Introduction: “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

“A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson was first published posthumously in 1890, as part of her first series of published poems. The poem exhibits qualities quintessential to Dickinson’s work: playful observation of nature, a focus on the small and seemingly insignificant, and a vibrant use of imagery. Dickinson personifies the raindrops, describing their journey and the transformative effect they have on the natural world. Her characteristic short lines and slant rhyme create a buoyant rhythm that mirrors the joyful energy of the poem itself.

Text: “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

A Drop fell on the Apple Tree –

Another – on the Roof –

A Half a Dozen kissed the Eaves –

And made the Gables laugh –

A few went out to help the Brook

That went to help the Sea –

Myself Conjectured were they Pearls –

What Necklaces could be –

The Dust replaced, in Hoisted Roads –

The Birds jocoser sung –

The Sunshine threw his Hat away –

The Bushes – spangles flung –

The Breezes brought dejected Lutes –

And bathed them in the Glee –

The Orient showed a single Flag,

And signed the fête away –

Annotations: “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

| Stanza | Annotation |

| Stanza 1 (Lines 1–4) | Introduces the central event – a rain shower playfully comes to life. The raindrops are personified with actions like “fell,” “kissed,” and “made the Gables laugh.” This whimsical imagery transforms the ordinary into something delightful and sets the scene with a lighthearted tone. |

| Stanza 2 (Lines 5–8) | The focus widens, emphasizing the interconnectedness of nature. The drops join the brook, flowing towards the sea. The speaker engages in imaginative wonder, contemplating the drops as potential “Pearls,” and envisioning them as “Necklaces.” This highlights the hidden beauty and potential within the natural world. |

| Stanza 3 (Lines 9–12) | Depicts the revitalizing aftermath of the rain. The landscape is renewed: the “Dust” is settled, the birdsong becomes brighter (“jocoser”), the sun emerges from behind the clouds (“threw his Hat away”), and the bushes shimmer with raindrops (“spangles flung”). There’s a sense of joyful transformation. |

| Stanza 4 (Lines 13–16) | The focus shifts from the tangible to the atmospheric. The breezes carry a sound the speaker compares to “dejected Lutes,” but now these instruments are “bathed” in happiness (“Glee”). The final lines use striking imagery of the sunset: “The Orient showed a single Flag” signifies the end of the shower’s celebratory mood. This introduces a subtle note of transience. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

| Device | Explanation | Example from the Poem |

| Anaphora | Repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive lines or clauses. | “A Drop…”, “Another…”, “A few…” |

| Anthropomorphism | Attributing human qualities or actions to something non-human (a type of personification). | “The Dust replaced…”, “The Sunshine threw his Hat away” |

| Dashes | Dickinson’s characteristic punctuation; creates pauses, shifts in tone, and emphasizes specific words. | Throughout the poem, they create a sense of playful spontaneity and conversational tone. |

| Diction | The poet’s specific word choice, contributing to tone and meaning. | Words like “jocoser,” “spangles,” and “Glee” evoke a joyful and celebratory atmosphere. |

| Enjambment | When a sentence or thought continues onto the next line without a pause. | “…The Birds jocoser sung – / The Sunshine threw his Hat away…” |

| Hyperbole | Purposeful exaggeration to create emphasis or humor. | “What Necklaces could be -” (Raindrops are unlikely to form actual necklaces) |

| Imagery | Vivid language appealing to the senses (sight, sound, touch, etc.). | “The Bushes – spangles flung -“, “The Breezes brought dejected Lutes -“ |

| Metaphor | A comparison between two things without using “like” or “as.” | “The Orient showed a single Flag” (The sunset is compared to a flag) |

| Mood | The overall emotional atmosphere of the poem. | The poem evokes a predominantly joyful and playful mood. |

| Onomatopoeia | Words that imitate the sounds they describe. | While not overly present, words like “kissed” subtly suggest the sound of raindrops. |

| Oxymoron | Combines seemingly contradictory terms to create a surprising or thought-provoking effect. | “dejected Lutes” (Musical instruments aren’t typically dejected) |

| Personification | Gives human qualities or actions to non-human things. | Numerous examples: raindrops “kiss,” dust is “replaced,” birds sing more “jocoser,” etc. |

| Punctuation | Dickinson’s extensive use of dashes and limited use of other punctuation creates rhythm and emphasis. | The dashes throughout the poem give a sense of conversational informality. |

| Repetition | Repeating words or phrases for emphasis and structure. | “A Drop…”, “Another…”, “The…” |

| Rhyme (Slant/Near Rhyme) | Words with similar, but not identical, end sounds. | “Tree” and “Roof,” “Sea” and “Glee” |

| Rhythm | The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables creating a sense of musicality. | The poem’s short lines and varying rhyme contribute to a playful rhythm. |

| Simile | Comparison between two things using “like” or “as”. | While not the primary device, the poem includes an implied simile in “dejected Lutes.” |

| Symbolism | Using images or objects to represent broader ideas or concepts. | Raindrops symbolize renewal; the sunset suggests the fleeting nature of joy. |

| Tone | The poet’s attitude towards the subject matter. | The poem’s tone is predominantly playful, whimsical, and celebratory. |

Themes: “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

- The Joyful Transformation of Nature: The poem traces the path of raindrops, showing their positive impact on the environment. Dust is settled, birds sing brightly, and the sun reemerges (“The Sunshine threw his Hat away”). These vivid details illustrate nature’s ability to revitalize itself, creating a sense of joyful renewal.

- Finding Wonder in the Ordinary: Dickinson elevates a simple rainstorm into an event laden with beauty and significance. She imagines raindrops transforming into “Pearls” and envisions “Necklaces.” This imaginative leap suggests that wonder can be found in the most commonplace occurrences if we look for it.

- Interconnectedness of Nature: The poem highlights the cyclical flow of the natural world. Raindrops nourish the apple tree, join a brook, and eventually reach the vast sea. This emphasizes the interconnectedness of all things within the ecosystem and celebrates nature’s grand design.

- The Fleeting Nature of Joy: The poem’s final stanza introduces a subtle shift. The sunset, depicted as a flag being lowered, symbolizes the end of the celebratory atmosphere brought by the rain. This underscores the transience of both joy and natural phenomena, reminding us of their preciousness.

Literary Theories and “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

| Literary Theory | Explanation | Application to “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” |

| Formalism / New Criticism | Focused on analyzing the text itself – its form, structure, literary devices, and how they create meaning. | Analyzing the effects of Dickinson’s characteristic dashes, her playful use of personification, the poem’s rhyme scheme, and its overall lighthearted tone. |

| Ecocriticism | Examines the relationship between literature and the natural environment. | Exploring how the poem depicts the transformative power of rain, celebrates the interconnectedness of nature, and emphasizes the importance of observing the natural world. |

| Feminist Criticism | Focuses on gender roles, power dynamics, and female representation within literature. | Analyzing the poem’s potentially subversive act of finding wonder and power in a traditionally “feminine” subject like nature. It can also explore how the poem challenges or reinforces traditional gender roles. |

| Reader-Response Theory | Emphasizes the reader’s role in creating meaning from the text. Each reader brings their unique experiences, which influence their interpretation. | The poem’s simple language and playful imagery can be interpreted on multiple levels. A child might find delight in the personified raindrops, while an adult might focus on themes of renewal and transience. |

Critical Questions about “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

- How does Dickinson’s use of personification shape the poem’s portrayal of nature?

- Answer: By assigning human traits to raindrops, dust, birds, and even the sunshine, Dickinson transforms nature into a playful and dynamic force. This blurs the line between inanimate and animate, suggesting a world teeming with life and energy that exists beyond mere physical descriptions.

- What is the significance of the rain’s journey, from the apple tree to the seaAnswer: This journey highlights the interconnectedness of nature, emphasizing how seemingly small elements contribute to a larger, cyclical system. It might also symbolize life’s journey and its transformative power, suggesting that even the most insignificant occurrences have a role to play.

- How does the poem’s structure (short lines, dashes, slant rhyme) contribute to its overall meaning and tone?

- Answer: The poem’s structure mirrors the playful, spontaneous nature of a rain shower. The short lines and dashes create a sense of lightness, while the slant rhyme adds an element of surprise and delight, further contributing to the poem’s whimsical tone.

- How does the poem’s ending shift the overall mood, and what implications does this have for its thematic depth?

- Answer: The image of the sunset (“The Orient showed a single Flag”) introduces a subtle note of melancholy. This hints at the fleeting nature of joy and the ever-changing rhythms of the natural world, adding a layer of complexity to the poem’s initially celebratory tone.

Literary Works Similar to “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

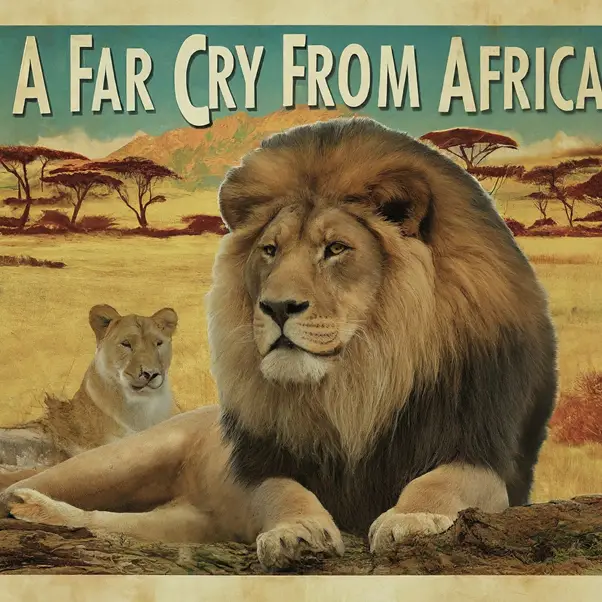

- Other poems by Emily Dickinson: Dickinson frequently explored themes of nature, the power of observation, and finding joy in the ordinary. Poems like “I taste a liquor never brewed” or “There’s a certain Slant of light” share similar qualities to “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree.”

- Nature Poetry by the Romantics: Works by poets like William Wordsworth (“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”) or John Keats (“Ode to a Nightingale”) often celebrate the beauty and transformative power of the natural world, aligning thematically with Dickinson’s poem.

- William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence and Experience”: Blake’s collection includes poems with a childlike sense of wonder and often use natural imagery in symbolic ways. This echoes the tone and perspective in “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree.”

- Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Poetry: Hopkins, like Dickinson, was a stylistic innovator. His poems, such as “Pied Beauty” or “God’s Grandeur,” showcase a deep appreciation of nature and its intricate detail, mirroring Dickinson’s close observation.

- Modernist Poetry with Natural Themes: Works by poets like Robert Frost (“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening“) or Wallace Stevens (“Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”) explore the relationship between humans and the natural world, often in nuanced, complex ways that invite multiple interpretations.

Key Similarities:

- Focus on Nature: These works often center on the natural world, finding beauty and meaning in both the grand and the seemingly quotidian.

- Whimsy and Imagination: Some of these works share a sense of playfulness and imaginative wonder similar to Dickinson’s perspective.

- Symbolism: They commonly use natural imagery symbolically, hinting at deeper philosophical or spiritual meanings.

Suggested Readings: “A Drop Fell on the Apple Tree” by Emily Dickinson

Books:

- Bennett, Paula. Emily Dickinson: Woman Poet. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1990. (Provides critical analysis of Dickinson’s poetry and considers her work within its social and historical context )

- Crumbley, Paul. Inflections of the Pen: Dash and Voice in Emily Dickinson. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1997. (Offers an in-depth examination of how Dickinson uses dashes and other punctuation to create meaning.)

- Farr, Judith, ed. Emily Dickinson: A Collection of Critical Essays. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996. (A compilation of critical essays representing varied perspectives on Dickinson’s work.)

Articles:

- Diehl, Joanne Feit. “Come Slowly – Eden: An Exploration of Emily Dickinson’s Aesthetics.” Harvard Library Bulletin, vol. 23, no. 4, 1975, pp. 373–386. JSTOR. (Analyzes Dickinson’s use of language and imagery to evoke sensory experiences.)

Websites:

- Emily Dickinson Museum: https://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org/ (Offers biographical information, access to Dickinson’s manuscripts, and curated resources for analysis.)

- The Emily Dickinson Archive: https://www.edickinson.org/ (A comprehensive digital archive with high-quality images of Dickinson’s manuscripts and scholarly resources for analysis.)