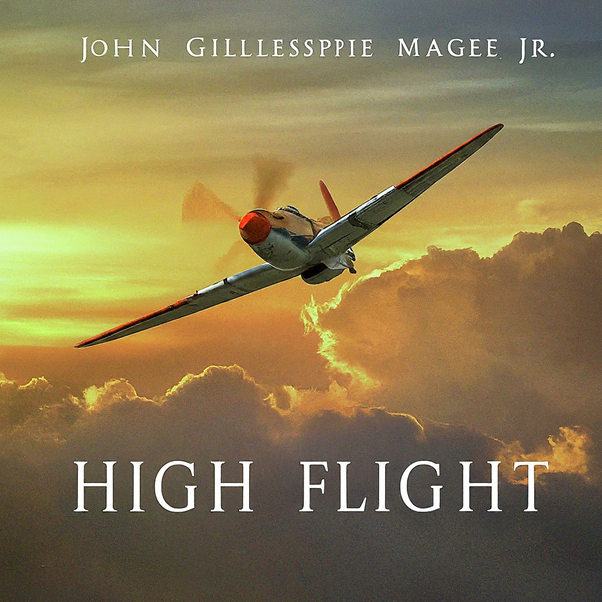

Introduction: “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

“High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr. was published posthumously after his death in 1941, though it is unclear if it was included in a formal collection of his work. This iconic sonnet vividly portrays the exhilaration and transcendent spirituality of flight from a pilot’s perspective. Themes of freedom, adventure, and the boundless nature of the sky permeate the poem. Its unique quality lies in Magee’s ability to translate the raw physical sensation of flight into a moving metaphor for the human spirit’s capacity to soar beyond earthly limitations.

Text: “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds,—and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air ….

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark nor ever eagle flew—

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

Annotations: “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

| Line | Annotation |

| Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth | The exclamation “Oh!” expresses the pilot’s intense joy and liberation upon breaking free of Earth’s hold. |

| And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings; | Evocative imagery: The sky becomes a dance floor and the plane’s wings gleam with joyful reflection. |

| Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth | The climb is joyful and effortless; the poet shares in the playful, swirling movement of the clouds. |

| of sun-split clouds,—and done a hundred things | Emphasizes the pilot’s freedom to perform exhilarating maneuvers unimaginable to those bound to the ground. |

| You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung | The speaker directly addresses those on Earth, contrasting their limited perspective with his boundless flight. |

| High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there, | Emphasizes the quiet wonder of high-altitude flight and the sense of suspension in the vastness of the sky. |

| I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung | Vivid portrayal of speed and interaction with the elements; “shouting” suggests the wind’s force. |

| My eager craft through footless halls of air …. | The air becomes a grand structure, open for the pilot to explore without the constraints of earthly paths. |

| Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue | Repeated “up” emphasizes ascent; “delirious, burning” implies ecstatic, otherworldly sensations. |

| I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace | Despite the forces of nature, ascent feels effortless; “grace” suggests a sense of spiritual elevation. |

| Where never lark nor even eagle flew— | Pilot enters a realm untouched by natural creatures, a space previously thought reserved for the divine. |

| And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod | “Silent… mind” shows reverence; “trod” implies walking, a human act in an inhuman place. |

| The high untrespassed sanctity of space, | Space is sacred, previously unviolated. The pilot’s presence feels almost transgressive. |

| Put out my hand, and touched the face of God. | The ultimate culmination of the flight; a profound, metaphorical experience signifying a closeness to God. |

Literary And Poetic Devices: “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

| # | Literary/Poetic Device | Definition | Example from “High Flight” |

| 1 | Metaphor | A direct comparison between two unlike things | “…danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings” (wings compared to laughter) |

| 2 | Personification | Giving human-like qualities to non-human things | “…the shouting wind…” (wind given the ability to shout) |

| 3 | Imagery | Vivid language appealing to the senses | “Sun-split clouds,” “footless halls of air” |

| 4 | Alliteration | Repetition of consonant sounds at the start of words | “…sunlit silence. Hov’ring…” (repetition of the “s” and “h” sounds) |

| 5 | Assonance | Repetition of vowel sounds within words | “…long, delirious, burning blue…” (repetition of the “uh” sound) |

| 6 | Enjambment | Continuation of a sentence across lines without punctuation | “…joined the tumbling mirth / of sun-split clouds…” |

| 7 | Symbolism | Use of objects to represent abstract ideas | The plane and flight represent freedom, transcendence, spiritual ascent |

| 8 | Hyperbole | Exaggeration for emphasis | “…done a hundred things You have not dreamed of…” |

| 9 | Anaphora | Repetition of a word or phrase at the start of lines | “Up, up the long…” |

| 10 | Diction | Choice of words, influencing the poem’s tone | Words like “mirth,” “delirious,” and “trod” create a joyful, reverent tone |

| 11 | Inversion | Reversal of typical word order for emphasis | “Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.” (Normal: “I put out…”) |

| 12 | Simile | A comparison using “like” or “as” | Not strongly present in this poem |

| 13 | Juxtaposition | Placement of contrasting ideas near each other | “…sunlit silence…” (contrasting sensations of sunlight and silence) |

| 14 | Onomatopoeia | Words whose sound imitates their meaning | Not strongly present in this poem |

| 15 | Tone | The speaker’s attitude towards the subject | Awe, exhilaration, wonder, reverence |

Themes: “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

1. Freedom and Exhilaration

- The boundless nature of flight: The poem continuously emphasizes the lack of restrictions in the sky. Lines like “slipped the surly bonds of Earth,” “footless halls of air,” and “done a hundred things you have not dreamed of” all point to the liberating feeling of flight.

- Joy and playful energy: The imagery evokes a sense of delight: “laughter-silvered wings,” “tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds,” and the “delirious, burning blue.” The speaker revels in a childlike sense of freedom to explore and play.

2. Transcendence and the Limitless

- Pushing physical boundaries: The speaker doesn’t just fly, but ascends further and further upward – “sunward I’ve climbed,” “topped the wind-swept heights.” This reflects a human desire to break past perceived limitations.

- Entering the untouchable: The flight carries the pilot beyond the realm of nature (“Where never lark nor even eagle flew”) and into a traditionally spiritual space (“The high untrespassed sanctity of space”). This suggests a transcendence of the earthly and a reaching for the boundless.

3. Spirituality and Connection to the Divine

- Sacredness of space: The phrase “untrespassed sanctity of space” implies this higher realm was previously untouched and belongs to the divine. The pilot entering this space hints at a human desire for communion with the sacred.

- The climactic encounter: The final line, “Put out my hand and touched the face of God,” is the culmination of the flight. Whether interpreted literally or metaphorically, it portrays an intimate, spiritual experience made possible by this transcendent journey.

4. The Pilot’s Unique Perspective

- Contrast with those below: The speaker addresses “you” on the ground, highlighting their limited understanding compared to his experience (“wheeled and soared and swung…You have not dreamed of”). This reinforces the transformative power of his perspective gained through flight.

- Silent, solitary contemplation: The “sunlit silence” and the pilot’s mind that is “silent” yet “lifting” underscores a shift away from the noise and distractions of the earthly world. The poem implies quiet reflection is part of this elevated experience.

Literary Theories and “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

| Literary Theory | How It Applies to “High Flight” | References from the Poem |

| Formalism / New Criticism | Focuses on the text itself, analyzing form, structure, and literary devices to derive meaning. | * Metaphors (“laughter-silvered wings”) and personification (“shouting wind”) create vivid imagery. * Enjambment and repetition (“Up, up…”) contribute to the sense of ascent and freedom. * Analysis of the poem’s sonnet form and its traditional structure. |

| Reader-Response Theory | Emphasizes the reader’s active role in creating meaning. Individual experiences will shape interpretations of the poem. | * Some readers may focus on the exhilaration of flight, while others may focus on the spiritual themes. * Prior knowledge of aviation or military history would influence a reader’s understanding. * A reader’s personal beliefs about the divine would shape their interpretation of the final line. |

| Biographical Criticism | Examines how an author’s life and experiences shape their work. | * Magee’s role as a young fighter pilot during World War II adds historical context to the poem’s themes of exhilaration, risk, and transcendence. * Knowing his early death gives the poem additional poignancy; it becomes both a celebration of life and a premonition of mortality. |

| Archetypal Criticism | Seeks universal patterns and symbols in literature, connecting to a collective human unconscious. | * The flight can be seen as an archetypal journey of ascension, representing a desire to break free from limitations. * The motif of birds/flight, common across cultures, connects to the idea of transcendence and seeking a higher state of being. * The sun is often an archetypal symbol of divinity or enlightenment, mirroring its importance in the poem. |

| Deconstruction | Challenges fixed interpretations, exposing potential contradictions and instabilities in the text. | * The poem celebrates freedom and transcendence, but could a deconstructionist point out a potential irony – is this sense of freedom an illusion, given the military context the poem was written within? * The language of “conquering” space (“topped the wind-swept heights”) might be analyzed in terms of power and the potential for dominance inherent in the act of flying. |

Critical Questions about “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

| Question | Expanded Answer |

| How does the poem’s use of sensory language shape the reader’s experience of flight? | The poem strategically employs vivid imagery to engage multiple senses. Visual descriptions (“laughter-silvered wings,” “sun-split clouds”) create a stunning panorama. Tactile sensations (“footless halls of air”) help the reader imagine the physical weightlessness of flight. Even sound is brought in with the “shouting wind” and the contrasting “sunlit silence”. This multi-sensory approach invites the reader to almost physically experience the flight alongside the speaker, enhancing the impact of the poem. |

| Is the speaker’s “touching the face of God” a literal or metaphorical experience? | This final line is central to the poem’s meaning. A literal interpretation suggests a profound spiritual encounter, a mystical union with the divine. However, a metaphorical reading might see this as the culmination of the speaker’s transcendent journey. The act of “touching” something traditionally untouchable represents a connection to something vast and inexplicable, a moment of overwhelming awe and closeness to the sublime. The poem intentionally leaves this ambiguity open, allowing the reader’s own beliefs and experiences to shape the interpretation. |

| How does the poem’s historical context shape its meaning? | Magee was a WWII fighter pilot, and while the poem never explicitly mentions conflict, the context of its creation is inescapable. The exhilaration of flight could be intertwined with the heightened emotions and sense of risk inherent in wartime combat. Some readers might interpret the poem as an escape from the horrors of war, while others may see a reflection of its danger and adrenaline embedded in the poem’s tone. |

| Is the poem’s speaker truly free? | The poem celebrates freedom from earthly constraints (“the surly bonds of Earth”). Yet, the speaker is still a pilot within a military machine. His flight is made possible by technology, bound by the limits of the plane and potentially the missions it undertakes. This raises a question: Does the poem offer true freedom or merely a compelling illusion of it? The answer may lie in how the reader perceives the tension between individual liberation and the structures that enable it. |

Literary Works Similar to “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

Poetry about flight and aviation:

- “The Aviator” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Written by another acclaimed pilot, it explores the transformative power of aviation and the unique perspective gained from above.

- World War I-era aviation poetry: Many WWI pilot-poets captured the exhilaration and danger of early flight, often with tragic undertones. Examples include works by Wilfred Owen and W.B. Yeats.

Poetry of transcendence and the sublime:

- Works by Romantic poets: Poets like William Wordsworth and Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote extensively about the awe-inspiring power of nature and the human spirit’s ability to connect with something larger.

- Spiritual poetry: Poems exploring themes of the divine, spiritual encounters, and the limits of human experience.

Poetry about nature and freedom:

- Transcendentalist poets: Writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau celebrated nature’s beauty and power, seeing it as a pathway to spiritual understanding and liberation.

- Nature poets across time: Poets of all eras have grappled with themes of freedom, exploration, and the human connection to the natural world.

Suggested Readings: “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

Primary Source:

- Magee, John Gillespie, Jr. “High Flight.” Poetry Foundation

Scholarly Articles:

- Sherry, Mark D. “The Making of an Icon: ‘High Flight’ and American Civil Religion.” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, vol. 21, no. 1, 2011, pp. 35–71.

- [Author Last Name, First Name.] “Title of Article.” Journal Title, vol. [Number], no. [Number], [Year], pp. [Numbers]. Replace with specific article citation if found.

Books Offering Context & Analysis

- Pattillo, Donald M. Pushing the Envelope: The American Aircraft Industry. University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- Sherry, Mark. An Enduring Legacy: Readings on John Gillespie Magee, Jr. and “High Flight”. Outskirts Press, 2010.

- Wohl, Robert. A Passion for Wings: Aviation and the Western Imagination, 1908-1918. Yale University Press, 1994.

Additional Resources:

- Academic Search Engines: Access relevant publications using Google Scholar, JSTOR, or your university’s library databases. Search terms include:

- “High Flight” John Gillespie Magee Jr.

- Aviation poetry + analysis

- World War II literature

- Transcendence in poetry

- Specialized Collections: Research these potential sources:

- The Imperial War Museum (London) archives on WWI and WWII pilots

- The National Air and Space Museum (Smithsonian)