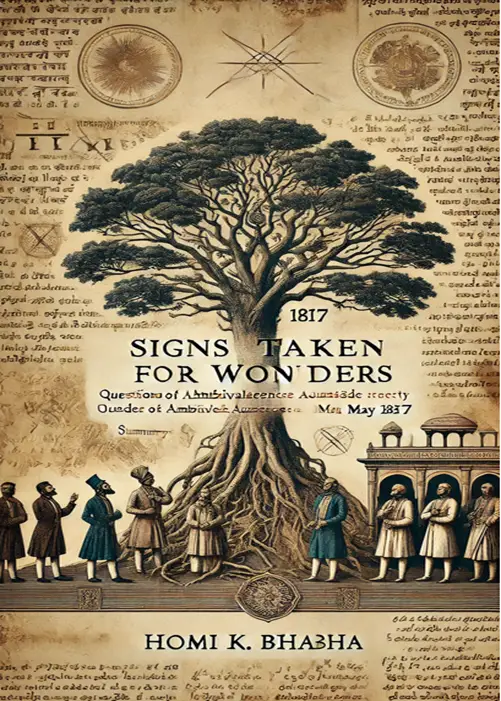

Introduction: “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha

“Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha was first published in 1992 in the Critical Inquiry journal. This essay is a seminal work in postcolonial studies and literary theory. It explores the complex interplay between colonialism, nationalism, and cultural identity through the lens of a historical event: the meeting between the British colonial official William Fry and the Indian nationalist leader Raja Ram Mohan Roy under a banyan tree outside Delhi in 1817. Bhabha’s analysis of this encounter highlights the ambivalence and tensions inherent in colonial power relations and the ways in which cultural identities are constructed and contested. The essay’s significance lies in its contribution to understanding the dynamics of colonialism and postcolonialism, and its impact on shaping the field of literary theory.

Summary of “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha

- Colonial Authority and the English Book: Bhabha begins by examining the role of the English book in colonial settings, particularly its symbolic significance as an emblem of colonial authority and cultural dominance. The discovery of the book in colonial territories, such as the Gospel translated into the Hindoostanee language, becomes a moment of both epiphany and imposition. The English book, described as “signs taken for wonders,” serves as an insignia of colonial power, asserting the colonizer’s control over the native population through language and religion (Bhabha, p. 145). This authority is reinforced by the repeated, translated, and often misread presence of the book, which paradoxically displaces its own origin and creates a wondrous yet alienating presence among the colonized. The narrative of Anund Messeh, an Indian catechist who discovers a group of natives with the translated Gospel, exemplifies how the book’s authority is both recognized and contested by the indigenous people (Bhabha, pp. 144-145).

- Ambivalence in Colonial Encounters: Bhabha highlights the ambivalence inherent in the colonial encounter, where the English book, while representing a source of power, also becomes a site of translation, misinterpretation, and resistance by the colonized. This ambivalence is evident in the natives’ belief that the book was a divine gift, received from an angel, rather than a product of European missionaries (Bhabha, p. 146). The conversation between Anund Messeh and the natives under the tree near Delhi reveals a complex dynamic where the colonized both accept and resist the authority of the English book. The book’s miraculous appearance is both a sign of its power and an indication of its displacement from its original context. Bhabha argues that this scenario exemplifies how colonial authority is established through a process of repetition and translation, which simultaneously asserts and undermines its power (Bhabha, p. 148).

- Cultural Mimicry and Hybridity: In his discussion of mimicry and hybridity, Bhabha introduces these concepts as forms of colonial resistance and survival. Mimicry, in particular, is described as a form of imitation that distorts and displaces the colonizer’s authority, creating a space of ambivalence and uncertainty. The natives’ adoption of the English book, while simultaneously misinterpreting its content and significance, represents a form of mimicry that challenges the colonizer’s claims to cultural superiority (Bhabha, p. 150). This mimicry leads to the creation of hybrid identities that resist the binary oppositions of colonizer and colonized. Bhabha notes that this hybridity is not simply a mixture of cultures but a strategic reversal of colonial domination, where the colonized use the tools of the colonizer to subvert their authority (Bhabha, p. 155). The hybrid identity, therefore, becomes a site of both compliance and resistance, revealing the instability and ambivalence of colonial power.

- Impact of Colonial Discourse: Bhabha’s essay also explores the impact of colonial discourse on the identity of the colonized. He argues that colonial discourse creates a split identity, where the colonized are portrayed as both subjects to be civilized and as inherently different from the colonizer. This split is evident in the stereotypes and representations of the colonized, such as the “simian Negro” and the “effeminate Asiatic male,” which serve to both fix and destabilize colonial identities (Bhabha, p. 153). These representations are not merely reflections of colonial attitudes but are active components of the colonial power structure, which seeks to define and control the identity of the colonized. Bhabha’s analysis reveals how these stereotypes function as tools of colonial authority, creating an ambivalent space where the colonized are both recognized and marginalized within the colonial system (Bhabha, p. 154).

- Resistance through Cultural Difference: Bhabha emphasizes the role of cultural difference as a form of resistance against colonial authority. The natives’ refusal to accept the sacrament, despite their willingness to be baptized, illustrates how cultural practices can serve as a means of resisting colonial imposition (Bhabha, p. 147). The insistence on maintaining dietary laws, for example, challenges the universality of the Christian doctrine as presented by the colonizers. Bhabha argues that this resistance is not simply a rejection of colonial power but a strategic use of cultural difference to assert autonomy and challenge the authority of the colonizer (Bhabha, p. 160). This resistance is further complicated by the fact that the colonized often adopt elements of the colonizer’s culture, creating a hybrid identity that is both a site of resistance and a means of survival within the colonial system.

- Authority and the Reality Effect: Bhabha discusses how colonial authority is maintained through the creation of what he calls a “reality effect,” where the presence of the English book and its associated power is made to appear natural and unquestionable (Bhabha, p. 152). This reality effect is achieved through the strategic use of visibility and recognition, where the book’s authority is reinforced by its repeated appearance in colonial discourse. However, Bhabha argues that this authority is constantly under threat from the very differences it seeks to erase. The colonial text, in its attempt to establish a singular narrative of power, inadvertently reveals its own ambivalence and instability (Bhabha, p. 153). The natives’ questioning of the book’s origin and authority, for instance, disrupts the reality effect and exposes the gaps and contradictions within the colonial narrative (Bhabha, pp. 159-160).

- Hybridity as a Challenge to Authority: Hybridity is a central theme in Bhabha’s essay, representing a challenge to the clear boundaries of colonial power and identity. Bhabha argues that the hybrid identity, formed through the interaction of colonizer and colonized, destabilizes the binary oppositions that underpin colonial authority (Bhabha, p. 156). The hybrid identity is not simply a mixture of two cultures but a site of conflict and negotiation, where the colonized use the tools of the colonizer to resist and subvert their authority. This hybridity is evident in the natives’ adoption of the English book, which they reinterpret and repurpose according to their own cultural context (Bhabha, p. 161). The hybrid identity thus becomes a space where colonial authority is both asserted and undermined, revealing the ambivalence and complexity of the colonial encounter (Bhabha, pp. 162-163).

- Disavowal and Colonial Power: Bhabha examines the concept of disavowal in the context of colonial power, where the colonizer maintains authority by denying the cultural differences and historical realities of the colonized (Bhabha, p. 160). This disavowal is evident in the way Anund Messeh dismisses the natives’ cultural practices and insists on the universality of the Christian doctrine. However, this disavowal creates a paradox where the colonizer’s authority is both asserted and undermined by its reliance on the very differences it seeks to erase. Bhabha argues that this paradox is at the heart of colonial power, where the authority of the colonizer is always precarious and subject to challenge from the colonized (Bhabha, p. 162). The natives’ questioning of the English book and their refusal to fully accept its authority illustrate how the disavowal of cultural difference can lead to resistance and the eventual destabilization of colonial power (Bhabha, p. 160).

- Conclusion on Colonial Authority: In conclusion, Bhabha emphasizes the ambivalence and instability of colonial authority, where the symbols of power, such as the English book, are constantly contested and reinterpreted by the colonized. This contestation is not merely a rejection of colonial power but a complex negotiation where the colonized use the tools of the colonizer to assert their own identity and challenge the authority of the colonizer (Bhabha, p. 163). The essay illustrates how colonial authority, far from being a monolithic force, is fraught with contradictions and tensions that reveal the limits of colonial power. Bhabha’s analysis of the hybrid identity and the ambivalence of colonial discourse provides a nuanced understanding of the colonial encounter, where power is both asserted and contested in a dynamic and unstable process (Bhabha, p. 164).

Literary Terms/Concepts in “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha

| Term/Concept | Explanation |

| Colonial Mimicry | A strategy employed by colonized subjects to imitate the colonizer’s culture and norms, often as a form of resistance or adaptation. |

| Ambivalence | A state of having mixed feelings or contradictory attitudes towards something. In Bhabha’s essay, it refers to the complex relationship between colonizer and colonized, characterized by both attraction and repulsion. |

| Authority | The power to give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience. In the essay, it’s related to the colonial power structure and the English language as a tool of control. |

| Discourse | A system of language that shapes how we think and perceive the world. Bhabha analyzes the discourse of colonialism to understand how it constructs power relations, cultural identities, and the colonial subject. |

| Entstellung | A German term meaning “displacement” or “distortion.” Bhabha uses it to describe the way colonial power disrupts, transforms, and repositions cultural practices. |

| Hybridity | The mixing of different cultural elements to create something new. Bhabha argues that hybridity is a common feature of colonial encounters, but it’s not always a harmonious process. |

| Othering | The process of defining oneself or one’s group in opposition to another group. In colonialism, the colonizer often “others” the colonized, creating a hierarchical relationship. |

| Orientalism | A Western way of representing and understanding the East, often based on stereotypes and generalizations. Bhabha critiques Orientalism as a form of colonial discourse that reinforces Western dominance. |

| Subaltern | A term used to describe marginalized groups who are excluded from dominant power structures. Bhabha’s essay focuses on the subaltern experience of the colonized, who often struggle to articulate their voices and perspectives. |

| Transparency | The appearance of being clear, honest, and open. Bhabha argues that the transparency of colonial authority is often illusory, as it masks underlying power dynamics and discriminatory practices. |

| Disavowal | The act of denying or refusing to acknowledge something. In colonialism, disavowal is a strategy used by colonizers to maintain their sense of superiority and avoid confronting the contradictions of their power. |

| Agency | The capacity of individuals or groups to act independently and make choices. Bhabha’s essay explores the limited agency of colonized subjects, who often find their choices constrained by colonial power structures. |

| Postcolonial Studies | A field of academic study that examines the legacy of colonialism and its impact on societies, cultures, and identities. Bhabha’s essay is a significant contribution to postcolonial studies. |

| Cultural Studies | A broad field of inquiry that examines culture in all its forms, including literature, art, media, and social practices. Bhabha’s essay draws from cultural studies to analyze the cultural implications of colonialism. |

| Interpellation | A concept from Marxist theory that refers to the way individuals are hailed or addressed by ideological structures. In colonialism, colonized subjects are often interpellated in ways that reinforce their subordinate status. |

Contribution of “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha to Literary Theory/Theories

- Subaltern Studies: Bhabha’s essay contributes to the subaltern studies movement by focusing on the voices and experiences of marginalized groups within colonial contexts.

- Hybridity: He introduces the concept of hybridity to challenge the notion of pure cultural identities and to highlight the complex interactions between colonizer and colonized.

- Ambivalence and Mimicry: Bhabha’s analysis of ambivalence and mimicry provides insights into the strategies employed by colonized subjects to navigate colonial power structures.

2. Cultural Studies:

- Cultural Representation: Bhabha’s essay examines the ways in which culture is represented and constructed within colonial discourses.

- Power and Knowledge: He explores the relationship between power and knowledge, arguing that knowledge is often used to justify and maintain colonial domination.

- Deconstruction: Bhabha draws on deconstruction to analyze the underlying structures and assumptions of colonial discourse.

- Differance: He uses Derrida’s concept of différance to highlight the instability and undecidability of language and meaning in colonial contexts.

4. Psychoanalysis:

- Unconscious: Bhabha uses psychoanalytic concepts to explore the unconscious desires and anxieties that shape colonial power relations.

- Fantasy: He analyzes the role of fantasy in constructing colonial identities and maintaining colonial power.

Specific references to theories can be found throughout the essay, but some key examples include:

- Postcolonial Theory: The discussion of subaltern agency, hybridity, and mimicry (p. 148).

- Cultural Studies: The analysis of the cultural representation of the “English book” (p. 144).

- Poststructuralism: The use of deconstruction to examine the ambivalence of colonial authority (p. 150).

- Psychoanalysis: The exploration of the unconscious desires and anxieties underlying colonial power (p. 152).

Examples of Critiques Through “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha

| Literary Work | Critique through Bhabha’s Lens | Key Concepts from Bhabha |

| Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad | Bhabha’s concept of ambivalence can be applied to Conrad’s portrayal of colonial authority, where Marlow’s encounter with Towson’s manual symbolizes the colonial imposition of English knowledge and its simultaneous dislocation and displacement in the African context. The colonial text, while asserting power, reveals its own instability and contradictions through the characters’ interactions with colonial symbols like the book. | Ambivalence, Colonial Authority, Displacement, Reality Effect |

| A Passage to India by E.M. Forster | Through Bhabha’s framework, Forster’s depiction of the English in India can be seen as a narrative of colonial authority that is both asserted and undermined. The interactions between the English and Indian characters exemplify the ambivalence of colonial power, where the English book or law, intended to establish order, instead exposes the underlying cultural differences and the limitations of colonial control. | Hybridity, Ambivalence, Colonial Difference, Mimicry |

| The Mimic Men by V.S. Naipaul | Naipaul’s novel can be critiqued using Bhabha’s idea of mimicry, where the protagonist, Ralph Singh, embodies the colonial subject who imitates the colonizer’s ways but ultimately reveals the inadequacies and contradictions of colonial authority. Singh’s hybrid identity, caught between his colonial upbringing and postcolonial reality, reflects Bhabha’s concept of the ambivalence and instability inherent in colonial and postcolonial identities. | Mimicry, Hybridity, Colonial Identity, Ambivalence |

| Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë | Applying Bhabha’s theory to Jane Eyre, the portrayal of Bertha Mason, the Creole “madwoman,” can be seen as a manifestation of colonial difference and ambivalence. Bertha’s presence in the novel represents the disavowed colonial “other,” whose existence disrupts the narrative of English civility and authority. Through Bhabha’s lens, Bertha’s character challenges the imperialist assumptions underlying the English literary canon. | Colonial Difference, Disavowal, Ambivalence, Hybrid Identity |

Criticism Against “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha

- Overemphasis on Ambivalence: Some critics argue that Bhabha’s focus on ambivalence can obscure the more oppressive aspects of colonial power. They suggest that his analysis might downplay the experiences of those who suffered directly under colonial rule.

- Essentialism: Bhabha has been criticized for essentializing certain concepts, such as “culture” and “identity.” Some argue that his approach can lead to a simplified understanding of complex cultural dynamics.

- Eurocentrism: Some critics contend that Bhabha’s analysis, while valuable, is still influenced by a Eurocentric perspective. They argue that his focus on the “English book” as a central symbol of colonial authority may overlook the agency and resistance of colonized subjects.

- Lack of Historical Specificity: While Bhabha’s essay is insightful, some critics argue that it could benefit from more specific historical context. They suggest that a deeper understanding of the historical context would allow for a more nuanced analysis of the events and relationships described.

- Overreliance on Theory: While Bhabha’s use of theoretical concepts is valuable, some critics argue that his analysis can become overly theoretical and detached from the lived experiences of people in colonial contexts.

Suggested Readings: “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha

- Bhabha, Homi K. “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 1, 1985, pp. 144-165. The University of Chicago Press. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/448325

- Young, Robert J. C. Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture, and Race. Routledge, 1995. https://www.routledge.com/Colonial-Desire-Hybridity-in-Theory-Culture-and-Race/Young/p/book/9780415053746

- Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2006. https://www.routledge.com/The-Post-Colonial-Studies-Reader-2nd-Edition/Ashcroft-Griffiths-Tiffin/p/book/9780415345650

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, University of Illinois Press, 1988, pp. 271-313. https://www.sfu.ca/iirp/documents/spivak.pdf

- Boehmer, Elleke. Colonial and Postcolonial Literature: Migrant Metaphors. 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2005. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/colonial-and-postcolonial-literature-9780199253715?cc=us&lang=en&

- Loomba, Ania. Colonialism/Postcolonialism. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2005. https://www.routledge.com/ColonialismPostcolonialism-2nd-Edition/Loomba/p/book/9780415350647

- Gandhi, Leela. Postcolonial Theory: A Critical Introduction. Columbia University Press, 1998. https://cup.columbia.edu/book/postcolonial-theory/9780231112800

- Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. Vintage Books, 1993. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/160518/culture-and-imperialism-by-edward-w-said/

- Hall, Stuart. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, edited by Jonathan Rutherford, Lawrence & Wishart, 1990, pp. 222-237. https://www.blackwellpublishing.com/content/BPL_Images/Content_store/Sample_chapter/0631225130/Hall.pdf

- Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2002. https://www.routledge.com/The-Empire-Writes-Back-Theory-and-Practice-in-Post-Colonial-Literatures/Ashcroft-Griffiths-Tiffin/p/book/9780415280203

Representative Quotations from “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817” by Homi K. Bhabha with Explanation

| Quotation | Explanation |

| “The discovery of the book is, at once, a moment of originality and authority, as well as a process of displacement that, paradoxically, makes the presence of the book wondrous to the extent to which it is repeated, translated, misread, displaced.” | Bhabha discusses how the English book, as a symbol of colonial authority, simultaneously asserts dominance and undergoes a process of translation and misinterpretation by the colonized, creating an ambivalent presence. |

| “It is with the emblem of the English book—’signs taken for wonders’—as an insignia of colonial authority and a signifier of colonial desire and discipline, that I want to begin this essay.” | Bhabha introduces the central theme of the essay, where the English book represents both the power of the colonizers and the complex relationship between authority and the colonized subjects’ interpretations. |

| “The colonial presence is always ambivalent, split between its appearance as original and authoritative and its articulation as repetition and difference.” | This quote highlights Bhabha’s concept of ambivalence in colonial discourse, where the colonizers’ authority is both affirmed and challenged by the repetition and adaptation of their symbols by the colonized. |

| “Hybridity is the revaluation of the assumption of colonial identity through the repetition of discriminatory identity effects.” | Bhabha describes hybridity as a process where colonial identities are reshaped through the repetition of stereotypes, leading to the emergence of new, complex identities that resist simple categorization. |

| “Mimicry is, thus, the sign of a double articulation; a complex strategy of reform, regulation, and discipline, which ‘appropriates’ the Other as it visualizes power.” | Here, Bhabha explains mimicry as a colonial strategy that both asserts power and creates a space for resistance, as the colonized subjects imitate the colonizers in a way that subtly undermines their authority. |

| “The exercise of colonialist authority, however, requires the production of differentiations, individuations, identity effects through which discriminatory practices can map out subject populations.” | Bhabha argues that colonial authority relies on creating distinctions and identities among the colonized to maintain control, highlighting how power operates through the construction of differences. |

| “The discovery of the English book installs the sign of appropriate representation: the word of God, truth, art creates the conditions for a beginning, a practice of history and narrative.” | This quote emphasizes how the English book, as a symbol of colonial authority, becomes a foundational text that shapes historical and narrative practices within the colonial context. |

| “To be authoritative, its rules of recognition must reflect consensual knowledge or opinion; to be powerful, these rules of recognition must be breached in order to represent the exorbitant objects of discrimination that lie beyond its purview.” | Bhabha discusses the paradox of colonial authority, which must be both recognized as legitimate and yet continually challenged by the very differences it seeks to control, creating an unstable power dynamic. |

| “The native questions quite literally turn the origin of the book into an enigma. First: How can the word of God come from the flesh-eating mouths of the English?” | This quote illustrates the resistance of the colonized to colonial authority, as they question the legitimacy of the English book and its origins, challenging the assumed universality of colonial power. |

| “The hybrid object, however, retains the actual semblance of the authoritative symbol but revalues its presence by resiting it as the signifier of Entstellung—after the intervention of difference.” | Bhabha describes hybridity as a process where colonial symbols are reinterpreted and transformed by the colonized, resulting in a new meaning that reflects the intervention of cultural difference. |