struggle, displacement, and the search for stability amidst adversity. Both works depict the challenges faced by individuals and families during times of economic hardship.

- No Country for Old Men by Cormac McCarthy: McCarthy’s novel delves into themes of disillusionment, violence, and moral ambiguity, much like Boyle’s story. Both works feature protagonists navigating a harsh and unforgiving landscape while grappling with internal and external conflicts.

- The Road by Cormac McCarthy: Another work by McCarthy, “The Road,” shares themes of survival, resilience, and the human condition amidst a post-apocalyptic world. Similarly, “Birnam Wood” explores the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

- In Dubious Battle by John Steinbeck: Steinbeck’s novel examines themes of labor strife, social justice, and the human cost of economic inequality. These themes resonate with the socioeconomic struggle depicted in “Birnam Wood,” highlighting the impact of societal forces on individual lives.

- Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates: Yates’ novel delves into themes of suburban disillusionment, societal pressures, and the breakdown of relationships. Similarly, “Birnam Wood” explores the strain on relationships and the disillusionment of the American Dream amidst economic hardship.

Suggested Readings about/on “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

Books:

- Boyle, T. Coraghessan. “Hostages.” The Antioch Review 36.2 (1978): 154-160.

- Boyle, T. Coraghessan. TC Boyle Stories II: The Collected Stories of T. Coraghessan Boyle, Volume II. Vol. 2. Penguin, 2013.

- Boyle, T. Coraghessan. When the killing’s done. A&C Black, 2012.

- Donadieu, Marc Vincent. American picaresque: the early novels of T. Coraghessan Boyle. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2000.

Articles:

- Adams, Elizabeth. “An Interview with T. Coraghessan Boyle.” Chicago Review 37.2/3 (1991): 51-63.

- D’haen, Theo. “The return of history and the minorization of New York: T. Coraghessan Boyle and Richard Russo.” Revue française d’études américaines (1994): 393-403.

- Boyle, T. Coraghessan. “Carnal Knowledge.” Without a Hero and Other Stories (1999): 123-44.

Websites:

- New Yorker (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/09/03/birnam-wood): The New Yorker’s website offers a comprehensive archive of articles, essays, and reviews from its esteemed magazine. This specific link leads to an article titled “Birnam Wood,” published in September 2012. The New Yorker is renowned for its high-quality journalism, fiction, and cultural commentary, making it a trusted source for insightful and thought-provoking content.

- Mookse and the Gripes (https://mookseandgripes.com/reviews/2012/08/27/t-coraghessan-boyle-birnam-wood/): Mookse and the Gripes is a literary website dedicated to reviews, discussions, and analyses of contemporary and classic literature. This particular page provides a review of T. Coraghessan Boyle’s “Birnam Wood,” offering critical insights and interpretations of the story. Mookse and the Gripes is a valuable resource for readers seeking in-depth commentary and thoughtful perspectives on literature.

- T.C. Boyle’s Official Website (https://www.tcboyle.com/): T.C. Boyle’s official website serves as a hub for information about the acclaimed author, featuring news, events, biographical details, and a comprehensive archive of his works. Visitors can explore Boyle’s bibliography, read excerpts from his novels and short stories, and stay updated on upcoming releases and appearances. T.C. Boyle’s website provides fans and readers with a direct connection to the author and his literary world.

Representative Quotations from “Birnam Wood” by T. Coraghessan Boyle

| Quote | Context | Theorization |

| “It rained all that September, a grim, cold, bleached-out rain that found the holes in the roof and painted the corners with a black creeping mold…” | Describes the deteriorating living conditions in the shack where the protagonist and Nora reside after being evicted. The rain symbolizes the bleakness and decay of their situation. | The rain serves as a metaphor for the emotional and financial struggles the couple faces. It represents the gradual erosion of their relationship and their hopes as they confront their dire circumstances. |

| “In the summer, we’d been outside most of the time, reading and lazing in the hammock till it got dark…” | Contrasts the idyllic summer memories with their current grim reality, highlighting the drastic change in their lifestyle and environment. | This quote juxtaposes the carefree days of summer with the harshness of their current situation, emphasizing the loss of innocence and stability. It reflects themes of nostalgia and disillusionment. |

| “I sprang for a cheap TV to keep her company, and then an electric heater the size of a six-pack of beer that nonetheless managed to make the meter spin like a 45.” | Shows the protagonist’s efforts to alleviate their discomfort, despite their financial constraints. | This quote demonstrates the protagonist’s struggle to maintain some semblance of normalcy and comfort in their dire circumstances. It highlights themes of resourcefulness and resilience in the face of adversity. |

| “There were two problems with the house, the first apparent to all three of us, the second only to Nora and me.” | Describes their visit to a potential new rental, revealing both practical and emotional obstacles they face in finding a new home. | This quote illustrates the couple’s shared challenges and individual burdens in their search for stability. It underscores the theme of communication breakdown and the strain it places on their relationship. |

| “‘Ven you vant,’ she said, shrugging, her delicate wheeze of a voice clinging to the hard consonants of her youth, ‘you come.’” | Depicts the dismissive attitude of the landlady towards the couple’s predicament, emphasizing their vulnerability and desperation. | The landlady’s indifference reflects societal attitudes towards those struggling financially. It highlights themes of class disparity and the dehumanizing effects of poverty. |

| “The cold pricked me everywhere, like acupuncture, and I clutched my jeans to my groin, fumbled with a sweatshirt, and hobbled across the room to snatch up the phone.” | Illustrates the physical discomfort and tension in the protagonist’s life, emphasizing the pervasive hardship they endure. | This quote conveys the palpable sense of discomfort and strain in the protagonist’s daily existence. It reinforces the theme of physical and emotional suffering amidst their precarious living conditions. |

| “I didn’t know her. Nora had circled an ad in The Pennysaver, dialled the number, and now here she was, the old lady, waiting for us on the porch…” | Highlights Nora’s initiative in seeking out potential living arrangements, contrasting with the protagonist’s passivity. | Nora’s proactive approach underscores her agency and resilience in the face of adversity. It also reflects gender dynamics and power struggles within the relationship. |

| “‘Forward and backward, not up and down!’” | Shows the tension and frustration between the couple during their journey to Birnam Wood, revealing underlying resentment and communication breakdown. | This quote exemplifies the strain on their relationship and the breakdown of communication under pressure. It underscores the theme of internal conflict and emotional distance between the protagonists. |

| “Then the first house rose up out of the trees on our left, a huge towering thing of stone and glass with a glistening black slate roof and too many gables to count…” | Depicts the stark contrast between their previous living conditions and the opulence of Birnam Wood, emphasizing their sense of displacement and inadequacy. | The juxtaposition of their humble existence with the luxury of Birnam Wood highlights themes of social inequality and the disparity between the haves and have-nots. It also symbolizes their longing for stability and belonging. |

| “I didn’t want to bicker, but I couldn’t help pointing out that we’d passed by the place at least three times already and Nora should have kept her eyes open…” | Reflects the strain on their relationship and the protagonist’s frustration with their situation, highlighting underlying tensions and resentment. | This quote underscores the breakdown of communication and mutual support between the protagonists. It emphasizes the impact of external stressors on their relationship and their ability to navigate challenges together. |